In the burning desert heat, there stands a man dressed all in black. His face is hidden. In his hand, he holds a blade. Kneeling beside him, dressed in florescent orange and with arms tied behind his back, is Jim Foley, American photojournalist and ISIS hostage.

This is, for many, the first image they saw of the captured American. It was also to be the last. Minutes later Foley was dead, sickeningly and publicly executed by his captors.

This murder, in particular, revolted, and still revolts, any civilized human being. To take a man life’s for little more than propaganda is bad enough; to do so for maximum publicity in front of cameras is an abomination. The public nature of the killing did indeed have an effect; it woke people up to the ghoulish barbarism of ISIS.

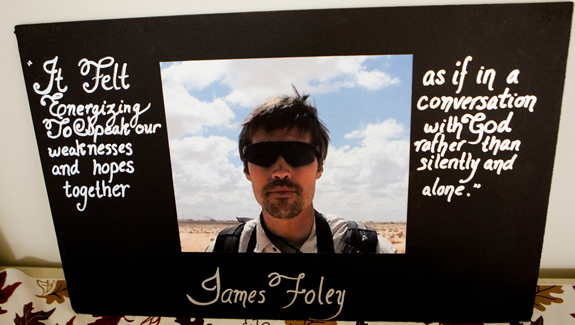

The world also took note of Jim Foley. A new film has been released called Jim: The James Foley Story, and through it many will come to know its subject better. Nevertheless, it is a controversial movie for it suggests that, while being held captive, Foley converted to Islam.

This contention is all the more upsetting given the media coverage about Foley following his untimely death, particularly in the Catholic media. In fact, at the time, one of the most popular posts online about the journalist was Catherine Harmon’s Catholic World Report article on Foley’s first period of captivity and his devotion to the Rosary and his faith.

Foley came from a devout Catholic family. In the film, when his parents are being interviewed, there is a crucifix on the kitchen wall and, in their sitting room, a prominent picture of the Sacred Heart. One of the weaknesses of the film is that this aspect of the lives of the Foley family—prior to, during, and since the hostage-taking—is never fully explored.

What is examined in more detail is the public life of Jim Foley. The film is good at revealing some of the reasons why he went to war zones to photograph those appalling scenes and to report them to the wider world. The filmmakers have done an excellent job of assembling interviews with his fellow photojournalists, all of whom were friends of Foley, and who risk their lives in areas ravaged by conflict and its devastations. There are some truly dreadful video sequences, shot by Foley in Syria, showing the slaughter of civilians—many of whom are children. The film is as much about the vocation of the war reporter as anything else; as the film progresses, with its extended sequences of war, one realizes how hard it is for most of us to understand what motivates such reporters. Here are men and women who head toward the sound of the guns when everyone else is making in the opposite direction.

How Foley ended up living in and, to some extent, for such dangerous pursuits is, even now, unclear. What the documentary suggests is that he was unable to settle into a conventional life. His brothers and sisters are all interviewed; they are professional people with careers and families, people with whom an audience can readily identify. But a regular 9-to-5 job, a home and a family, were not to be for Jim—his life was lived differently, often to the bafflement of those closest to him. Nevertheless, what his siblings grew to understand, eventually, was that the path their brother had chosen was altogether unique.

There are many moving moments in this film. One is when a brother takes Foley to a Boston comedy club after Jim’s release from his first period of captivity. The club is in uproar. Everyone is laughing, having a good time, except for one person. Jim Foley is sitting silently, staring ahead, motionless. Maybe, in his short life, he had already seen too much? Or was he suffering from post-traumatic stress? His brother still doesn’t know; but, that night, on leaving the club, the brothers embraced for what would be the last time. Jim then left to follow a path that few around him really understood.

Until I watched this film, I hadn’t fully grasped that Foley had first been held hostage in Libya in 2011, eventually being released after 44 days. Many people would have stopped reporting overseas after that shocking experience—but not Foley. Even though he returned home a public figure with a desk job as an editor with a Boston news agency, it didn’t hold him. In the end he flew out to a situation even worse than Libya. In 2012 that he went to Syria, only to be abducted once more months later. He would be held in captivity for two years, and it would end in his death.

The 2014 CWR article quotes from a letter Foley wrote to his alma mater, Marquette University, following his Libyan release. In it, his Catholic faith, and the part it played in his survival, is made explicit. There is no hint of any equivocation—Foley describes reciting the Rosary with a fellow hostage and, perhaps more importantly, what that meant to those then held prisoner. Yet the film mentions none of this. Instead, it hints that he converted to Islam at this juncture. Given what he wrote subsequently, it is hard to marry what he said then with this alleged earlier “conversion.”

The film is equally confusing about whether Foley converted to Islam in the hell created by his ISIS captors. One of his fellow hostages is adamant that he did. Others are more circumspect. All agree that Foley was a man of deep faith. Some go further and say that his faith was a link to home and family, especially to his mother. Converting to Islam, given the express and heartfelt Catholicism of the Foley family, would appear a strange choice; but it is with this possibility that the filmmakers leave the audience.

It could be argued that the filmmakers have tried to present a balanced view on a subject that they knew would be controversial—hence the inclusion of contributions from different hostages with differing opinions—but this leaves a muddled picture of what did or didn’t, might or might not have happened with regard to Foley’s alleged conversion to Islam. No doubt, this is yet another source of pain to his family; it also makes the film, in the end, depressing. What we are left with is a confused conclusion about Foley’s faith, made more forlorn as some of the last images on screen are those of the hideous execution—thankfully, its full footage is not included in the film.

This is, essentially, a hard film to watch. Ultimately, for Catholics, the film asks the troubling question: would you be able to keep faith if confronted by such dark forces in circumstances almost unimaginable in their terrors? After watching Jim: The James Foley Story, for such strength, one can only hope and pray.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.