Tick-tick-tick, goes the clock.

We measure time in seconds, minutes, hours, days; scientists, in nanoseconds and light-years, giving us the impression that time is quantitative and fixed.

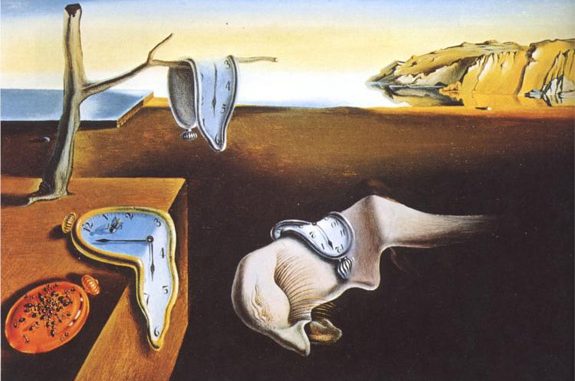

Not so fast, my friend, as ESPN’s Lee Corso is wont to say. The human experience of time is varied, even mysterious.

Time is commonly measured by a chronometer (clocks, etc.), though these devices are rapidly being replaced by smartphones and the like. The fixed interval, tick-tick-tick, is the same, however, tricking us into thinking of time as something external to our lives and experiences.

Einstein and general relativity altered the way many think about time. Space and time are intertwined. Speed, especially as one approaches the speed of light, affects time. This means that time is not fixed—immutable—everywhere, that time is not identical for observers in relative motion. The quantum theory of gravity, or quantum gravity, adds another layer of complexity (many would say obscurity) to the understanding of time. So, even in the scientific realm, time isn’t the tick-tick-tick we once considered it to be in the days of Newtonian physics.

There is also the matter of human perception. Who hasn’t experienced time as either racing by or moving at a snail’s pace, depending on what we are experiencing—joyful or tedious activities? Within each person, there can be a profound sense of time accelerating or standing still.

Human memory is a place where time can be…well, unreliable. There are periods of time we remember vividly, almost minute by minute. Other periods of time are a blur, barely remembered. Some memories are transformed as meaning gradually illuminates past events. This phenomenon has biological and psychological explanations, but there is also a spiritual dimension to human memory, with some experiences having the sense of being “outside time” as it were.

The perception of time is affected by historical and cultural settings. Consider a medieval farmer, for whom time was linked to the flow of seasons and capricious weather; or to a street urchin in 18th century Paris, living from moment to moment without the luxury of pondering the past or the future; or modern man, whose day consists of connecting to one “cloud” or another. How different these perceptions of time were, and are.

As for the effect of the passage time on fame and notoriety, a few years pass and the famous are forgotten, or scarcely remembered. When remembered, does the public image of the person resemble the real man or woman?

Science and time get even more complicated. The renowned mathematician and logician, Kurt Godel, inferred that under certain circumstances, there could be no such thing as an objective (fixed) lapse of time. Stranger yet, Godel, a close friend and colleague of Albert Einstein, extrapolated Einstein’s general theory of relativity to suggest that if we were living in a rotating universe, loops in time could be produced so that the normally straight past/present/future timeline could make time travel possible. Yikes!

In my novel, Toward the Gleam (Ignatius Press, 2011), John Hill has a conversation in the Scottish hills with the mysterious Gosdier Jones that goes like this: Jones planted his feet on the path like two tree trunks and rubbed his beard. “I can’t match your wit, but wit is not proof. I’ll put this to you. There are two young men who are standing conventional wisdom on its ear. You may not have heard of them, but they are shattering scientific and philosophical preconceptions: Einstein and Godel. The former says that time itself is relative, and the latter goes further, suggesting that time may not even exist outside of the human mind. Einstein demonstrated that if the physical laws of the universe are immutable, then dimensions like space and time must be relative. If the speed of a ray of light is constant, and if a man on the ground and a man on a train measure it traveling at the exact same speed, then distance and time must be relative—not fixed—because speed equals distance divided by time. To Godel, time is a human construct that speaks to the simultaneity or sequencing of events. Thus, to Godel, time has no absolute reality and may not be real at all. The point is that thinking about a fixed and irreversible time line with past and present events on sequential points is flawed.”

Scientific conjecture can be taken too far, and experience has demonstrated that scientists change their minds as new information is obtained. Even some of Einstein’s ideas have been amended or rejected. Still, we are all time travelers in the sense that we are ordained to move through time. Some experience time as the caressing, enlivening beating of a mother’s heart, others as the tick-tick-ticking of the relentless crocodile in Peter Pan.

It has been said that reconciling human freedom and God’s knowledge of our destiny—and that of all human history—can only be explained if God is outside of time, that is, present in every moment of history, in an eternal “now”.

My dad used to say that a company cannot pay you enough for your time, and to the extent that time is the matrix in which we pursue heaven, he was right, especially if employment with a company doesn’t advance, or impedes, ones salvation. If you believe that man was made for eternity, and if you believe that he is preparing for eternity in this life, then using the gift of time to pursue material wealth, prestige, power, pleasure for pleasure’s sake, is the equivalent, in a secular sense, of tossing gold coins out a window. The challenge we face every day is that our culture, the water in which we swim, seduces us into believing that our time should be single-mindedly applied to these acquisitive ends.

When we talk about a “fish out of water”, we imagine danger and impotence, but don’t we desire to become this fish out of the water of time in which we are now immersed, so that we might share God’s great adventure in His eternal “now”.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.