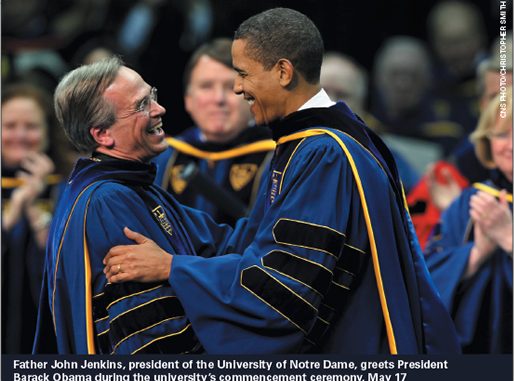

On May 17, Notre Dame conferred upon Barack Obama an honorary law degree even as the US president geared up to pass more laws that would violate fundamental moral teachings of the Church. Thunderous applause greeted Obama as he received from Father John Jenkins, Notre Dame’s embattled president, a degree that read in part:

On May 17, Notre Dame conferred upon Barack Obama an honorary law degree even as the US president geared up to pass more laws that would violate fundamental moral teachings of the Church. Thunderous applause greeted Obama as he received from Father John Jenkins, Notre Dame’s embattled president, a degree that read in part:

A community organizer who honed his advocacy for the poor, the marginalized and the worker in the streets of Chicago, he now organizes a larger community, bringing to the world a renewed American dedication to diplomacy and dialogue with all nations and religions committed to human rights and the global common good.

Through his willingness to engage with those who disagree with him and encourage people of faith to bring their beliefs to the public debate, he is inspiring this nation to heal its divisions of religion, culture, race, and politics in the audacious hope for a brighter tomorrow.

This is a dubious statement, to say the least, reflecting not official Church teaching but the left-wing political sensibility of Notre Dame officials and faculty. Obama joked after receiving it that he was “one for two” with respect to honorary degrees as president, though he failed to note the irony of receiving an honor from Catholic Notre Dame while being denied one a week earlier from secular Arizona State University (whose administration felt that he hadn’t been in office long enough to justify one).

Jenkins, in his enthusiastic introduction for Obama, perfunctorily mentioned that Notre Dame “opposes” Obama’s policies on abortion and embryonic stem cell research and omitted any mention of the president’s many other rejections of the natural moral law, from his support for same-sex civil unions to his support for euthanasia and condom promotion in high schools.

For all of Jenkins’ promises of positive but principled “engagement” with the president, he provided little of it, devoting most of his remarks to flattering and questionable descriptions of the president’s policies and to vapid restatements of the value of “differences” and “dialogue.”

The event at times resembled little more than a celebration of heterodox, “Seamless Garment”-style Catholicism.

Obama, picking up on the day’s tenor, used his commencement address to praise Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, the late archbishop of Chicago who coined the phrase “the Seamless Garment,” a concept that reduced abortion to just one of many “Catholic issues.”

Bernardin, explained Obama, had helped form his commitment to community organizing and his understanding of Christianity:

I found myself drawn—not just to work with the church, but to be in the church. It was through this service that I was brought to Christ. At the time, Cardinal Joseph Bernardin was the archbishop of Chicago. For those of you too young to have known him, he was a kind and good and wise man. A saintly man. I can still remember him speaking at one of the first organizing meetings I attended on the South Side. He stood as both a lighthouse and a crossroads—unafraid to speak his mind on moral issues ranging from poverty, AIDS, and abortion to the death penalty and nuclear war. And yet, he was congenial and gentle in his persuasion, always trying to bring people together; always trying to find common ground. Just before he died, a reporter asked Cardinal Bernardin about this approach to his ministry. And he said, “You can’t really get on with preaching the Gospel until you’ve touched minds and hearts.”

Obama also singled out for praise former Notre Dame president Father Theodore Hesburgh, who in 1967 spearheaded the “Land O’ Lakes Statement on the Nature of the Contemporary Catholic University,” a manifesto that laid the groundwork for Notre Dame’s secularization.

Obama, continuing his divide-andconquer strategy for the Catholic vote, exhorted Notre Dame graduates to follow the example of Bernardin and Hesburgh:

But as you leave here today, remember the lessons of Cardinal Bernardin, of Father Hesburgh, of movements for change both large and small. Remember that each of us, endowed with the dignity possessed by all children of God, has the grace to recognize ourselves in one another; to understand that we all seek the same love of family and the same fulfillment of a life welllived. Remember that in the end, we are all fishermen.

But as you leave here today, remember the lessons of Cardinal Bernardin, of Father Hesburgh, of movements for change both large and small. Remember that each of us, endowed with the dignity possessed by all children of God, has the grace to recognize ourselves in one another; to understand that we all seek the same love of family and the same fulfillment of a life welllived. Remember that in the end, we are all fishermen.

Obama is, if nothing else, an effective fisher for votes and his well-delivered platitudes and sophistries wowed the crowd. Only a few protests interrupted his speech. “Abortion is murder,” one protester chanted, according to press reports. Another said, “Blood is on your hands.” But these protests were quickly drowned out by a “We are Notre Dame” chant from graduates.

One of Obama’s adroit speaking techniques is to sound like he is making a concession to his opponents while in reality offering them nothing of substance—rhetorical sleight-of-hand on ample display in his speech to Notre Dame graduates.

To take one example: the “controversy surrounding my visit here,” he said, prompted him to remember “an email from a doctor who told me that while he voted for me in the [Democratic] primary, he had a serious concern that might prevent him from voting for me in the general election.” The doctor, “who described himself as a Christian who was strongly pro-life,” objected to “an entry that my campaign staff had posted on my website—an entry that said I would fight ‘right-wing ideologues who want to take away a woman’s right to choose.’”

Obama said that the doctor “assumed I was a reasonable person, but that if I truly believed that every pro-life individual was simply an ideologue who wanted to inflict suffering on women, then I was not very reasonable,” and that the doctor had written to him, “I do not ask at this point that you oppose abortion, only that you speak about this issue in fair-minded words.”

Obama said he “thanked” the doctor for his letter and learned an important lesson from him: “I didn’t change my position, but I did tell my staff to change the words on my website. And I said a prayer that night that I might extend the same presumption of good faith to others that the doctor had extended to me. Because when we do that—when we open our hearts and our minds to those who may not think like we do or believe what we do—that’s when we discover at least the possibility of common ground.”

The crowd loudly applauded the tale. But it is a feel-good story that doesn’t add up to much: Obama deleted a few words from his website, opening his heart and mind not to unborn children—who are crushed under this specious “common ground”—but to a potential voter.

The self-absorbed character of the event is difficult to overstate, as Father Jenkins and Obama took turns patting each other on the back for their shared commitment to “dialogue,” as if the issue of abortion involves merely a debating match rather than a daily, ongoing, and massive injustice. As Notre Dame and Obama congratulated themselves for a renewed commitment to “open hearts, open minds, and fair-minded words,” unborn children were dying unfairly under his policies—a grim reality easily forgotten in a glib, 24/7 cable television culture that treats politics like a harmless exercise in forensics.

Obama’s visit to Notre Dame was one more reminder that examining the fine print in his policies is always more instructive than listening to his innocuous- sounding phrases. For example, in one piece of news that came out of his speech, he told graduates that he favors a “sensible conscience clause” for hospitals. Sounds reasonable, right? Until one asks: What does “sensible” mean? Requiring doctors to refer for abortions if they decline to perform them?

Similarly, he encouraged graduates to bring faith into public life, then suggested that faith is too doubtful for any real use in public life:

Hold firm to your faith and allow it to guide you on your journey. Stand as a lighthouse. But remember too that the ultimate irony of faith is that it necessarily admits doubt. It is the belief in things not seen. It is beyond our capacity as human beings to know with certainty what God has planned for us or what he asks of us, and those of us who believe must trust that his wisdom is greater than our own.

This doubt should not push us away from our faith. But it should humble us. It should temper our passions, and cause us to be wary of self-righteousness. It should compel us to remain open, and curious, and eager to continue the moral and spiritual debate that began for so many of you within the walls of Notre Dame. And within our vast democracy, this doubt should remind us to persuade through reason, through an appeal whenever we can to universal rather than parochial principles, and most of all through an abiding example of good works, charity, kindness, and service that moves hearts and minds.

Were this faux-thoughtful advice sincere, he would subject his own secularism to these reservations. But he doesn’t; he just assumes it enjoys a monopoly over reason, and that the Church’s opposition to abortion and gay marriage rests on dogmatic opinion rather than certain truth.

A beaming Father Jenkins seemed to consider the day a great success, but Church historians of the future will likely look back upon his “fruitful dialogue” with the “culture” as just one more craven concession to it.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.