I came home from a sobering conference on climate adaptation and read the National Catholic Reporter’s May 20th editorial “Climate change is church’s No. 1 pro-life issue.”

While I am about to present a few concerns with the editorial, I want to applaud its intent and much of its content. Anthropogenic climate change is past debating. It’s an issue that will impact—and one could argue already is impacting—human life. As the editorial rightly observes, “[t]his is a human life issue of enormous proportions.” And I agree with its proposal that “[t]he Catholic church should become a major player in educating the public to the scientific data and in motivating people to act for change”—although I don’t know why “church” is not capitalized.

And while there is much from the climate conference that I wish to share—and will over the next few weeks—for now my attention is turned toward my friends at the Reporter and their troubled call for us to move forward.

First, let’s consider the title.

Is climate change the “No. 1 pro-life issue”? The editorial’s author doesn’t say this, but the header does. Now, anyone who has had their work in print knows that headlines are typically the work of someone other than the author—and that someone may not understand the author’s intent. And yet, there in large letters is the claim that climate change is more important than all other crimes against humanity—which I suppose includes legalized forms of murder, like abortion, which has as its aim the death of innocents. Issues like climate change arise for reasons other than murder.

Thus the assertion in this headline is as bold as it is wrong.

And anyway, why are we ranking life issues? One moral theologian I spoke with today said it was “silly” for such a choice to be offered. I would add that such reckless assertions only cloud what should be straightforward. For those of us who are responding to climate change in our professions, the last thing we need is more shadow.

From this problematic title we turn to a problematic statement:

If there is a certain wisdom in the pro-life assertion that other rights become meaningless if the right to life is not upheld, then it is reasonable to assert that the right to life has little meaning if the earth is destroyed to the point where life becomes unsustainable.

In most Catholic circles that I am aware of, we take for granted that the right to life presupposes all other rights, since no right is of any value if one is dead. As for where the editorial takes us—the destruction of the earth’s ability to sustain life—well, I simply ask for a little more nuance and some sound, scientifically grounded realities. I certainly don’t want to see what happens should our planet be subjected to carbon dioxide levels much higher than they are today—although they probably will go much higher. The consequences to people and ecosystems will be terrible. But the world will adapt to such levels and human life will still be possible even if human civilizations, as we know them today, can’t.

Practically speaking, a growing part of my job requires me to understand what will happen to water-pollution control infrastructure at varying projections of greenhouse gas emissions and the resulting consequences. And it seems that we are already seeing these consequences. Already there are conversations in my office and throughout the nation about communities retreating and the relocation of infrastructure. Those issues are difficult enough to tackle without hyperbole about cascading climate consequences that will make life—even human life—impossible to exist.

(I have to also note—since it is related to the above—that the editorial for some reason thinks this statement was wise to add: “While the church has taken it on the chin for centuries-old condemnations of scientific truths …” If this is a reference to Galileo, than the author(s) should have read a little more about this oft-used anti-Catholic trope.)

Finally, the editorial concludes with some sound suggestions and a glaring oversight.

Catholic high schools and colleges have the freedom to explore these vital issues from both the scientific and ethical perspectives. They can bring theological perspectives to bear on the issues. Educators and students could devise ways to become active at all levels, from homes, to communities, to states, to advocating for legal measures to offset the effects of global warming.

Finding a fix for climate change and its potentially disastrous consequences, particularly for the global poor, is not the work of a single discipline or a single group or a single political strategy. Its solution lies as much in people of faith as in scientific data, as much or more in a love for God’s creation as it does in our instinct for self-preservation.

The solution will be found in none of these things, although many of them are necessary. To put it simply: The problem is sin. The solution is grace—and our cooperation with it.

At the climate conference this week, it was clear to me that secular voices are growing frustrated—even afraid. The good efforts of many seem not to be helping, which is why one (very good) workshop on enlisting the aid of psychology was standing-room only. (More on that later.) I sense that the authors of the National Catholic Reporter editorial are similarly frustrated at where things stand. I am, too.

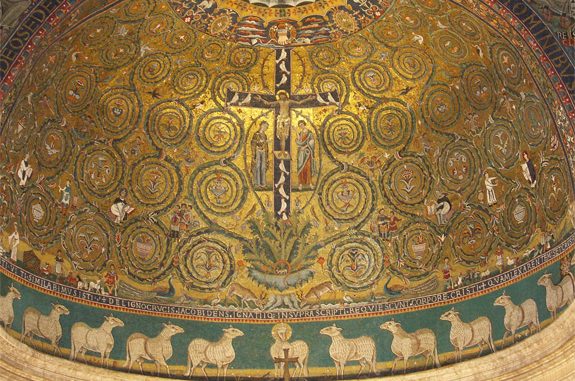

But as Catholic ecologists, we must be upfront that the Church brings to this global symptom of human sin something more than lectures and laws. She brings the transformative Gospel of Jesus Christ and the grace that allows this transformation to take root and flourish.

As Christ tells us in the Gospel from this Wednesday, “Whoever remains in me and I in him will bear much fruit, because without me you can do nothing.” (John 15:5)

What this means for ecology has been stated many times by popes and bishops. Bishop Dominique Rey of Diocese of Fréjus-Toulon, France taught this truth with startling clarity in his ecological pastor letter. And so to close, here are two passages from the bishop that say what I think the National Catholic Reporter wanted to:

We are faced with a moral crises: that is to say a crisis of human choice and human action. Hence, the root of the problem resides in man’s heart rather than in strictly economic or industrial concerns.

In the Eucharist, we find the possibility of a renewed understanding of the created world. The Eucharist allows us to uncover the basis of an integral human ecology; here we find the antidote to radical individualism and collectivism. The Eucharist allows us to find Jesus’ face in every person, most especially the poorest. It also enables us to welcome in creation a gift from God and to thank him continuously for it.

[Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on the “Catholic Ecology” website.]

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.