“We are all students of Grisez now.” The man who said that several years ago was a Catholic theologian not generally seen as being a disciple of Germain Grisez. He was simply acknowledging the influence Grisez had already had on serious students of moral thought—an influence that, one might add following Grisez’s death, seems likely to continue growing for a long time to come.

Grisez, a cherished friend with whom I was privileged to collaborate in writing several books, once gave me a striking indication of that. Interviewing him for a profile I was writing, I asked whether he could point to any impact he’d had on the thinking of the pope of that day, John Paul II.

Yes, he said. He then cited the landmark 1993 encyclical on moral principles, Veritatis Splendor, where John Paul discusses human goods as fundamental principles of morality (something new in a document of the papal magisterium), and the encyclical’s treatment of the Beatitudes as embodying a vision of the moral life meant for all Christians without exception. Both things are major elements in Grisez’s moral theory.

He was born in Cleveland and studied there at John Carroll University, at the University of Chicago, where he received his doctorate in philosophy, and at the Dominican house of studies in River Forest, Ill., where he pursued his interest in the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas. He taught at Georgetown University, Campion College in Regina, Saskatchewan, and, for 30 years before retiring in 2009, at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Emmitsburg, Md. He died February 1 at the age of 88.

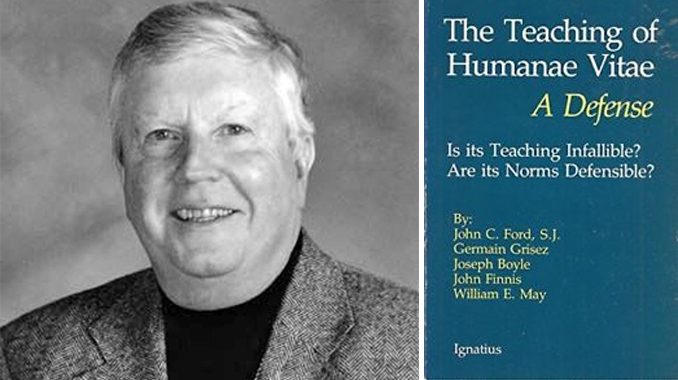

In the preceding half-century he’d produced a stream of notable articles and books. Among the latter is a work that constitutes a virtual Summa of moral theology—The Way of the Lord Jesus, whose three volumes, published between 1983 and 1997, and totaling nearly 3,000 pages, contain the definitive statement of his thought. He also was co-founder, with John Finnis of Oxford University and Notre Dame, of a new school of moral thinking generally referred to as the New Natural Law Theory.

Grisez was intensely loyal to the teaching of the Church. But that very loyalty, he believed, obliged him to critique arguments he considered inadequate sometimes put forward in defense of the teaching, and then to provide other, better arguments of his own.

This he conscientiously attempted to do, starting with his first book, Contraception and the Natural Law. Published in late 1964, over three years before Pope Paul VI’s encyclical Humanae Vitae with its condemnation of contraception, the volume defends Church teaching against artificial birth control while expounding a new approach to moral reasoning that centers on respect for human goods.

Much of Grisez’s contribution can be found in his books and articles on subjects like abortion, euthanasia, nuclear deterrence, and personal vocation. But his influence also was exerted quietly. That included preparing, at the request of a cardinal, a detailed critique of a draft of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. The cardinal submitted Grisez’s voluminous comments to the CCC’s drafters. The result was a catechism significantly stronger and clearer than it otherwise might have been.

He was buried in a hillside cemetery in Emmitsburg, close to his wife, Jeannette, to whom he was intensely devoted, and to one of their four sons, Joseph, who died young. The cemetery is not far from the seminary where, along with teaching seminarians, he wrote the works that, as my theologian friend remarked, make all of us “students of Grisez now.”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

If Mr. Shaw is monitoring this, does he know how the second and post widowed marriage of Grisez was resolved. Years ago on his website it seemed that they agreed to permanently separate and I don’t see how that is one option for Catholics.

Germain Grisez was certainly a faithful Catholic seeking to defend the faith on moral issues. What I have serious issue with is his argument along with Finnis and Boyle that it was permissible for the infant trapped in the birth canal to have it’s cranium crushed and removed. Their thesis was that the procedure was intended to modify the skull. Intent cannot make an evil act good. The object of the act is to crush the skull with forceps, which is to permanently maim or kill. “Finnis, for example, maintains that a doctor who performs a craniotomy to save the mother’s life does not intend to kill the baby (480-5). Now, it is true that the doctor’s project is not to kill the child, but to preserve the mother’s life. Nonetheless, it strains credulity to say that when the doctor crushes the child’s skull, she does not intend the child’s death. Surely, if the doctor crushes the baby’s skull knowing the baby will die, she kills the baby to save the mother” (John Keown and Robert P. George eds., Reason, Morality, and Law: The Philosophy of John Finnis, Oxford University Press). Germain was also a strict casuist. He developed a system of moral behavior that he presumed “covered every possibility”. Aquinas had the correct approach, which is to deliberate the conditions of the act. There are infinitesimal variables in many moral acts particularly regarding medical ethics.

A follow up on alternatives to obstructive labor is caesarean section the first option recommended by physicians Carmen Dolea MD and Carla AbouZahr MD to the World Health Organization Geneva 2003. The second was the abortive use of forceps. I’ve interviewed physicians who agree it’s a viable option.

But they don’t intend to kill the child because IF it were possible to then reassemble the skull after the removal (which someday it will be with enough technology)…these doctors would surely do so. They want the child to live. Its death is neither an end nor a means to their moral proposal. Rather, it is a side effect of a means (“changing the shape of the skull”) that is proportionate in this case to saving another life when otherwise both might die. There is nothing about the child *dying* specifically that is part of the direct causal chain here, and indeed if the baby somehow survived everyone would celebrate it.