In the 1980s, Richard John Neuhaus famously criticized the “naked public square”: the notion that public life—politics, business, education—should be devoid of religious content. Advocates of the naked public square see religion as inherently divisive. In a pluralistic society, they say, it’s best to keep such potentially explosive issues to ourselves.

A similar understanding has come to dominate many academic disciplines, where personal beliefs concerning matters such as religion are thought to have no importance—or discouraged from having any bearing—on scholarly research or writing.

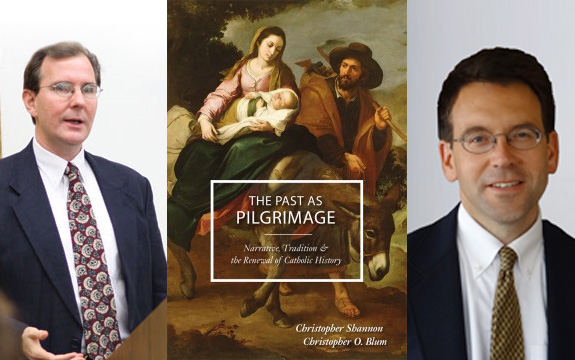

In The Past as Pilgrimage: Narrative, Tradition, and the Renewal of Catholic History (Christendom Press, 2014), Christopher Shannon and Christopher O. Blum launch a frontal assault on the idea that historical scholarship should be theologically neutral. Dr. Shannon is professor of history at Christendom College in Virginia, and Dr. Blum is professor and academic dean at the Augustine Institute in Denver. They corresponded recently about some of their book’s central points.

Schmiesing: First, some groundwork. Some people naturally love history, while some hate it; many are indifferent. You see history as playing a vital role within the Catholic tradition. Why should the past be of interest to those who are serious about their Catholic faith?

Dr. Blum: The simple answer, of course, is that the past matters because Almighty God has entered the human story: first, through his messengers and prophets; then, in the life, death, and resurrection of his Son Jesus Christ; and finally, through the presence of his Holy Spirit in the Church. It is because of these events and the words of God recorded in the Bible that Popes Francis and Benedict XVI have affirmed that the current crisis of faith is also a crisis of memory. Without a real connection—alive in our memories—to God’s saving work in the past, we can hardly be Christians.

Dr. Shannon: History is not only essential to Christianity, but is perhaps the most distinctive feature of Christianity among the religions of the world. Every faith has a history, but Christianity is a historical faith whose truth depends upon real, as opposed to mythic, events. We can only know our faith through knowing these events and how they relate to each other. The Church teaches timeless truth, but lives truth in time. Philosophy and theology do not comprise the whole truth of the Church. We cannot fully know the Church without knowing how it has lived—that is, without knowing its history.

Schmiesing: As a fellow Catholic historian, I found your arguments to be both inspiring and challenging. You describe a vision of the nature and purpose of historical scholarship that is more than simply trying to uncover and reconstruct the past. For a Catholic, what is—or should be—the purpose of exploring and writing about history?

Dr. Shannon: The accurate reconstruction of the past is a necessary, but hardly sufficient, aspect of Catholic history. Anyone who believes that history has meaning is looking for something beyond empirical accuracy. Catholics believe that God speaks to his people through history—albeit in often cryptic and seemingly inscrutable ways. The study of history should be in part an act of listening to the voice of Jesus Christ expressed primarily through the life of his Church, but also in the life of the world outside the Church proper.

Dr. Blum: Yes, and we also argue that the complexity of the moral life today coupled with the widespread amnesia or loss of what Benedict XVI called “deep memory” means that our generation stands in need of historical study that will nourish our sense of what a Christian life well-lived looks like, both for the individual and for Christian communities. From the examples of the saints and healthy Christian communities of the past, we are better able to imagine our own next steps towards justice and personal holiness.

Schmiesing: It is clear that you and I studied history in graduate school during the same era: Peter Novick’s That Noble Dream was on the reading list! Novick recounts the story of historians’ “quest for objectivity.” You argue that the goal of objectivity is wrongheaded. Historians all operate within a narrative tradition, you say, and they should be unashamed of and open about that. But don’t objectivity and concern for the truth go hand in hand? Are you saying that Catholic historians should be just another interest group with a partisan agenda, like Afrocentric historians or gay/lesbian historians?

Dr. Blum: This is a great question because it points to an essential distinction between the virtue of truthfulness and the ideal of objectivity. Truthfulness is required for any intellectual or artistic endeavor to achieve its end, and is, moreover, absolutely necessary to the Christian’s daily walk in grace.

Dr. Shannon: Yes, but the ideal of objectivity is really something quite different from truthfulness. Objectivity suggests detachment, most obviously from base prejudice, but in theory even from concern for higher truth. In practice, this principled detachment has been exercised selectively and somewhat hypocritically. A secular historian who claims agnosticism as to the truth of Christianity might at the same time have no reservations about denouncing African-American slavery as a violation of human dignity. Were the kind of confessional Catholic history we describe to gain a hearing among professional historians, it might at first appear as yet another interest group akin to Afrocentrism. Still, Catholicism’s commitment to universal truth suggests its potential to overcome the divisions of interest group history, incorporating the partial truths of these particular histories into a broader synthesis.

Schmiesing: You highlight a few figures—Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, John Henry Newman, Eamon Duffy—who are in your estimation excellent Catholic historians. What is it that makes a writer such as Duffy deserving of our attention?

Dr. Shannon: Eamon Duffy’s reconstruction of the devotional world of late-medieval Catholicism in The Stripping of the Altars is both a work of scholarship that will stand the test of time and something of a devotional text in its own right. For a Catholic seeking to understand what it means for faith to be a whole way of life, there is no better work of history. At the same time, Duffy has proved himself capable of distilling his tremendous erudition into popular, accessible forms. In this, he is a model for all contemporary historians.

Dr. Blum: I have long admired Eamon Duffy and would put him in a select company of living Catholic historians—together with Crusade historians Jean Richard and Jonathan Riley-Smith, and specialists on the early and medieval Church Robert Wilken and Augustine Thompson, O.P.—as examples of historians whose research and writing has been of the highest professional quality and consistently guided by their Christian faith. It is quite a tight-rope to walk, and each has done so with considerable grace.

Schmiesing: In a Church history class I teach, I have for years used the lives of the saints as windows into the ecclesiastical and secular histories of their time. I was thus fascinated by your chapter, “At the School of the Saints,” which articulates a rationale for this approach. The chapter focuses on another model for Catholic historians: Pope Benedict XVI. What is his contribution to the discussion?

Dr. Blum: In the first place, Benedict XVI has, in effect, issued a challenge to Catholic historians: if the Pope can devote his precious time to calling our attention to the saints—as opposed to the many other topics of teaching he could have chosen for those dozens upon dozens of general audience addresses on the saints—then surely Catholic historians can and should follow suit.

Dr. Shannon: Yes, clearly we need to present the lives of the saints in greater depth and detail than Benedict could accomplish in his brief addresses. Still, we must avoid the other extreme of the massive, thousand-page biographies that remain, somehow, the best-selling forms of popular history.

Schmiesing: For all of us who teach history in any way—as preachers, writers, religious educators in RCIA, CCD, schools, or colleges—what are one or two concrete things we can do or keep in mind so as to be better Catholic historians?

Dr. Shannon: First, we must always approach the past with humility, knowing that our subject matter is both the saints and the sinners who make up human history. Confessional history always risks sliding into a facile triumphalism, but nothing could be further from authentic Catholic history. St. Augustine long ago put forward a vision of history as a struggle between the City of God and the City of Man, only to caution that the two are often inextricably bound and difficult to distinguish from each other.

Dr. Blum: Also, I think that as interpreters of the Catholic past, we need to avoid letting our agenda be set by the secular opponents of the Church. The story of the faith is the world’s most beautiful and captivating story, for it is nothing less than the revelation of God’s love for every man and woman who shall ever live. When we tell that love story, either as a whole or in any of its parts, we need to make sure that we communicate its high drama and faithfully testify to its loveliness.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.