The day following the election of the archbishop of Buenos Aires to the papacy, I must have received fifty e-mails from friends and family asking if I knew the man or had any comment on him. What struck me was how little we knew about him. If he has a paper trail (the previous three popes had extensive ones), it is yet to reach us, though I did read the following comment from a statement in Buenos Aires a couple of years ago: “We hope legislators, heads of state, and health professionals, conscious of the dignity of human life and the rootedness of the family in our peoples, will defend and protect it from the abominable crimes of abortion and euthanasia, that is their responsibility.” I presume Ignatius Press is busily translating and preparing what we do have for English publication. What we do have are actions taken and gestures made while he was Jesuit provincial and a bishop in Argentina. He rides the bus, leads a simple life, and loves the poor.

Though Cardinal Bergoglio was reportedly a contender in the previous conclave, his age and health seemed to militate against him, but in retrospect only “seemed.” They turned out to be advantages. We are reminded that Pope Leo XIII was elected as a sort of interim pope but he lasted twenty-five productive years. With the voluntary retirement of Benedict XVI, the whole issue of a pope’s health has changed. I have heard it said that Pope Francis has only one lung. Well, I figure if Schall can get by with one eye, the man on the Chair of Peter can get by with one lung!

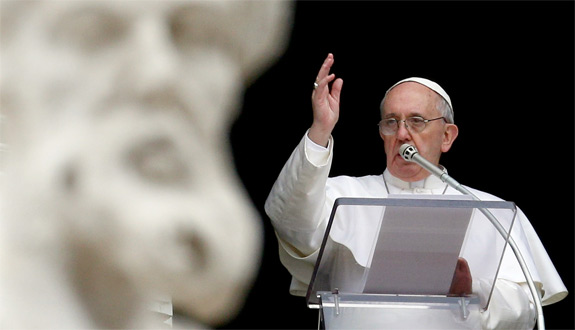

Two things immediately strike us about Pope Francis: he is from Argentina and he is a Jesuit. Neither one of these may mean much in the long run. He is now in an office that transcends both, but does not necessarily bypass them. Pope Francis will clearly, I think, have cordial relations with Benedict XVI, as well as with the Jesuit General and the Latin American Bishops’ Conference, not to mention the Franciscans. He is a friend of Opus Dei. With John Paul II and Benedict, we have become used to the attention paid to the various Orthodox traditions, and this connection will continue. Francis was a friend of the Ukrainian Catholic community in Argentina, and he will be meeting this Wednesday with delegates from several Eastern Catholic Churches.

It seems pretty well settled that Francis is Francis of Assisi, not Francis Borgia, Francis Xavier, or Francis de Sales. Yet probably every Francis is ultimately named after Francis of Assisi. We think of Chesterton’s book on St. Francis of Assisi. It helps to know who a man’s heroes are, as I think we are defined by our heroes. If we consider the names that he did not take—Linus, Michael, Eusebio, Alexander,—we cannot help but concluding that Francis was chosen for virtues that Francis manifested in his own life.

In his earlier administration in the Jesuits, Pope Francis showed that he understood the temptation to ideology that lies in much modern political and religious concern for the poor. One might say that most modern ideology is presented in the name of “helping the poor.” This concept is its moral grounding. The problem is usually not that of intention but of fact. Does the program or attitude advocated help the poor? Even more basic: do we want the poor to remain poor? Is the purpose of Christian revelation to make everyone poor and keep them that way so that we can “care” for them and thereby give ourselves a seemingly lofty purpose? We should not approach the problem of poverty without some idea of why the poor are poor, or how they might cease to be poor.

The trouble with such considerations is that the fact and feeling of poverty can diverge. If I live in a home that is worth a million dollars, it is possible that I feel deprived if the folks all around me are in houses worth three million. But no one would say that I am poor. The same holds true in the barrios. There are richer and poorer “poor” people. And there are poor people who try not to be poor and others who are content permanently to receive aid without their doing anything to earn it. It has long been pointed out that usually a relation exists between envy discussions and poverty discussions. One man’s poverty is another man’s riches.

Moreover, in the modern world, a close connection exists between ecology and poverty. Paul Johnson rightly pointed out that, at the fall of Marxism, the left often migrated into ecology. Why? It gives to the state vast new powers over the people, over both their desires and their very existence. Indeed, a good part of ecology thinking is based on the need not to grow so that men can take care of everyone but to reduce the population to two or three billion so that we do not have many to take care of. The “increase and multiply” admonition of Genesis, which is the major stimulus for man to develop ways of taking care of himself, is replaced by a reluctance to do anything but keep the planet in a state of permanent under-development in the name of “future” generations that may or may not ever exist or exist with only our present level of development.

It is one thing for a member of a religious order with a vow of poverty to live more like a poor man. It is quite a different thing if he wants everyone to live like he does so that he does not know how or refuses to make the world more abundant and prosperous by the application of mind to matter. Thus, we not only want to know how a man lives, but what he thinks about how he lives. For whom is his example intended? The reason the poor are poor is not because the rich are rich. Indeed, if we have a no growth theory, which lacks the incentives to create riches, we must end up with a “redistributionist” mentality. We think that one man’s wealth is taken away from some other man unjustly just because there is disparity. What caused the disparity is often overlooked.

In the modern world, probably the greatest producers of poverty are government plans to alleviate it. Not only is this a problem of poverty but one of freedom also. If we misunderstand the causes of poverty and fail to understand what causes wealth, we will make everyone poor in the noble name of helping the poor. A further element arises from Benedict’s encyclicals, which warn us of the limits of government bureaucracy in dealing with the poor. Modern governments often want and demand complete control of the economy so that they are the ones who “take care of the poor.” In this sense, no room is left except for state control in the name of helping the poor, usually with policies of abortion, “gay marriage”, euthanasia, and other such devices to control population.

Francis has urged Argentines to not come to Rome to celebrate his elevation to the papacy. He suggests they stay at home and spend the money on the poor. Now if we consider that a good part of the income of Romans and Italians has to do with the tourist trade, by which many poor are helped, we can see some of the problems connected with such suggestions. Do we also advise Japanese, Germans, Swedes, and Mexicans not to come to Rome? What would this approach do to world economy? If we universalize this admonition we also imply that the traveling to see beauty and worthwhile human things has something wrong with it. We reduce human life to one dimension.

And if we all stay at home and help the poor, just what do we do? If we take all the existing world wealth and simply distribute it, what would happen? It would quickly disappear; all would be poor. We need ways to create wealth. We sometimes forget that the only real resource in the world is the human mind, not, say, oil or minerals or land. Without thought, these raw materials are useless. We often project what we can do in the future based on a present technology that is soon out of date. Henry Adams, in his studies of the Virgin, said that she was a greater producer of wealth than the dynamo. And one of the sources of wealth in the Eternal City itself was the beautiful things that the popes inspired to which all the world comes to visit. It is difficult to see how the world would be better if everyone stayed at home. We come to visit, see, and experience beautiful things precisely to show we are not bound to material things.

Some have suggested, on the basis of Francis’ understanding of what a bishop is, that he will not travel as John Paul and Benedict did. He will concentrate on ruling the Diocese of Rome and suggest that other bishop do the same. He will concentrate on appointing good bishops. Francis has already made it clear that he does not want priests engaging in political movements. He does not consider opposition to abortion to be simply “political.”

So, in the light of such speculations, what are we to make of this new bishop of Rome? The cardinals have chosen a worthy man. His will be a different papacy. Benedict and John Paul have pretty well cleared the intellectual scene within the Church and indeed within the world. What remains is what Francis seems to understand midst growing threats of persecution throughout the world including in the democracies. Benedict often told us that we need to live our faith. We find our models in the saints and Francis comes across as a man who understands this well. We are here primarily, as St. Ignatius said, “to praise, reverence, and serve God and thereby to save our souls.” The world can choose not to listen to the brilliance of a John Paul or a Benedict. It can also, but with less confidence, choose to vilify or reject the example of a Mother Teresa in order to reject what she stands for. But a bishop of Rome who sets about governing the Church quietly and firmly in the light of orthodox Christian living may be something else, a completion of what the Holy Spirit has begun in the previous bishops of Rome.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.