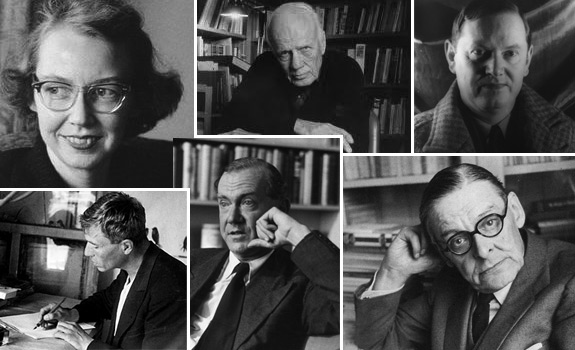

Some writers have a talent for composing stories or poems that contrast a yearning for truth and meaning with glimpses of the underbelly of human nature, often grim and raw stories that can give one the sense of peering into a rat hole. Authors like Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, Flannery O’Connor, Walker Percy, Boris Pasternak wrote in the vein, as did the poet T.S. Eliot.

Cowardice, equivocation, avarice, lust, vanity, betrayal; disorders and sins that today are psychoses to be treated or identities to be embraced. These aren’t easy stories and poems to read, so why bother?

One can say that many of the characters in these stories, or voices in these poems, for all their disorder and myopia, are seekers, discontented with a meaningless world. They are the prodigal son who may never return to his father’s house, the good thief who may not call out to his unjustly convicted cross-mate, the woman at the well who may walk away from the provocative rabbi, the tax collector impressed by the teacher but reticent to sacrifice his livelihood. There is always the possibility that these will succumb to cynicism or pride or avarice, and shove off.

Scary, but how many have we known, how many of us have been, at this crossroads, this precipice, this “what’s next?”

Carl E. Olson has written that Walker Percy’s first novel, “The Moviegoer is very much about the modern malaise; in fact, Percy wrote a brilliant essay, ‘Diagnosing the Modern Malaise’, which is in his collection, Signposts In a Strange Land, one of my favorite books. Percy, in short, believed that modern novelists had the task of diagnosing, not providing handy answers.” There are no “handy answers” in The Moviegoer, where characters ostensibly search for purpose and meaning, but only within prescribed limits, producing frustration and lost-ness. Similarly, Evelyn Waugh’s Tony Last in A Handful of Dust, experiencing many miseries, embarks on a seeker’s quest, but in a dead-end direction. Graham Greene’s Scobie (The Heart of The Matter), though a “rational” believer, is too circumscribed by a disordered sense of pity and justice to admit a Divine Mercy that restores broken man.

What separates these harsh voices from postmodern literature? The Waugh-Greene-O’Connor-Percy camp weren’t materialists or nihilists; that is, they were not writing from a perspective that life is devoid of transcendent meaning or purpose. To varying degrees, and working in different genres, Eliot, Pasternak, and the rest were searchers, questers, pleaders for that which “my heart is restless.” Were these writers conscious of this perspective as they plied their craft? Were they encouraging readers to ask the big questions? Were they confronting us with T. Rex and provoking us to question whether this is an utterly utilitarian, Darwinian, materialistic world…eat or be eaten, and then we die?

Eliot’s “Hollow Men” captures this nihilistic perspective:

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

Our rats’ feet over broken glass

In our dry cellar

Some contend that not all modern writers are nihilists, that many are scientific humanists, non-believers, but motivated by a humanistic ethos, devoid of a transcendent perspective, yet grounded in the welfare of man, or safeguarding the natural world in which man is an actor. When asked why he would exclude scientific humanism as a rational and honorable perspective, Percy said, “It’s not good enough. This life is too much trouble, far too strange, to arrive at the end of it and then to be asked what you make of it and have to answer ‘Scientific humanism’. That won’t do. A poor show. Life is a mystery, love is a delight. Therefore I take it as axiomatic that one should settle for nothing less than the infinite mystery and the infinite delight, i.e., God. In fact I demand it. I refuse to settle for anything less.”

The Walker Percy quoted above is hard to reconcile with the narrative voice in The Moviegoer. The same could be said of O’Connor and Wise Blood and Eliot and “The Waste Land”. Perhaps the underbelly of human nature is revealed so graphically in these stories and poems as a contrast to Augustine’s prayer, “My heart is restless and it shall not rest until it rests in Thee.” O’Connor’s Hazel Motes twists this restlessness into militant rebellion against his disordered image of Jesus, striving to found a church where “the deaf don’t hear, the blind don’t see, the lame don’t walk, the dumb don’t talk, and the dead stay that way”. Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago explores the meaning of freedom through the struggle of a fundamentally noble man with the external tyrannies of Czarist Russia and the Bolsheviks; also through the contradictions between Zhivago’s beliefs and actions.

These harsh voices plumb the gift of human freedom, and the burden of human freedom, but the last word is Divine Mercy, wherein we may hope, even in our abuse of freedom. J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings is a school of mercy, though Tolkien would hardly be placed in the Waugh-Greene-Percy camp of writers. Gandalf, an angelic being in Tolkien’s mythology, demonstrates mercy toward many makers of mischief, including Gollum, Saruman, and Denethor. To Frodo, who insists that Gollum deserves death, Gandalf replies, “Deserves it! I daresay he does. Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them? Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgment. For even the very wise cannot see all ends.”

(Editor’s note: This essay was originally posted on CWR on September 3, 2013.)

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.