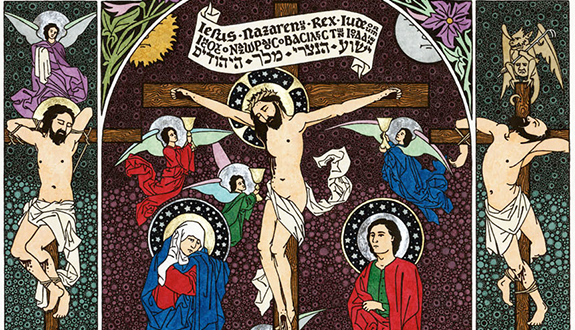

Daniel Mitsui (http://www.danielmitsui.com/) is a young artist who has, over the past dozen years, established himself as a unique talent, combining remarkable technical skills with a traditional vision of sacred art. In 2011 he was commissioned by the Vatican to illustrate a new edition of the Roman Pontifical, and the following year he established Millefleur Press, an imprint for publishing broadsides inspired by the work of 15th century printers. He recently corresponded with Carl E. Olson, editor of Catholic World Report, about his background, work, approach to sacred art, and his ambitious plan to “draw is an iconographic summary of the Old and New Testaments,” which will take some 14 years or so to complete.

CWR: You attended Dartmouth in the early 2000s, where you studied a wide range of mediums; is that where you decided to focus on on ink drawing on calfskin vellum, which you describe as your specialty? What attracted you to that medium, and what are some of its distinctive qualities?

Daniel Mitsui:I have been drawing primarily in ink since I was seventeen or eighteen years old. At first, I used very cheap materials—ballpoint pens and printer paper, which are not even archival. Despite their shortcomings, I was able to use them to make drawings that were precise and detailed. Precise, detailed artwork is what I have always liked and always tried to make.

When I went to college, I had in mind that I would become an oil painter, just because that seemed like the most prestigious medium. That was bad reasoning, and oil paint was something that I never learned to use properly. For a while I enjoyed making animated films, but the detail that I put into the drawings was wasted, as they could only be seen for a twenty-fourth of a second! Intaglio printmaking I enjoyed, as it is an exact medium; the reason I have not practiced it since leaving college is that it requires very expensive equipment and toxic chemicals.

Through my years of schooling, I made ink drawings on my own initiative; eventually I started using better pens and paper. This medium allowed me to use my particular abilities of concentration and manual precision to their best advantage. To me, specific materials and tools are not as interesting or important as the picture itself. I enjoy working with good materials and tools of course, but their purpose is to put in place, as exactly as possible, the picture I want to make.

It is for this reason that I now prefer to draw in ink with metal-tipped dip pens, on calfskin vellum. When used carefully, dip pens make the finest, most controlled lines. Calfskin is a very exact and forgiving surface for drawing. Paper is composed of randomly arranged vegetable fibers, but vellum is composed of organized layers of skin cells. The ink does not bleed much on it, and it is easy to scrape away the top layer cleanly with a knife. I use a knife almost as much as a pen—for making corrections, sharpening lines, or etching details into the ink. Goatskin is a fine drawing surface as well, but I prefer calfskin because it is thinner and translucent.

CWR: In 2004, the same year you finished at Dartmouth, you entered the Catholic Church. What was your background prior? What drew you to the Church? And how did that affect you as an artist?

Daniel Mitsui:My late father had been raised a Baptist, but did not profess any faith during the years of my childhood. My mother had been raised Catholic; my parents had married outside the Church. Our home did have a crucifix on the wall and a Bible on the shelf (some of which I read privately); for a while, my family attended Mass on Christmas and Easter and rarely on other Sundays. Although I was not baptized until I was an adult, I have believed Catholicism to be true for as long as I can remember. I do not have a natural explanation for that.

From early childhood, I remember an attraction to anything resembling medieval art: Lego castles, Eyvind Earle’s painted backgrounds to the Sleeping Beauty animated motion picture and Trina Schart Hyman’s illustrations to St. George and the Dragon were particular favorites. Obviously, these are not religious works, but the association between medieval art and the Catholic Church early formed in my mind. I remember as a young child being fascinated with the spires of gothic churches near the library where my mother worked, imagining what must be inside them. The first Gothic buildings that I saw from the inside were the chapels at the University of Chicago. I was perhaps fourteen; this made a very strong impression on me. About that same time, I encountered reproductions of illuminated manuscripts for the first time and was immediately fascinated, most especially by the Lindisfarne Gospels. I was deeply affected also by reading a translation of the Divine Comedy.

Perhaps it was best that my idea of the Catholic Church was formed more by medieval art and literature than by the typical parochial experience in the Chicago suburbs during the 1980s and 1990s! Had I been a more courageous child, I would have sought religious initiation on my own, or demanded it; instead, I determined to seek it after leaving my parents’ house. But during my first few years away at Dartmouth, I was depressed and resisted my religious desire. Eventually, I had to admit to myself that I could not remain indifferent so I contacted the priest on campus and went through the RCIA program at the student center. I was baptized and confirmed, and received my first communion, at the Easter Vigil in 2004, shortly before graduation.

At that time, I also determined to devote my creative effort to religious artwork; this represented not so much a change as a return. During the years when I was resisting my faith, I was most influenced by early comic strips and the surrealist art of Max Ernst; I realized that I liked these because of their affinity with illuminated manuscripts and the works of late medieval masters such as Hieronymus Bosch.

CWR: Much art today—whether visual, musical, or literary—seems preoccupied with personal experience and expressing one’s feelings, passions, desires. But you emphasize, in your site, that you are intent on being “faithful to the Second Nicene Council’s instruction that the composition of religious imagery is not the painter’s invention, but is approved by the law and tradition of the Catholic Church.” Why that particular approach? In what ways is it counter to the prevailing tastes of the larger “art world”?

Daniel Mitsui: The world has need for different sorts of art that are intended to do different things; indeed for different sorts of art made as an expression of religious faith. Some of those are very personal and singular, and great because of that. But there is a distinction between sacred art and secular art that is Catholic in its subject or motivation; the criterion of sacred art is that established by the Second Council of Nicaea.

Sacred art is always traditional. In its symbolism, it visually presents the exegetical method taught by Jesus Christ to the Apostles and elaborated by the Church Fathers. Its content and arrangement corroborate the liturgy, ultimately bearing witness to the same perpetuated memory of sacred events. Its presentation of space and time and light is philosophically correct. Discovering and continuing this tradition is to me very interesting, very satisfying.

Now it would be easy to misunderstand this requirement of tradition to mean that only a specific primitive style of art is truly sacred. I do not think that is correct either; sacred art must also glorify God through beauty as much as possible. I think these two requirements are nowhere met better or more harmoniously than in the art called Gothic, which emerged in the middle of the twelfth century.

Gothic art is a summary of the sacred art of the preceding ages, put into order and expressed more clearly. Yet it looks very different from early medieval art; it is refined and gorgeous in a way that early medieval art is not. I do not think of Gothic as a mere historic style characteristic of a certain time and place, but as the best example of art made according to Catholic principles that are enduringly true. This is why I make it the foundation of my own artwork.

CWR: In an address you gave in 2015 at the opening of exhibit of your work at Franciscan University of Steubenville you stated, “How beautiful that the Catholic Church celebrates the finding of things that have been lost, and the retaking of things that have been stolen. This seems especially relevant in our own age; at times I feel that most of my religion has been lost, or stolen from me.” What are some ways in which religion has been lost or stolen? In an increasingly secular and even anti-Christian age, what do you think the role of the Catholic artist should be?

Daniel Mitsui:We are living in a time comparable to the iconoclastic crises of the seventh and eighth centuries. A contempt for tradition, including artistic, is encountered at all levels of the Catholic Church. That is obvious enough.

An earlier, less recognized, damage was done to sacred art in the late sixteenth century. The brief and unspecific instructions of the Council of Trent for bishops to oversee sacred art within their dioceses were interpreted by some as permission to subject the entire tradition to critical judgment. The most thorough of these censors, John Molanus, was blind to the symbolic order in medieval art; he condemned and forbade every traditional composition that he did not understand, which amounts to nearly all of them. His writings were influential far beyond his own diocese. Through no fault of their own, religious artists working since the time of this censorship inherited of an impoverished iconography.

The meaning of traditional sacred art became obscure; medieval works that once catechized the unlettered now require written commentary to interpret. In such a time, I believe that those aspiring to make sacred art must be scholars and teachers as well as artists. They should know the work of archaeologists and iconologists who, since the late 19th century, have deciphered many traditional symbols and compositions; they should continue that work and make it popular. Visual expressions of theology, no matter how profound or beautiful, are ineffective if nobody understands them.

CWR: From your perspective as a working artist, what in general is the state of the visual arts within the Catholic Church in the U.S.? What can be done to encourage and help artists?

Daniel Mitsui: It’s unwell. One of the biggest problems is that the institutions of the Catholic Church, such as dioceses and parishes and seminaries, do not dependably defend tradition. Many bishops and priests are hostile to it, and even those that want traditional sacred art are worried about provoking rebellion from the faithful who do not. What emerges as a result is a kind of insipid, just-traditional-enough art that avoids causing offense only because it is easy to ignore.

I feel sorry for sacred artists who depend on institutional patronage. It seems that they expend most of their creative energy fighting for permission to make the best art possible. Art does not flourish under such conditions; to make the best art possible ought to be every artist’s job description. Although I would like to see more of my own artwork in churches, I am grateful that I am able to sell most of my drawings and prints to private individuals. This means that I do not need to fight these battles.

I encourage all aspiring sacred artists to take responsibility for their own formation and to make the most beautiful, most traditional art that they can without compromise. That, of course, would be easier if sound instruction were more widely available. I am trying to fill some of this need myself; I recently started a web log for writing about the principles and symbolism of sacred art, and the methods of making it. I offer there educational material for free download, including coloring sheets and activities for children.

CWR: What are some past projects and commissions that you’ve worked on?

Daniel Mitsui: I recently completed a drawing of the Tree of Jesse that included all of the ancestors mentioned in St. Matthew’s genealogy. To fit all of these figures in a coherent picture, I designed a framework of Gothic tracery through which the tree climbed, as if on a trellis. The combination of the orderly, geometric forms of the framework with the organic forms of branches, flowers, leaves and almonds was, I think, very effective.

My recent drawings of St. Hugh of Lincoln, St. Adelaide and Sarah the Matriarch were especially satisfying because I successfully used new methods for working on calfskin vellum: applying ink via sponges and decalcomania for natural textures, scratching details with a knifepoint, drawing on the reverse side to create ghostly images. The trees in their backgrounds I modeled on the artwork of Eyvind Earle, one of my earliest influences. Their ornament I based not only only Gothic, but also on Northumbro-Irish and Persian forms.

In 2015, I was challenged by one of my patrons to create a new, unsentimental image of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. I determined to reconnect this devotion to its early expressions in the visions of St. Gertrude, and to create an image with the vigor of late medieval art. This became one of my most popular drawings; I made several versions of it over the following years.

CWR: You recently revealed, on your site, an ambitious plan to “draw is an iconographic summary of the Old and New Testaments,” which will take about 14 years and will consist of 33 large drawings and another 165 or so smaller drawings. What inspired this decision? What else can you tell us about the project?

Daniel Mitsui: For years, I have wanted to draw longer series of pictures, consistent in style and size. Most especially, I have wanted to draw more of those subjects that are the very raw stuff of Christian belief and Christian art: the events of the Old and New Testaments. No other subjects offer an artist such opportunity for beauty and symbolism. Were I never to draw them, I would feel my artistic career incomplete.

The Summula Pictoria will be realized as 235 ink drawings on calfskin vellum. Forty large ones, about 9 inches square, will summarize the life of Jesus Christ. 124 smaller ones will summarize the Old Testament; 56 more in the smaller size will depict the lives of the Blessed Virgin Mary, John the Baptist and the Apostles. There will also be 13 iconic portraits of holy persons, and larger drawings of the Last Judgment and of the Tree of Jesse. The full list is on my website.

I plan to undertake this task in the spirit of a medieval encyclopedist, who gathers as much traditional wisdom as he can find and faithfully puts it into order. I want every detail of these pictures, whether great or small, to be thoroughly considered and significant. And I want to begin this task soon, so as to complete it in those years that I can be reasonably confident that my eyesight and manual dexterity will endure.

I plan to devote much of the next two years to research and planning, improving my technical skills and raising funds for the project. The pictures I plan to draw over twelve years, from Easter 2019 to Easter 2031.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply