I recently interviewed American atheist leader David Silverman on my television show. He became a legend in his own lunchtime recently when his organization’s booth was first accepted and then rejected by CPAC, the Conservative Political Action Conference in Washington, D.C. It’s a grand collection of right-of-center activists, authors, and politicians, and all sorts of groups and causes have booths and displays. There are, of course, atheists at the conference and there is a strong secular tradition within libertarian conservatism.

Silverman’s problem was that his group had purchased enormous billboards labeling all religions a scam. He is evidently not an atheist conservative looking to build bridges with Christian conservatives but a rather aggressive God-hater full of the usual disdain for, and ignorance of, religious faith.

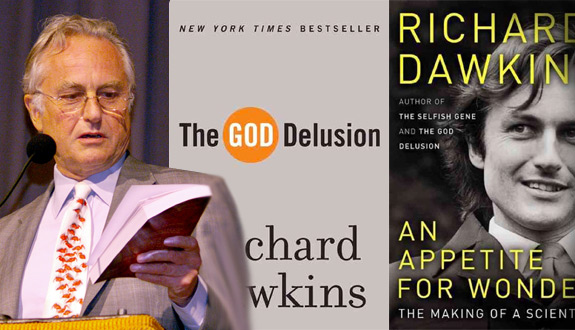

Which brings me to an equally aggressive but more intelligent atheist who is seldom out of the news: Richard Dawkins. In April of 2010, Dawkins announced an initiative to have Pope Benedict XVI arrested when the pontiff made an official visit to Great Britain later that year; the ostensible reason was Benedict’s alleged involvement in the Catholic clergy abuse crisis. Benedict was then 83 years old and in poor health. His already difficult job was made even more challenging, it seems, because of a campaign against him by some Vatican insiders precisely because he was so active in exposing and punishing abusers. It appears this was very likely one of the factors that led to his resignation three years later.

Dawkin’s publicity stunt provides a most revealing insight into the mind and manners of the evolutionary biologist turned atheist celebrity. It certainly provides more insight into the man than does the first volume of his autobiography, An Appetite For Wonder, which appeared last year to far too much acclaim and approval. It often reads as though the author were an extremely agitated caricature, unaware that misplaced hubris is hilarious. Yet Dawkins is not merely some boiling obsessive searching for attention but a genuinely influential thinker and author. He’s not a fool and he surely knew that the abuse horror in the Catholic Church involved, at most, 3% of clergy, that the vast majority of cases were of the past, that abuse rates are far higher in public schools, and that an arrest of the pope was impossible.

The arrest, of course, had been suggested merely for publicity. And it was publicity built on a deeply flawed premise. Perhaps Dawkins does have this selfish, genetic need to be noticed (yes, the pun is intentional). Whenever the cuttings file diminishes, he can be counted on to make another outlandish statement or growling comment, often ill-informed or simply annoying, such as his recent attempt at schoolboy-ish, smutty poetry (described by the fawning Independent as “An innuendo-filled poem of magnificently smutty genetic proportions…”). It’s as regular as clockwork and just as repetitive and boring. The Benedict incident also showed Dawkins as a man supremely comfortable with silencing those with whom he disagrees, as his atheist followers—and they often act in a cult-like manner—demonstrate on a regular basis.

Benedict seldom responded to attacks when he was Pope, but did so last year, after his resignation, in a letter to a more respectful Italian atheist. The pope emeritus explained:

An important function of theology is to keep religion tied to reason and reason to religion. Both roles are of essential importance for humanity. In my dialogue with [atheist philosopher Jürgen] Habermas, I have shown that there are pathologies of religion and — no less dangerous — pathologies of reason. They both need each other, and keeping them constantly connected is an important task of theology.

Science fiction exists, however, in the context of many sciences. … Even within the theory of evolution, a great style of science fiction exists. Richard Dawkins’ selfish gene is a classic example of science fiction.

Exactly, and well said. I bet Dawkins reacted generously and calmly to that one

What has to be realized here is that the man is extraordinarily overrated and seldom questioned by a generally bovine media. As an evolutionary biologist, Dawkins is considered by his peers as a sound and, at one time at least, a cutting-edge academic. To question that would be fatuous. In recent years, however, his academic work and reputation had declined, which is not something he discusses in his memoirs or elsewhere. Frankly, he would be largely anonymous outside of his rather limited field if it were not for his ostentatious atheism, and in that field he has never been considered sound and certainly not cutting edge. Back in 2006, Terry Eagleton began his review of The God Delusion in The London Review of Books with the statement: “Imagine someone holding forth on biology whose only knowledge of the subject is the Book of British Birds, and you have a rough idea of what it feels like to read Richard Dawkins on theology.”

And Eagleton is absolutely right. Dawkins is aggressively eloquent, utterly confident, and dismissively sweeping in his attacks on God and faith, but he is never profound or genuinely compelling. Bertrand Russell was deeper, H.G. Wells was more populist—even silly old Stephen Fry is funnier. Dawkins insists on the same attacks on the same straw men of religion, and he is extremely selective in whom he will debate, having refused public arguments with those he considers “unqualified”—a grotesquely snobbish euphemism and excuse. There are several North American Christian apologists who would be delighted to take on Dawkins, if only given the opportunity.

The noted philosopher and former atheist Dr. Edward Feser, author of The Last Superstition: A Refutation of the New Atheism, wrote that, “Oddly, the rhetoric of the New Atheist writers—Richard Dawkins among the most prominent—sounds much more like that of a fundamentalist preacher than like anything I read during my atheist days. Like the preacher, they are supremely self-confident in their ability to dispatch their opponents with a sarcastic quip or two. And, like the preacher, they show no evidence whatsoever of knowing what they are talking about.”

At the Rally for Reason in 2012, after that terribly brave Australian performer Tim Minchin had repeatedly sung, “F*** the Motherf****** Pope”, Dawkins told the hysterical crowd, “Mock them, ridicule them in public, don’t fall for the convention that we’re far too polite to talk about religion. Religion is not off the table. Religion is not off limits. Religion makes specific claims about the universe, which need to be substantiated. They should be challenged and ridiculed with contempt.”

There was something almost fascistic about this and worryingly oppressive. Also, utterly absurd. Too polite to talk about religion! Where has Dawkins been; in what world does he live? It’s been open season on Christianity for almost a generation now, and the last acceptable prejudice in so-called polite society is anti-Catholicism. Dawkins’ greatest achievement, in the end, is Dawkins. He has closed rather than opened the debate around faith and reason, and made life far more difficult for informed believers as well as informed skeptics. But closing the debate is sadly typical now within many atheist circles. Rather than listening and speaking so many atheists want to silence and shout. “Can you hear us God?” Yes, He can. As for Professor Dawkins, he doesn’t seem to care, and would never even want a booth at CPAC!

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.