![]()

The goal of the Christian life is to become gods. This claim probably will strike many readers as exaggerated at best and downright heretical at worst. But this is what a Catholic priest or deacon says at every single Mass as he prepares the wine for consecration. “By the mystery of this water and wine,” he prays silently, “may we come to share in the divinity of Christ who humbled himself to share in our humanity.” This prayer suggests that the mingling of water and wine is both a symbol of and vehicle for our sharing in God’s divine life, what the Christian tradition has called divinization or deification or, in Greek, theosis. Simply put, God wants—to borrow a phrase from Augustine—to “turn his worshipers into gods” (City of God, 10.1).

While this claim sounds foreign, it is in fact the traditional teaching about salvation that Catholics, Orthodox, and even Magisterial Protestants have always held in some form. God doesn’t just want to save us from our sins (though this is a necessary first step); he wants to save us for himself, for immersion in his own blessed Triune life of love, for a glorious transfiguration wherein our humanity becomes resplendent with his divinity. And how does God intend to do this? Through the sacraments which communicate his life to us.

The liturgical context

Because this traditional teaching is not widely known, it is with gratitude that we should welcome the small collection of essays, Divinization: Becoming Icons of Christ through the Liturgy, edited by Fr. Andrew Hofer, OP. Fr. Hofer, who teaches on the Pontifical Faculty of the Immaculate Conception at the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C., has gathered a handful of scholars, chosen for their ability to teach the faith in clear and compelling ways, to write on various aspects of divinization and the liturgy.

David Fagerberg discusses how divinization is connected to evangelization; Andrew Swafford delves into some of the Biblical roots of divinization; Fr. Hofer contributes an essay on how Aquinas’ teachings on divinization can help people in the pews; Daria Spezzano articulates why divinization is important for authentic liturgical renewal (this essay alone is worth the price of admission); and Michael Sirilla explores divinization in the New Evangelization. Together, these essays fill a critical gap in popular Catholic and scholarly literature.

Hofer argues that the proper context for thinking about divinization is the liturgy for God has chosen the liturgy as the primary locus for communicating his life to us. Our divinization begins in baptism (or in the first touch of grace which leads to baptism), wherein the Holy Spirit makes us sons and daughters of God. Sons and daughters of God! We say that so often, we don’t realize how radical it is. We are, by nature, sons of Adam, broken and alienated from God. But in baptism, we are incorporated into Christ, we become a member of his Body, and in doing so we share in the things that are his. We becomes sons (and daughters) in the Son. In baptism, our nature is not only healed of original and personal sin, but is elevated because it now shares in Christ’s divine nature.

Mary provides a good model for what happens to us in baptism. Just as Mary said “Yes” to God and the Holy Spirit formed Christ inside her, so too in our baptism do we say “Yes” to God and the Holy Spirit forms us into Christ-ians—into little Christs. The Catechism is rather striking on the divinizing power of the Holy Spirit in this process: “As fire transforms into itself everything it touches, so the Holy Spirit transforms into the divine life whatever is subjected to his power” (CCC, 1127). In baptism, we become like the Burning Bush, a creature on fire with God’s presence but not consumed. While we never cease to be human, the Holy Spirit transforms us into divine life.

This transformation is not complete on earth, but only in the Resurrection when God will be “all in all” (1 Cor 15:28). Until that time, we are on pilgrimage and the Eucharist is our food for the journey. Hofer quotes a post-communion prayer that shows what we believe the Eucharist does to us:

Grant us, almighty God,

That we may be refreshed and nourished

By the Sacrament which we have received,

So as to be transformed into what we consume.

The Eucharist is the Body of Christ; the baptized congregation is the Body of Christ. We receive what we are. We are a mixed Body, a body with wheat and weeds, but the Eucharist is the “self-same body of the Lord” which died and rose from the dead (as Ignatius of Antioch put it in the second century). When we consume the Eucharist, we are “transformed into what we consume.” As our grandmothers always told us, “You are what you eat!”

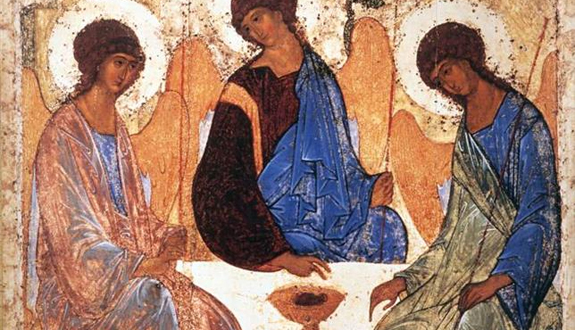

Becoming icons

This insight brings us to the subtitle of Hofer’s book: Becoming Icons of Christ through the Liturgy. In the liturgy, we are transformed into Christ. The image of God in us, which was marred by sin, is restored to God-likeness. Christ begins to shine in us. We become an icon or image of Christ because his life is manifest in us. We can begin to live out Christ’s startling statement, “You are the light of the world” (Matthew 5:14), not because we are so wonderful or intelligent or good in ourselves, but because we are rooted in Christ, who is, in fact, “the light of the world” (John 8:12). Because we share in his divine life, we light up the world with his light.

Hofer wisely chooses the image of an icon as a way of thinking about this mystery. An icon is not just picture or painting of a holy person or event. An icon is a window into the invisible world, a boundary between heaven and earth, a meeting place of human and divine. An icon invites our participation in divine things through created things. This is what we become through the liturgy. The liturgy draws us into God’s divine life, filling us with his holiness, so when people encounter us, they encounter God—not because we are God and should be worshiped, but because God’s life permeates our being and so we become that meeting place of human and divine.

A popular analogy the Church Fathers often used was an iron in the fire. By itself, the iron is cold and hard, but after being placed in the fire, it takes on all the qualities of fire so that it feels like fire and looks like fire and acts like fire. That is what happens to us when we are immersed in God through the liturgy: we are set on fire with God so that others can be set on fire too. God communicates his “light” and “heat” to us, so we can illumine others and set them on fire too.

Fr. Hofer quotes the wonderful prayer, likely composed by John Henry Newman, which Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity recite after every Mass:

Dear Jesus, help us to spread your fragrance everywhere we go.

Flood our souls with your spirit and life.

Penetrate and possess our whole being so utterly

that our lives may only be a radiance of yours.

Shine through us, and be so in us,

that every soul we come in contact with may feel your presence in our soul.

Let them look up and see no longer us, but only Jesus!

Immersed in the Eucharist, which they celebrate each morning, the Missionaries of Charity pray that their lives might be conformed to what they have consumed so that they can bring God’s divine life to others. They pray for divinization so that they might be icons of Christ for all they meet that day.

Divinization and evangelization

This brings us to the most unique contribution of Hofer’s book, namely, how divinization inevitably leads to evangelization. This is a much needed element in divinization literature. The teaching on divinization can often seem like a beautiful doctrine which each person, through private devotion, is invited to embrace and live. Divinization gives us a beautiful account of our destiny as humans made in the image and likeness of God, but it is not at all clear how this has anything to do with our neighbor or the social teachings of the Church. Often, divinization seems like a compelling vision of personal piety, but one that is detached from the rest of the Christian understanding of reality. The essays in Hofer’s book begin to bridge the conceptual gap by articulating the intrinsic connection between divinization and evangelization.

In his essay, “From Divinization to Evangelization: An Overview,” David Fagerberg, who teaches liturgical theology at the University of Notre Dame, quotes then-Cardinal Ratzinger’s definition of evangelization. “To evangelize means: to show this path [toward happiness]—to teach the art of living.” We have to teach people the art of living, to show them the path to happiness, which means, in short, teaching them that they, too, are called to be divinized. Deep down, Fagerberg argues, all people want this. We are made for God and our heart is restless until it rests in him. Nothing less than God will ever fulfill us; no path toward happiness that the world offers will make us happy. No way of life that is not God’s will ever be enough. Fagerberg quotes Ratzinger again: “Man is not satisfied with solutions beneath the level of divinization.” Our divinization enables us to evangelize. Our evangelization means teaching people how to be divinized.

The five essays of this slender volume provide an accessible introduction, and even at times a practical guide, to divinization for those unfamiliar with this central teaching of our faith. But they will also challenge those who know the doctrine well. While not all the essays stay equally close to the theme of the book, each offers helpful insights into the meaning of divinization. One unfortunate lacuna is that there is no real discussion of how the proclamation of the word fosters our divinization. A real opportunity was missed to reflect on the divinizing power of Scripture in the liturgy. Still, this should not stop anyone from picking up this fine volume which will deepen our understanding of salvation, dispel the false notion that divinization is the exclusive province of Eastern Christianity, and, most importantly, will foster an increased appreciation of the radical transformation we experience at every Mass, and how, as icons of Christ, we can “go in peace to love and serve the Lord.”

Divinization: Becoming Icons of Christ through the Liturgy

Edited by Andrew Hofer

Chicago: Hillenbrand Books, 2015

Paperback, 150 pp.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.