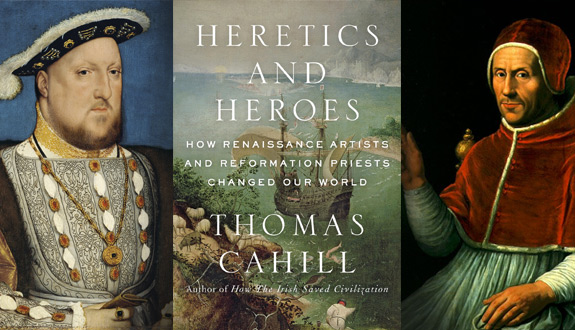

Since publishing the amusing How the Irish Saved Civilization in 1995, best-selling author Thomas Cahill has added five further volumes to his history of the West, the Hinges of History series. The latest volume, Heretics and Heroes: How Renaissance Artists and Reformation Priests Changed Our World, contains Cahill’s take on the great European intellectual, cultural, and religious movements of the period now commonly referred to by historians as “early modern”. According to the author, this series aims to “retell the story of the Western world as the story of the great gift-givers, those who entrusted to our keeping one or another of the singular treasures that make up the patrimony of the West.” Such “gift-givers” left behind “a world more varied and complex, more awesome and delightful, more beautiful and strong” than the one they had entered.

“We normally,” Cahill states, “think of history as one catastrophe after another, war followed by war, outrage by outrage—almost as if history were nothing more than all the narratives of human pain, assembled in sequence.” The Hinges series, however, is dedicated to “narratives of grace, the recountings of those blessed and inexplicable moments when someone did something for someone else, saved a life, bestowed a gift, gave something beyond what was required by circumstance.”

It seems we are in for a newer, gentler, kinder history of the West.

Outrage-free history?

And yet Cahill’s approach, as advertised, is not all that novel. Hear how an earlier writer distanced himself from conventional historians with their predilection for bloodshed and brutality: “Other historians record the victories of war and trophies won from enemies, the skill of generals, and the manly bravery of soldiers, defiled with blood and with innumerable slaughters for the sake of [their] children and country and other possessions. But our narrative of the government of God will record . . . the most peaceful wars waged in behalf of the peace of the soul, and will tell of men doing brave deeds for truth rather than country, and for piety rather than dearest friends.”1 As the Father of Church History, Eusebius of Caesarea, penned those words in the first half of the fourth century it can be seen that Cahill is, at least in aspiration, in good, and rather well-worn, company.

Outrage-free history, however, has never been easy to write. Eusebius never meant his annals to exclude human suffering or uncomfortable reading, as his ample reproduction of the acta of early martyrs testifies. And Cahill, though he professes that his goal is to focus on the inspiring aspects of the Renaissance and the Reformation, can hardly be said to gloss over the catastrophes and outrages of early modern history.

Moreover, he cannot in the end resist a good scandal, especially a good clerical scandal. In fact, Cahill’s accounts of important historical figures often reveals a decided tendency to deflate, to highlight not gifts, but rather foibles, faults, and failings (see, for instance, his treatment of John Calvin, 268-70, or of Ignatius Loyola, 242-43). The reader sometimes wonders if the volume might have been more accurately titled Heroes, Heretics, and Hypocrites.We do not learn, for example, only about Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s great sculpture and architecture, but must hear also that his daily Mass attendance and frequenting of Jesuit churches left him still a “highly competitive, high-pressured, vindictive son of a bitch” (125).2

We must not imagine, in another case, that Henry VIII’s marital futility and murders have been sufficiently covered by the old “normal” histories—no, we are treated here to the details of the “aging, gorging athlete” who was so fat near the end that the royal corpus could be moved only by machinery. We even get details of the supposed post-mortem explosion of Henry’s cadaver, bursting the coffin and “dripping putrid fat everywhere” (230). Many scholars opt to leave this legend out of their biographies of Henry VIII as lacking adequate documentation, but Cahill, as we know, is all about “the blessed and inexplicable moments.”

The Renaissance popes, of course, provide the most obvious fodder for a historian in search of this peculiar kind of inspiration. We get the nepotist Sixtus IV, implicated in the murderous Pazzi Conspiracy in 1478. We also get his successor Innocent VIII, “just a little worse” (75).3 And of course we get Alexander VI, “the worst pope in history” (53), and the Medici popes (147-49, 275). Julius II is highlighted, not simply because he was the pope responsible for dragooning Michelangelo into leaving posterity the great gift of the Sistine chapel, but also because of his scandalous ego and belligerence (116-120).

Of course, it’s foolish to imagine there could be a competent history of the Renaissance and Reformation that neglects the shameful delinquencies and crimes of the era’s bad popes. But a historian truly intent on highlighting the glimmers of hope for the future in the dark and gruesome past, might at least note the only Dutch pope in history, Adrian Florenzoon Boeyens, who as Adrian VI explicitly acknowledged that the fountainhead of the corruption in the Church was the Roman Court itself and aimed to reform the contemporary system of indulgences that had been the original catalyst for Luther’s protest. Unpopular in Rome and obstructed at every pass by a recalcitrant papal bureaucracy, Adrian might have accomplished more if he had not died in 1523 after a papacy of only twenty months. One non-scandalous pontiff in the wearying succession of papal delinquents, if only as an example that makes papal history “more varied and complex,” might have gotten at least a glance from a historian who trumpets his intention of eschewing the outrages and catastrophes favored by other historians.4

Mixed Renaissance fare

Of course, if we wanted nothing but gift-giving and inspirational stories we’d be reading Guideposts, not the history of this human world. Cahill writes engagingly and is at his best in his treatment of Renaissance art. The book is masterfully illustrated, featuring nearly thirty superb color plates and numerous quality black and white illustrations. He makes sure not to lose the art of the northern Renaissance—Holbein, Dürer, Brueghel, and Rembrandt—among all the great Italians. He even gives wise advice about how best to see the Sistine Chapel (118). The style is lively and allusions to contemporary celebrities and episodes abound.

On the other hand, in his efforts to keep his narrative popular and accessible, historical events and, especially, motivations are often grossly over-simplified. For example, the conspiracy to put Lady Jane Grey on the English throne in 1553 is summarized as “some bizarre high jinks” (276). The Spanish Armada is explained as a mere matter of Spain’s Philip II deciding that he should rule England instead of Elizabeth (279). The intra-confessional murderousness of the Reformation boils down to authorities taking “sadistic delight” in killing dissenters (265). Complex historical events are sometimes rendered so simplistically as to appear almost silly.

Cahill’s treatment of other aspects of the Renaissance is less sure-footed than his commentary on the art of the period. For example, Petrarch was in minor orders but never a priest (70). More importantly, his section on Renaissance humanists—“Humanists Rampant 1345-1498”—suggests that humanism was in decline in 1498. Stuck in an older historiography that viewed the Renaissance as inherently pagan, Cahill downplays the religion of the humanists as “often more formal than deeply felt.” Even more strangely, Cahill asserts that this evaluation of the religion of the humanists was the case “certainly by the end of the fifteenth century” (72), precisely the time that northern humanism, especially, was taking on an even more explicitly Christian hue in such representatives as Erasmus, John Fisher, and Thomas More.5

Lacking an explanation

But over-simplifications and reliance upon older scholarship aside, the main problem with the book is its neglect of its advertised task, i.e., explaining “How Renaissance Artists and Reformation Priests Changed Our World.” Heretics and Heroes, at length, is essentially a search through history for characters presenting features that appear “modern” to the searcher. He then provides lively biographical vignettes that emphasize these features, and (as it were) announces—“Voila, modernity in the Renaissance (or Reformation).”

But simply identifying new trends and developments in art and religion in the early modern period is not the same as explaining how modernity came to be. Emblematic for the whole work may be Cahill’s account of the Peace of Augsburg in 1555, when it was momentously resolved that each prince in the Empire could decide his own domain’s religion (cujus regio, ejus religio)—Cahill snappily explains, “And so it became” (262). And apparently that is that. Readers wishing some sustained argument about the gestation of the modern world will be disappointed.6

In the end, Heretics and Heroes is not an attempt to understand, or explain, the past from the perspective of the people of the past. It is a history of progress towards us, or, rather, towards those of us who are truly modern, in the right way. It is a peculiar kind of hagiographical enterprise—the scouring of history to find the people that are most like us. In fact, in his final chapter Cahill apologizes that, notwithstanding his good intentions, he has produced so many pages about “know-it-alls . . . prescribers and proscribers,” the “excluders” and limiters, “who want their circle—the circle of the saved—to be exclusive, as small and as (uncomfortably) intimate as possible.”

Cahill’s goal, his prescription (if I may), is inclusion: “opening one’s arms to everything and everyone,” as Gandhi advised, or Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount (291-92).7 And, as a culmination to his history, Cahill provides a few examples of modern “figures of hope” who lived this ideal (306). One of these, Pope John XXIII, gives the author an opportunity to revisit the subject of his own biography of the pope published in 2002.8 In both these works, so far from embracing everyone, Cahill does not seem able to make Good Pope John shine without scolding others. Predecessor Pope Pius XII was a “know-it-all control freak,” and John’s successors, especially John Paul II, are guilty of masterminding a “massive retreat from his [John’s] stance of open embrace.”9 Cahill reports the fears of a Jesuit friend that the Church would take two hundred years to “recover” from the Polish pope’s pontificate (308-09). And at the end of his John XXIII, as he anticipated John Paul’s death, Cahill allowed himself some remarkable predictions: “The conservatives will surely end up backing a cardinal from Latin America. John Paul has made his most reactionary appointments in this part of the world. . . . The choice of a Western European—say, an Italian or a German—will almost certainly signal a liberal victory.”10

Here there are lessons for historians, I suppose, about both hysteria and hubris, and subsequent events reveal more levels of irony than I can quite plumb. Perhaps nowhere has the irony been more dramatically evident than in April at the Vatican when a Latin American pope that Cahill would surely not call “conservative” (to use the simplistic label),11 in the presence of a retired German pope whom Cahill used to call “Grand Inquisitor,”12 raised to the altars John XXIII and John Paul II together, in a open embrace of them both, in seeming defiance of those who would prefer to limit the circle of celebration to only those they favor, and exclude the others. I hardly imagine that this is the kind of inclusion that Cahill demands, but if you can’t embrace even two, then calls for embracing everyone seem rather empty.

Heretics and Heroes: How Renaissance Artists and Reformation Priests Changed Our World

by Thomas Cahill

Doubleday, 2013

Hardcover, 341 pages

ENDNOTES:

1 Eusebius of Caesarea, Church History, Book 5, Introduction: 3-4, emphasis added.

2 One is reminded of Evelyn Waugh’s famous non-excuse for his inveterate rudeness: “You have no idea how much nastier I would be if I was not a Catholic. Without supernatural aid I would hardly be a human being.”

3 Even though commenting on Innocent VIII’s bastards (52) a historian sincerely interested in avoiding “outrage upon outrage” could have made clear that the offspring in question were born before Giovanni Battista Cibo took major orders. It is likely that evidence would demonstrate similar gratuitous exaggeration in Cahill’s assertion that popes continued “to sire bastards” for “several decades” after the closing of Trent (272).

4 There are also surprising missed opportunities in Cahill’s treatment of the heroes of the Reformation. He might, for example, have more amply introduced his audience to Martin Bucer, the irenic reformer of Strasbourg whose untiring efforts to make peace among the splitting Protestant churches earn him recognition today as a pioneer of ecumenism.

5 Those seeking a more refined understanding of Renaissance humanists and faith might consult Alison Knowles Frasier’s Possible Lives: Authors and Saints in Renaissance Italy (Columbia, 2005) or David Collins, S.J.’s Reforming Saints: Saints’ Lives and Their Authors in Germany, 1470-1530 (Oxford, 2008).

6 For a fuller, intellectually challenging treatment of this question, readers might try Brad Gregory’s The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society (2012).

7 Cahill’s Sermon on the Mount apparently lacks prescriptions and proscriptions, and is clearly innocent of any anxieties about lust or divorce.

8 Thomas Cahill, Pope John XXIII, in the Penguin Lives series.

9 To construct John XXIII’s reputation as the Pope of Anything Goes, of course, requires the overlooking of a great deal in John’s life and pontificate, for instance, his first encyclical Ad Petri cathedram (1959), which Cahill nowhere mentions.

10 John XXIII,233.

11 In an interview with Bill Moyer (December 27, 2013; accessed June 13, 2014), Cahill asserts that Pope Francis “doesn’t care” about doctrine or liturgy. I hardly think this kind of statement requires a response, but I wish somebody would tell these people that the category “doctrine” actually includes things of which they approve, like, say, certain aspects of Catholic teaching on Social Justice.

12 John XXIII, 226.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.