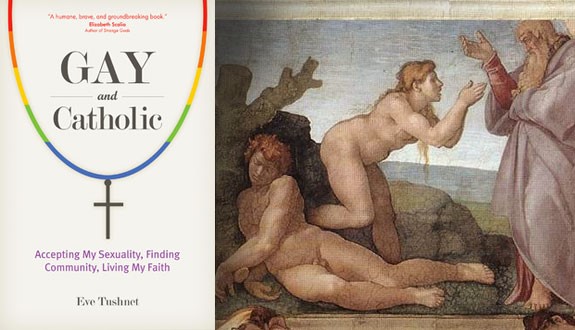

It is not without reluctance that I offer the following critique of Eve Tushnet’s Gay and Catholic: Accepting My Sexuality, Finding Community, Living My Faith (Ave Maria Press). My reluctance stems mainly from the conviction that her outreach to persons who experience same-sex attraction and to those who wish to better understand and love them is unquestionably motivated by Christian charity and a sincere intention to affirm and be faithful to the Church’s teaching on sexuality.

Tushnet’s Christian charity and compassion are evident throughout her book, and are clear from the three main ways she hopes to serve persons with same-sex attraction: “reduce…unnecessary suffering”; “indicate possible paths toward joy”; and suggest that “suffering does have meaning and can be offered to God.” Moreover, Tushnet agrees with the Church’s teaching on marriage and sexual morality: that marriage is the life-long union between a man and woman open to procreation, and that sexual union is morally permissible only within such a marriage.

Tushnet also advocates total sexual continence for those with exclusive or deep-seated attraction to persons of the same sex. Nevertheless, she rightly points out that continence should not be viewed in a primarily negative light—as if abstaining from sexual immorality is in the first instance a matter of saying “no,” rather than a matter of saying “yes” to God’s design for sex.

Our culture is, of course, increasingly intolerant and even hostile toward the Christian understanding of marriage and sexual morality. Thus, it takes courage to publicly affirm and defend these truths. This is perhaps especially the case when the person who is doing the affirming and the defending, at the same time, identifies herself as a “lesbian-gay-bisexual-queer-same-sex-attracted Christian.”

However, affirming the Church’s teaching on marriage and sexual morality is not necessarily synonymous with affirming the Church’s understanding of the human person and human sexuality. And if we lack a proper understanding of the latter, we will inevitably undermine the very truths about the former that we wish to affirm and defend. And this in spite of abundant good will and sincere intentions to the contrary.

It is just here—at the level of what John Paul II calls an “adequate anthropology”—that Tushnet’s work falls short and undermines her otherwise laudable project. Tushnet’s attempts to depict an understanding of human sexuality that is essentially grounded in LGBT gender theory as being compatible with the Church’s teaching on sexuality—and the fact that these efforts are quickly gaining popularity and acceptance in Catholic circles—call for a substantial and unwavering critique.

Tushnet fails to define what the Church’s teaching on sexuality is

In the first part of her book—in which she describes her childhood, adolescence, and eventual conversion to Catholicism as a college sophomore—Tushnet writes:

Instead of asking myself whether I understood the reasoning behind the Church’s teaching…I asked myself whether I was more sure that gay sex was morally neutral or more sure that the Catholic Church had the authority to teach sexual morality. And much to my surprise and dismay, I found that I was more sure of the second. I found that I was willing to accept the Church’s teaching even when I didn’t understand it. I began to prepare for Baptism.

Later she continues:

Over time, my understanding of what I was supposed to be doing as a queer Catholic changed radically. I began to see that the intellectual project was interesting and necessary, but I was probably not the right person to do it. … I no longer think that a major part of my work as a queer Catholic is illuminating the philosophical and theological underpinnings of the Church’s teachings on homosexuality.

Tushnet’s faith in the Church’s authority to teach sexual morality and her humility in recognizing her limitations with respect to understanding and illuminating the intellectual underpinnings of the Church’s teaching on sexuality are laudable; perhaps even reminiscent of Peter’s response to Jesus’ teaching on eating his flesh and drinking his blood (Jn 6:68-69). Nevertheless, it is highly problematic in a book that intends to affirm the Catholic teaching on sexuality and to advocate that others embrace and live by this teaching. Tushnet fails to define or even discuss what the Church’s teaching on sexuality is—let alone make the case for its truth and why it should be embraced as the path which leads to authentic happiness and human flourishing.

However, the chief issue here is not simply assessing whether an argument from authority is effective or ineffective. Some readers may find this approach persuasive and others may not. Rather, the main issue is that we don’t know what Tushnet means by the Church’s teaching on sexuality, and thus we don’t know what she is actually affirming and proposing for us to accept as the Church’s teaching on sexuality. In fact, she wants to “emphasize the diversity of ways Christians can understand our sexuality while remaining faithful.”

This becomes all the more problematic when we take into consideration the fact that she embraces an understanding of sexuality that has its roots in LGBT gender theory—that is, an understanding of the human person which recognizes as equally valid and true any number of sexualities and sexual orientations (heterosexual, gay, lesbian, queer, bisexual, transsexual, pansexual, asexual, etc.). Once a person has accepted the view that there is a “diversity of ways of understanding our sexuality while remaining faithful,” one has opened the door to LGBT gender theory. By adopting the “identities” of “gay” and “lesbian,” Tushnet is ontologizing same-sex attraction in direct contradiction of the Church’s understanding of the being of the human person as always and only male and female.

At best, then, Tushnet raises the question: is her understanding of sexuality in fact the same as the Church’s understanding, and is she therefore truly affirming and advocating the Church’s teaching on sexuality? At worst, she is—however unwittingly—misleading her readers into accepting an understanding of the human person and sexuality that is incompatible with the Church’s teaching and, thus, needs to be corrected and revised if she wishes to fully realize her intention to be faithful to that teaching.

The traditional Catholic understanding of the human person and human sexuality

The central tenet of the traditional Catholic understanding of the human person and human sexuality is that man—male and female—is created in the image of God (imago Dei). As Creator, God made a decision that the human person should always and only exist as a man or a woman. Consequently there are not multiple genders, as LGBT gender theory asserts, but only two: male and female. Our gender (or sex) is determined by the sex of our body: a person with a male body is a man and can never be otherwise; a person with a female body is a woman and can never be otherwise.

Thus, for example, when a person with a female body self-identifies as a man instead of a woman, this is not a sign that she is “transgender.” Rather, it is a sign that something has gone wrong with her psychosexual development. And the appropriate course of action for her is not to adopt a fictional gender, but to seek the healing of her psychosexual development so that she move towards accepting and embracing who she truly is: a woman.

Moreover, according to the traditional Catholic teaching on sexuality there are not multiple sexualities, as LGBT gender theory asserts, but only two: male sexuality and female sexuality. Consequently, there are only two sexual orientations. The sexuality of a man is oriented towards—is designed by God for—nuptial union with a woman. The sexuality of a woman is oriented towards—is designed by God for—nuptial union with a man. (As we will discuss later, the fact that certain men and women are called to celibacy for the kingdom does not entail the renunciation of their sexuality even as they are called to renounce the good of marriage.)

Thus when a woman, for example, experiences exclusive or predominant sexual attraction to women, this is not a sign that she has a lesbian orientation. Rather, this is a sign that something has gone wrong with her psychosexual development. And the appropriate course of action for her is not to adopt a false sexuality, but to seek the healing of her psychosexual development so that she can move toward accepting and embracing her true sexuality: a female sexuality that is oriented toward nuptial union with a man (without foreclosing the possibility of a call to celibacy for the kingdom which, again, does not entail the renunciation of her female sexuality).

Of course, due to our fallen state, some of us will not experience complete healing this side of heaven. Thus, the levels of healing that particular people experience will vary. It is true that some women who suffer gender identity disorder experience substantial healing of their psychosexual development such that their subjective experiences of who they are are brought into harmony with the objective truth of who they are. It is also true that others experience a lesser degree of healing such that they continue to experience some level of dissonance between their subjective experiences of who they are and the objective truth of who they are.

In a similar way, some women who suffer same-sex attraction experience substantial healing of their psychosexual development such that their subjective experiences of sexual attraction is ordered toward their true and proper end: a nuptial union with a man. Others, however, experience a lesser degree of healing such that their subjective experiences of sexual attraction remain more or less disordered: i.e., not ordered toward their true and proper end.

While some persons may never experience a complete healing of their gender identity disorder or their sexuality, self-identifying with a false gender or sexuality inevitably leads to unhealthy suffering. Embracing reality over illusion is often painful, yet this kind of pain is a healthy, even redemptive, suffering—one that ultimately leads to freedom and liberation. We can think here about Plato’s allegory of the cave. While leaving the shadows of the cave and walking into the bright light caused the slaves much pain, doing so allowed them to break the bonds of illusion and to enter the world of truth and reality.

When discussing why she doesn’t use the phrase “struggling with same-sex attraction” to describe her situation, Tushnet writes:

For other people, [the] language of internal division captures how they feel. They like the ability to think of their same-sex attraction as a consequence of the fall of man, not something inherent in their makeup. They think of it as something they can offer to God precisely because it isn’t an inseparable part of their nature.

While Tushnet doesn’t say that the above view is wrong, she reduces it to simply one option on a menu with others. Moreover, she says that one is free to reject this view (or “metaphor” as she calls it) if one does not find it helpful:

My point is that not everyone has the same spiritual needs I have…and therefore not everyone will be helped by the [same] language, metaphors, and corresponding self-understandings…. Therefore, when people reject one metaphor for their lives—whether the metaphor is being used to understand their sexuality, their addiction, or anything else—they shouldn’t be dismissed as in denial or resisting help. They may be expressing a genuine insight into their own spiritual needs and their own path to God.

The key here is that the understanding of same-sex attraction as a consequence of the fall and as therefore not something inherent to the nature of the human person is reduced to simply one metaphor among others. As a metaphor, it can be rejected in favor of others. Thus, one could, for example, adopt the view that same-sex attraction is not a consequence of the fall, that it is inherent to the nature of (at least some) human persons. The logical conclusion of this view is that same-sex attraction is a part of creation qua creation, it is one form of sexuality among others that God has created. And, while LGBT gender theory wouldn’t speak about creation or God creating different forms of sexuality, Tushnet’s view would seem to be something like LGBT gender theory + God.

According to the traditional Catholic teaching it is only by embracing the truth of God’s design for the human person and sexuality—even if that means going against the grain of our subjective self-understanding and our intensely felt sexual attractions—that we are set free to experience authentic peace and joy, even in the midst of great trials and suffering. Indeed, this is what the Catechism of the Catholic Church means by the virtue of chastity:

Sexuality affects all aspects of the human person in the unity of his body and soul. It especially concerns affectivity, the capacity to love and to procreate. … Everyone, man and woman, should acknowledge and accept his sexual identity. Physical, moral, and spiritual difference and complementarity are oriented toward the goods of marriage and the flourishing of family life. … Chastity means the successful integration of sexuality within the person and thus the inner unity of man in his bodily and spiritual being. Sexuality, in which man’s belonging to the bodily and biological world is expressed, becomes personal and truly human when it is integrated into the relationship of one person to another, in the complete and lifelong mutual gift of a man and a woman. (CCC, 2332, 2333, 2337)

It should be clear that Tushnet’s understanding of the Church’s teaching on sexuality is at odds with what the Church actually teaches on sexuality, even as she affirms the Church’s teaching on marriage and sexual morality. Moreover, she expresses deep ambivalence toward the Church’s official magisterial teaching regarding the objective disorder of exclusive or predominant sexual attraction to persons of the same sex.

In its “Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons,” the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith cautions us against an “overly benign interpretation” of the “homosexual condition” and renounces those who would go “so far as to call it neutral, or even good.” Tushnet describes this magisterial document in the following manner: “It includes certain official formulations that I find especially unilluminating. … This statement is not a jewel in the Church’s crown, I’m sorry to say.” Additionally, she seems to adopt throughout her book the very overly benign interpretation of same-sex attraction as neutral or even good that the Church expressly rejects. She writes, “I’m in no sense ex-gay. In fact, I seem to become more lesbian with time.”

Tushnet’s understanding of sexuality in light of John Paul II’s theological anthropology

The Catholic tradition has always viewed the human person as a body-soul union. Thus it rejects as false any dualistic anthropology that separates the body and soul—such as LGBT gender theory, which separates gender identity from the body and separates sexuality from the body. Nevertheless, the Church has tended to locate the imago Dei more or less in our spiritual faculties: i.e., in our intellect (self-consciousness) and our will (self-determination). This makes sense because God does not have a body; he is pure spirit. So, it stands to reason that we image God where we are most similar to him.

There is perhaps no person who better grasped and articulated the Church’s traditional teaching on the human person and sexuality better than St. John Paul II. Yet, his inclusion of sexuality—that is, the body in its sexual difference, in its masculinity and femininity—in the imago Dei marks a significant development in the Church’s theological anthropology. This development has not only profoundly enriched the Church’s understanding of the human person and sexuality, but has provided the Church a unique and effective voice for addressing the particular confusions concerning sexuality today.

According to John Paul II, sexuality is more than simply a biological reality; it is a sacramental reality as well: a visible sign of an invisible reality. The body—in its masculinity and femininity, in the dual-unity or fruitful unity-in-difference of man and woman—is a visible sign that points to the nuptial vocation of the human person. Human persons fulfill the deepest longings of their hearts and discover the purpose of their existence through communion—through a definitive and total gift of self in life-giving, fruitful love. Marriage is the first and paradigmatic communion of persons intended by the Creator, which is why John Paul II calls marriage the primordial sacrament.

John Paul II further explained that the nuptial meaning of the body doesn’t simply point to the communion of human persons. Rather, the body—when it is understood properly in its call to facilitate nuptial union—reveals, in some sense, the inner life of the Trinity, Christ’s spousal love for the Church, and the lofty vocation of the human person to participate in the Trinitarian exchange of love for all eternity.

Therefore, the human person is not simply imago Dei, but is more precisely imago Trinitatis. The conjugal union of husband and wife, which bears fruit in the transmission of a new human life, images the fruitful unity-in-difference of the three divine Persons: wherein, the eternal rhythm of total self-giving between the First and Second Person bears fruit in the eternal procession of the Third Person. This is why John Paul II describes the family as the icon of the Trinity. Moreover, the nuptial union of husband and wife reveals and images Christ’s nuptial love for the Church: on the cross, Christ (the Bridegroom) gives his bodily, total self-gift to the Church (the Bride)—and Christ’s nuptial union with the Church bears fruit in begetting the new life of grace (Baptism, Eucharist).

The nuptial vocation is, however, universal and not limited to those whose vocation is marriage. Those called to celibacy for the kingdom also possess a nuptial vocation, a definitive form of total self-gift that bears fruit in life-giving, fruitful love. While those called to the vocation of celibacy for the kingdom are called to renounce the good of marriage, they are not called to renounce the good of their sexuality.

A woman called to celibacy for the kingdom is no less a bride, wife, and mother than a woman called to marriage. She is called to a unique form of nuptial union with Christ, which is to bear fruit in bearing forth the life of the Spirit through spiritual motherhood. A man called to celibacy for the kingdom is no less a bridegroom, husband, and father than a man called to marriage. Through his unique identification with Christ as Bridegroom, he is called to a unique form of nuptial union with the Church, which is to bear fruit in generating the life of the Spirit through spiritual fatherhood.

In fact, as John Paul II has explained, the nuptial vocation of the man or woman called to celibacy for the kingdom has the unique mission to reveal our eternal destiny: nuptial union with the Trinity and nuptial union with one another in the communion of saints. In a real sense, then, the nuptial vocation of the celibate more closely resembles the definitive form of the nuptial vocation we are all called to in eternal life: “For in the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage” (Mt 22:30).

One of the great contributions of John Paul II’s theological anthropology is to show us that a proper understanding of the human person and sexuality leads to a proper understanding of our vocation and our destiny. Moreover, since our sexuality participates in our imaging of God, a proper understanding of the human person and sexuality leads us to a proper understanding of God. The converse, however, is also true. If we have a distorted understanding of the human person and sexuality, we will have a distorted understanding of our vocation and destiny. And, what’s more, we will have a distorted understanding of God.

To identify as a “lesbian-gay-bisexual-queer-same-sex-attracted Christian” is to distort the nuptial meaning of the body, and to distort the nuptial meaning of the body is to distort what the body is meant to reveal: our vocation, our destiny, and who God is. Perhaps, for example, this is why Tushnet—who describes her vocation as a celibate, lesbian-queer Catholic several times, but never describes her vocation as a celibate Catholic woman—supports the resurrection (in, it should be noted, a markedly different context) of vowed same-sex friendships for those who experience predominant or exclusive sexual attraction to persons of the same sex. Perhaps this is why she doesn’t seem to understand that the chief objection to such vowed, celibate same-sex couples is not on prudential grounds—as if the only problem would be that such an arrangement would provide an occasion of sin—but rather is that, in the case of a celibate woman, celibacy entails the renunciation of exclusivity with another person in favor of the exclusivity of nuptial union with Christ, which opens her to the spiritual motherhood of all Christ’s children. And, moreover, such a vowed, celibate lesbian would not have the capacity to image Christ’s nuptial love for the Church or the communion of Persons in the Trinity.

In any case, it should be clear that adopting an understanding of the human person and sexuality rooted in LGBTQ gender theory, as Tushnet does, is to reject the Church’s teaching on sexuality—however unwittingly and unintentionally. Therefore, while Tushnet does affirm the Church’s teaching on marriage and sexual morality, she nevertheless advocates a distorted understanding of sexuality which, again, inevitably leads to a distorted view of God, our vocation, and our destiny.

Tushnet’s book is not problematic because she lacks orthodox intentions, but because her undeniably orthodox intentions render her understanding of the human person, sexuality, and chastity—an understanding that, again, flows from LGBT gender theory—all the more credible. Thus, if Tushnet’s work is to bear the fruit she so genuinely desires, it seems to me that she may need to be open to revising her understanding of the human person, sexuality, and chastity in light of a substantial theological reflection, particularly one grounded in John Paul II’s theological anthropology.

Related Reading: “Gay, Catholic, and Called to Love”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.