The name of Dietrich von Hildebrand is known to many Catholics as a great writer, thinker, and teacher who influenced many people, both in America where he taught for decades and in his native Europe. But until I read My Battle against Hitler: Faith, Truth, and Defiance in the Shadow of the Third Reich I knew nothing of his early life except that he was a refugee from the Nazis.

What a fascinating story it is—and how excellent that we can now read it in his own words and, especially with the hindsight of history—ponder its significance.

The von Hildebrand diaries, as collated and published in this edition, begin shortly after the end of the First World War, when the young academic from Germany visited France, taking part in a conference organised by a French Catholic academic as part of a peace initiative. This was no bland let’s-all-make-peace-together assembly with people talking in cliches, but a tough commitment to finding a way forward in a continent where it was all too clear that future conflicts were quite likely.

And the French bishops weren’t happy with this kind of lay activity. Conservative and royalist, still insistent that the only right way ahead was to insist that the French monarchy be restored and remaining distant from other social and political realities, they were able, under the guise of trying to crush Modernism, to insist that all Catholic activity be under their specific control and subject to their ideological stance. Anti-semitism was also strong in French Catholic circles at that time, finding a voice in “Action francais”—later to be censured but at that time active and influential.

But it was to be German ultra-nationalism that caused the great problems for von Hildebrand, then and, of course, later. At the French conference he stated, as a Catholic, his opposition to the German invasion of Belgium, which had caused so much suffering in World War I, and found on arrival home that his words, distorted and robbed of their original context, were used to denounce him and mark him as a dangerous figure.

Over the next few years, the issues of anti-Semitism (especially among Catholics) and passionate nationalism central in Germany. In the murderous atmosphere of post-war confusion, assassination and violence stalked the country. And many in the Church seemed not to mind. After one such murder a priest said to von Hildebrand: “This won’t stir up the people. They’ll say ‘One Jew more or less is of no consequence’”.Von Hildebrand records his dismay at this moral blindness, and also the aching sense of the near-impossibility of changing such horrible attitudes.

There were sane voices, and it was still possible to work and plan for a better way ahead. But National Socialism gripped many; it is especially distressing to see how anti-Jewish attitudes framed so much of Catholic thinking at the time. One voice of courage and sanity was Cardinal Pacelli—later Pius XII—who became a friend of von Hildebrand (and as pope would save many Jewish lives during the Second World War).

Eventually having to flee Germany, von Hildebrand and his family settled in Vienna; there, a warm friendship with Dolfuss developed and funding became available for an anti-Nazi publication aimed at celebrating the best of the Austrian Christian social and political tradition. These chapters of the diary are full of hope—the old Habsburg lands offering some potential unity and goodwill across central Europe, and the Catholic faith sparkling with vision. The pages are filled with the names of men and women who not only recognised National Socialism as wrong but sought real alternatives. As we now know, it was not to be and the horrors, from Dolfuss’ murder to the increasing drumbeats of war in Germany, grew steadily.

It’s depressing, but it’s also a vivid description of an era that shaped our own, and it’s important that we understand its realities and its tensions. The Church learns from history; Nostra Aetate was born from the recognition of the wickedness of anti-Jewish attitudes that had developed and become standard among too many Catholics. St. Pope John Paul II would open up and transform the way Catholics understood lay action, offering a wide and hopeful vision echoing so much of the message that rings through von Hildebrand’s own work.

We need this perspective. In my early adult life I heard many voices telling me that the Second Vatican Council was a terrible mistake, and that in the “good old days” things were so much better in the Church. Wiser voices spoke of the value, authority, and importance of the Council’s teachings, but today, alas, a new generation is hearing siren voices under the guise of “Catholic Tradition”, and even anti-Jewish messages sweep around the Internet. Von Hildebrand’s diaries are important, even more important than he could have known when he was writing them.

This is a book that makes a gripping read, ending as it does with his escape from Vienna with his family; it is beautifully produced with useful footnotes and appendices. It is an important addition to Catholic intellectual life, and one that will stay with you.

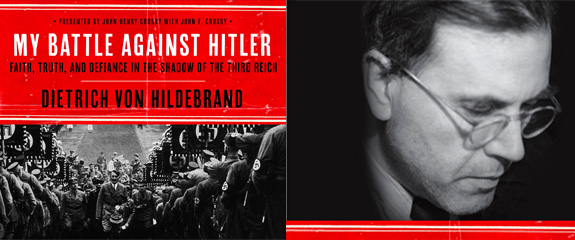

My Battle against Hitler: Faith, Truth, and Defiance in the Shadow of the Third Reich

by Dietrich von Hildebrand

Translated by John Henry Crosby and John T. Crosby

Image Book, 2014

Hardcover, 352 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.