The specter of child sexual abuse by priests still looms on the ecclesiastical landscape in Ireland. The findings of two government-sponsored judicial inquiries are due to be published later this year. Both reports are expected to highlight serious inadequacies in the hierarchy’s response to allegations of abuse dating back to the 1950s.

The specter of child sexual abuse by priests still looms on the ecclesiastical landscape in Ireland. The findings of two government-sponsored judicial inquiries are due to be published later this year. Both reports are expected to highlight serious inadequacies in the hierarchy’s response to allegations of abuse dating back to the 1950s.

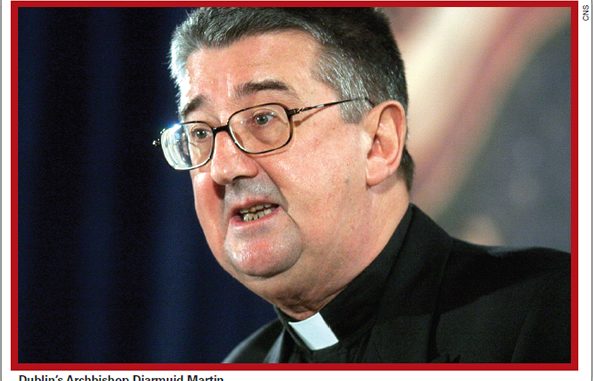

Dublin’s Archbishop Diarmuid Martin, a former Vatican diplomat parachuted into Ireland’s most populous diocese in 2003 at the height of public anger toward the Church, has been working to repair the damage. He has handed over almost 20,000 documents to the commission investigating historical allegations in his diocese over a 40-year period.

Archbishop Martin’s cooperation with the commission has not been without controversy. In January his predecessor, Cardinal Desmond Connell, successfully sought an interim injunction in the High Court to prevent the commission from examining some documents to which the cardinal believed he had legal privilege.

The immediate public reaction was one of outrage. “The cardinal is trying to cover things up,” one angry caller told a radio talk show. “They don’t want the truth to come out,” another caller fumed.

Cardinal Connell’s attempt to vindicate his legal rights turned into a public relations disaster for the Church. After an intervention by Ireland’s primate, Cardinal Sean Brady, Connell reluctantly dropped the challenge. The damage, however, was done.

The incident illustrated the debilitating effect the crisis has had on the Irish hierarchy and on Church morale in general. Another indication of this is the fact that late last year the National Conference of Priests in Ireland (NCPI), once a powerful voice within the Church, disbanded itself after no one came forward for election as president.

Father Bill Bermingham, a member of the committee that was set up to oversee the dissolution of the NCPI, said that while at a national level a lot of work had been done by the group’s executive, “there seemed to be a lack of connection between the NCPI and many priests throughout the country.”

Bishop Philip Boyce of the Raphoe diocese, who had been the bishops’ representative to the NCPI over recent years, said he was “saddened” to hear the news. Many priests do not share his sadness, however.

Paul Keenan, a religious affairs commentator based in Dublin, believes the dissolution of the priests’ conference points to a much deeper unease in the Church in Ireland. “There’s a lack of direction, there’s a sense everywhere in Ireland that the landscape for the Church has changed. No one, however, can put a finger on that change or where it will eventually lead the Church.”

LOST VOICE AND CLOUT

There’s no doubt that the fall-out from the clerical sexual abuse crisis has damaged the standing of the hierarchy immensely. From a once-powerful body that could topple governments in the 1950s, the Church’s leaders have effectively been reduced to offering occasional opinions on the shape of Irish society via press releases.

“The bishops are finding it hard to regain their voice,” says Seamus Mulconry, director of public affairs for the Irish office of Edelman, a global public relations firm. As a former policy adviser to politicians, Mulconry had frequent contact with the hierarchy. “It’s very hard now for the government or policy makers to find the Catholic voice; the bishops are certainly finding it difficult to speak out on issues of concern.”

Last year when a parliamentary committee published a report on the possibility of reducing the age of sexual consent from 17 to 16, a statement from the bishops expressed “amazement” that “politicians and public opinion makers shy away from confronting the basic demands of morality, namely what is right and wrong. Until such time as morality is respected for what it is—the bedrock of personal integrity and of communal life—Irish society, in the midst of increasing material prosperity, will continue its downward descent into moral chaos where literally anything goes.”

The statement was broadly welcomed by parents and other lobby groups. However, the Church attracted sharp criticism when news emerged that the bishops had not responded to a request for a submission from the parliamentary committee preparing the report.

Mulconry believes that there is a great openness to hearing the voice of the Church in the political sphere. But the structure of the Irish Bishops’ Conference has serious limitations.

The Catholic Communications Office, which is responsible for all the Irish Church’s media operations, runs on a skeletal staff of only four people. The other departments of the Church’s central administration are similarly under-staffed. While there are episcopal commissions that meet from time to time, there is no office dealing with marriage and family issues. There is no pro-life office, nor is there an office dealing with public affairs.

When a recent report from the Irish Council for Bioethics recommended embryo experimentation, a national newspaper contacted the bishops’ conference for a reaction and was told no comment would be forthcoming until such time as the report was read. There was no indication of when this would happen.

David Quinn, director of the Iona Institute, a socially conservative Irish think tank, told CWR: “Why the bishops need time to read the report before commenting on the specific recommendation concerning human embryos is, of course, anyone’s guess. At least we can assume with considerable certainty that they’re not open to persuasion on this point.”

Quinn, a former newspaper editor, said that “telling a journalist that there will be no comment until a given report is read is, in fact, a time-honored facesaving device used by all manner of organizations. What it really means is that the organization in question has either not given the issue enough thought to be able to make a meaningful comment, or else it has no one on hand able to give a quick response.”

Quinn insists that “the fact that the Catholic Church is so slow to respond when something arises that is threatening to a culture of life—such as embryo experimentation—or a culture of marriage— such as gay civil unions—leaves a huge hole in Irish public discourse.”

As is the case in many western nations, religious life in Ireland is also experiencing a crisis of identity. Most notable has been the transformation of superiors into administrators and the restructuring of the Conference of Major Religious Superiors—now known as the Conference of Religious in Ireland (CORI) —into what seems to be a parallel episcopal conference, including the setting up of “desks” to coordinate various tasks, ministries, or apostolates.

While the bishops’ conference has largely failed in recent years to have its voice heard in the media, CORI has managed to organize itself into an effective lobbying group. CORI is now a key partner in the so-called “partnership process,” a set of negotiations among government, employers, and trade unions aimed at fostering workers’ rights and wage restraint. Newspaper columnists frequently refer to CORI as “the only real opposition to the government.”

THE VOCATION CRISIS

Laudable as this is, the religious orders have, sadly, been less successful in attracting vocations to perpetuate their ministry. Female religious life has been particularly badly hit: while more than 300 religious sisters died in 2007, only three young women took perpetual vows. Many of the once-legendary religious orders that ran Ireland’s hospitals and educational infrastructure for 150 years have virtually vanished from the public sphere.

Of course, the impact of clerical sexual scandals on the public perception of Irish Catholicism cannot be overlooked. Many priests and religious feel unnerved and unable to contribute to important public debates. In stark contrast to their counterparts in Britain, Irish clerics rarely urge the faithful to lobby the government or encourage lay people to organize themselves politically. While recent focus groups found that some 25 percent of voters consider their faith very important in choosing whom to vote for, the Church has failed to mobilize this constituency.

There is no doubt that the position of the Catholic Church in Ireland has been bolstered by outgoing Taoiseach (Prime Minister) Bertie Ahern. Before he retired from office in May, Ahern established a “process of structured dialogue” where Church leaders could meet regularly with senior government ministers to discuss policy concerns. Ahern also stubbornly defended the relationship between Church and state. When one intemperate parliamentarian complained about “cozy phone calls between government buildings and Drumcondra [the home of the Catholic archbishop of Dublin],” Ahern responded angrily that he had “no intention” of changing his relationship with the Church.

But his successor, Brian Cowen, has kept silent on the relationship he believes ought to exist between the Church and the government. Pat Carey, Cowen’s chief whip—a kind of parliamentary enforcer in the Irish legislature— told CWR: “Faith and the values of the Church will continue to play a very important role in government policy. We are interested in the Church’s contribution, that won’t change.”

ROME’S RESPONSE

There are some indications that news of Ireland’s difficulties is being studied carefully in Rome. Seven out of the 10 recently appointed Irish bishops have come from overseas, Irishmen working for the Holy See or engaged in some function for the Church abroad. The overseas appointments may well bring fresh energy to the hierarchy. None of the recently appointed bishops were in Ireland at the height of the scandals, and thus none of them are tainted by those past failings.

New bishops, however, will be only part of any possible revival in the fortunes of Irish Catholicism. Ireland is experiencing a crisis in priestly vocations of epic proportion. In 2007, only nine young men were ordained to the priesthood to serve in Irish dioceses; in stark contrast, 200 priests died. With no sign of the vocations crisis abating, the number of priests will drop from some 4,752 priests currently serving to just over 1,500 priests by 2028.

As a means of addressing this dramatic fall, the Church is currently engaged in a “Year of Vocations.” It will be an uphill struggle, however; it will take more than an upbeat promotional campaign to breath wind into the sails of the Church in Ireland.

Father Oliver Rafferty, S.J., a Church historian based in Dublin, believes that the Church in Ireland is paying a high price for failing to grasp the reality that Ireland has changed over recent decades from a largely rural and agricultural economy to an industrialized one. “That failure was evident in the hierarchy’s lack of preparation for the Second Vatican Council,” he says. “Irish bishops scarcely made an impact in the council’s debates.”

When Dublin’s Archbishop John Charles McQuaid returned to Ireland following the council, he declared that nothing had happened at Vatican II “to disturb the tranquility of Irish Catholicism.” This, Father Rafferty believes, was “emblematic of the failure of Church leadership to deal with the profound changes taking place in Irish society in the 1960s.”

“At the opposite end of the spectrum there was a failure of nerve in the catechizing and acculturation of children to the practice of Catholicism. The instruction of children in religious matters became at times almost entirely separated from ideas of the content of the Christian faith and Catholic practice, so that teenagers matured into young adulthood without any clear and distinct idea of what it meant to be a Catholic,” Father Rafferty says.

Members of the so-called “catechetical establishment” in Ireland, inspired by such questionable sages as Father Thomas Groome of Boston College’s theology department, deflect any criticism of their approach by insisting that opponents are “ideologically motivated.” Along overdue National Directory on Catechetics has been delayed for almost two years now after many educators and parents complained about an earlier draft.

THE NEED FOR BOLD REFORM

Some commentators believe a tidal wave of reform is needed if there is to be renewal in the Irish Church. Father Vincent Twomey, a retired professor of moral theology at Ireland’s national seminary and a one-time student of Joseph Ratzinger, has been calling for reform starting with the restructuring of dioceses. Ireland currently has 26 dioceses, some with fewer than 30,000 Catholics. Father Twomey says, “There are simply too many dioceses in Ireland, and most of them are too small.”

Father Twomey cites the example of Austria, which is geographically slightly smaller than Ireland. With over six million Catholics, Austria has just 12 dioceses.

“For a country that has a Catholic population only three-quarters of that of Austria, Ireland has around three times the number of bishops serving twice as many dioceses,”

Father Twomey says. Father Twomey thinks that there ought to be fewer dioceses and, by extension, fewer members of the Irish Bishops’ Conference. “A smaller bishops’ conference should, for various obvious reasons, ensure more active participation by all members as well as greater cohesion and effectiveness as a national body.”

However, he also warned that a reshaped bishops’ conference “should not take away from the primacy of the individual bishop’s voice in the public forum.”

Many of Father Twomey’s suggestions, including a bold plan to revitalize religious life, have been met by the numbing force of traditional Irish style; namely, a dour and silent clinging to the status quo in the name of “realism” that is often mere failed pragmatism. Not one bishop has responded to Father Twomey’s call for reform, despite the fact that he first advanced his plans almost five years ago.

What the future of the Church in Ireland holds remains an open question. Those hoping for some sort of restoration of Ireland, “Gaelic, Catholic, and free,” will wait in vain. At the same time, those who are ready to glory in the demise of a discredited institution will view the secularist Ireland of the future with some horror. What is most likely is that the Church will continue, albeit in reduced circumstances, to influence the religious and cultural development of the Irish people, if only by virtue of the fact that Irish identity remains inextricably bound up with Catholicism.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.