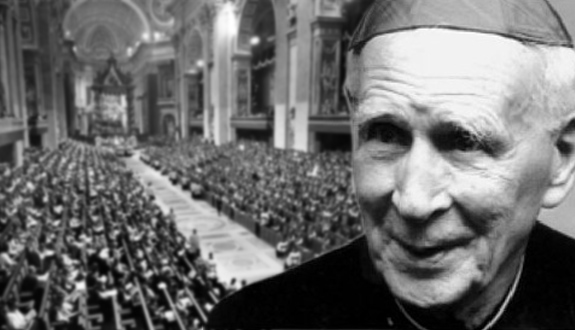

Last year I had the pleasure of reading and reporting to our readers on the first volume of Henri de Lubac’s memoirs of the Second Vatican Council. With the appearance of the second volume, I am now pleased to repeat the performance. We find the very same precision of thought and meticulous attention to detail in this volume as we found in the first. This time around, it might be helpful to consider de Lubac’s entries from three perspectives: doctrinal issues, the “atmospheric conditions” at the Council, and the dramatis personae.

Doctrinal Issues

Although the primary focus of the Second Vatican Council was not to be dogmatic (as envisioned by Pope John XXIII), there would be doctrinal components, to be sure. After all, pastoral theology is (or ought to be) the fleshing out of doctrine and morality into lived categories. And so, not surprisingly, the debates (indeed, the battles) among the theologians and among the bishops themselves did revolve around doctrinal issues.

One of the first issues to surface was whether or not the Council should produce a document on the Blessed Virgin Mary. This may seem like rather a “no-brainer” – who would oppose such a decree? The difficulty did not lie in the concept of a document as much as it did in who was proposing it and with what content in mind. Many of the more “traditional” or “conservative” bishops and their periti (theological advisors/experts) leaned heavily toward a “maximist” view of Mariology: “De Maria, numquam satis” (Never enough about Mary). Not a few of them also wanted to take aspects of Marian piety and enshrine them into dogmatic positions (e.g., Mary as mediatrix of all graces or co-redemptrix). Such a prospect was anathema to the more progressive wing of the Council, who did not even want a Marian document at all.

That wing prevailed. However, it was decided that a Marian element would be incorporated into the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church as the eighth and final chapter of Lumen Gentium. The logic behind this compromise was that if consideration ought to be given to Our Lady, it would be precisely as a member of the Church, indeed, the preeminent member of the Church. de Lubac was quite comfortable with that resolution. As it turned out, this was both providential and Solomonic as it gave a genuine theological grounding to the topic (rescuing Mariology from a hyper-pietism and serious excesses) and thus ensured a genuine future for a healthy Mariology, which has even had a positive influence on Protestant communities. At conclusion of the third session, Pope Paul VI took this solid development as the occasion to proclaim Mary “Mother of the Church.”

The whole question of religious liberty initially was to be handled within the document on ecumenism. In other words, the Church’s reflection on an ecumenical and political hot potato would be dealt with in the context of improving relations with other churches and ecclesial communities. The Council Fathers exhibited a willingness to acknowledge that new situations might call for new solutions. As is generally well known, the bishops from the United States were in the forefront of this cause, with the theological bolstering coming from Jesuit Father John Courtney Murray, whom de Lubac respected. The bishops of Eastern Europe saw the need for religious liberty and the rights of conscience to be respected due to their experience of decades of oppression from atheistic Communism. Another reason for granting some opening to religious liberty was not to “provoke persecutions” (19) in countries where Catholics were a minority. It was eventually decided that the topic should stand alone in what became the Declaration on Religious Liberty (Dignitatis Humanae), which was fiercely opposed by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre and remains a neuralgic issue for the Society of St. Pius X.

In June 1964, de Lubac read Jean Honoré’s Spiritual Journey of Newman (Honoré was made a cardinal in the “Newman” consistory of 2001, the bicentennial of Newman’s birth); two passages struck him with particular force.

From 1877:

As to the prospects of the Church, as to which you ask my opinion, you know old men are generally desponding – but my apprehensions are not new, but above 50 years standing. I have all that time thought that a time of wide-spread infidelity was coming, and through all those years the waters have in fact been rising as a deluge. I look for the time, after my life, when only the tops of the mountains will be seen like islands in the waste of waters. I speak principally of the Protestant world – but great actions and successes must be achieved by the Catholic leaders, great wisdom as well as courage must be given them from on high, if Holy Church is to (be) kept safe from this awful calamity, and, though any trial which came upon her would but be temporary, it may be fierce in the extreme while it lasts.

And then from the same time period: “When I see a clever and thoughtful young man, I feel a kind of awe and even terror in thinking of his future. How will he be able to stand against the intellectual flood that is setting in against Christianity?”

De Lubac’s comment? “This great fact perceived by Newman should be the main concern occupying the council” (124). Unfortunately, it was not. Bishop Marcos McGrath (born in the United States but named Archbishop of Panama City) noted already that “there has been a great misuse of the word ‘pastoral’” (216).

Regarding an “openness to the world,” “that has spread today in the Church,” he asserts that it “will cause a confused attitude that will no longer permit us to [speak] with as much certainty and truth. . .” (124).

One of the “first fruits” of the Council was the establishment of a theological journal, Concilium, intended to promote the Council’s vision and agenda. Many of the periti were part of that project, including de Lubac. By October 1964, however, he feels compelled to write a private letter to Jesuit Father Karl Rahner, the editor-in-chief, indicating his intention to resign from its editorial committee. He indicates that he is “greatly troubled” by the direction taken, especially with a recent contribution by Dominican Father Edward Schillebeeckx. A month later, de Lubac attends one of Schillebeeckx’s lectures and concludes that the man is “vigorous, very radical, totally lacking in nuance, stirring up and exciting a public that it would be more advisable to educate and calm. . . . He has a great power of conviction, but with something violent about it and without anything to reveal interiority” (294). In his formal letter of resignation a year later, he refers to Concilium as “a propaganda tool in the service of an extremist school” (355).

He notes that a Mexican bishop “complained of theologians who allow themselves to advance personal opinions whereas their role consists in showing the scriptural and traditional foundations of the Church’s teaching.” de Lubac perceived that this charge was largely “aimed at Häring” (245). Redemptorist Father Bernard Häring, to his dying day in 1998, dissented from Humanae Vitae. De Lubac also notes that “several moralists seem to me strongly inclined to laxism” (304). He also decries “a kind of collective amnesia” and the promotion of a “lawless freedom.”

de Lubac was concerned that the Gospel is “reduced to a social doctrine. . . the rest, not denied, but considered to be abstractions” (328). He opined: “Some want the council to speak about everything – except Christian revelation” (335), leading the Church “into a small worldliness” (326). He identifies the “Belgian Party” as particularly problematic and also the Jesuits (to whom he belonged). He speaks of “the cynicism of a program that considers nonexistent all the doctrinal, spiritual, and apostolic parts of the council and that involve us in paths of a miserable secularization” (425).

As we conclude our rehearsal of doctrinal matters, we can see that our raconteur was deeply troubled by a force within the Council that either ignored traditional doctrine and morality or so framed it as to make it innocuous.

Atmospheric Conditions

The doctrinal haziness, of course, did not emerge full-blown from the brow of Zeus; it was cultivated by various individuals and groups. Thus, at the outset of the second session, a speaker “reminded us that we are at an ecumenical council, not a circus” (24). Signs of the beginnings of a “media council” began to appear, whereby reporters were fed disinformation or at least highly “spun” information, so much so that de Lubac feels obliged to call it “organized propaganda” (34), largely orchestrated by French media and priests (in France, for example, there was already talk of married priests in the Western church). The disinformation efforts were designed to arouse episcopal sentiment against the Curia (i.e., against orthodoxy).

A prime mover of “spin doctoring” was Xavier Rynne, the nom de plume of the American Redemptorist Father Francis X. Murphy, whom de Lubac characterizes as “ever caustic.” de Lubac complains that the journalists, by and large, were “rather poorly informed,” looking for “disputes or intrigues, which they exaggerate and distort” (278). In the States, “Xavier Rynne” became the Fifth Gospel—for some, the First Gospel—for conciliar commentary.

Then-Bishop John Wright of Pittsburgh (and later, Cardinal Prefect of the Congregation of the Clergy) commented to de Lubac: “The bishops from now on must speak, explain, supervise; otherwise, they will be quickly snowed under by false commentators” (174). Once more, that counsel was not followed.

De Lubac recalls “an inside introduction to the inner life of the Curia,” conducted by a priest who determined that “a total, radical reform to be impossible” (42). The then-Father General of the Jesuits thought such a project “essential” and that Paul VI was better equipped to do the job than John XXIII. Apparently, Paul VI was not up to the task, nor John Paul II, nor Benedict XVI, causing one to ponder why Francis thinks he is.

Drawing a lesson from Catholic Action in France, de Lubac noted: “I am also trying to show [the bishops] the danger of a certain professional ‘laity’ that would create a screen between them and the whole of the Christian people” (174). Twenty years later, John Paul II would decry the clericalization of the laity and the laicization of the clergy. Early on, de Lubac realized that the German theologians and journalists were “easily attracted to extremism” (25).

Equally early in the conciliar process, it is reported that many bishops and theologians expressed a desire for the Pope to intervene, to which interventions he allegedly replied: “Things are not going badly enough yet!” (26).

Still another factor in the overall equation were the ethnic and ecumenical balancing acts. For instance, when the Ukrainian bishops organized a liturgy in honor of St. Josaphat, presided over by Pope Paul, two Russian Orthodox observers “spoke of leaving Rome” (46). Or, a presentation on the Catholic-Muslim dialogue held at the Angelicum University was so carefully orchestrated, so as not to cause offense, that de Lubac deemed it “disappointing” and “ultra-superficial” (47).

Similarly, the debate on Jews and other non-Christians raised concerns by bishops from Arab lands of retaliation and by Eastern bishops from dioceses where they were a minority (132). The push by the U.S. bishops for the declaration on the Jews gave rise to some dark humor: “Tomorrow, at the council, there will be a great ceremony; all the American bishops will stand in the central aisle, before the altar, and then their circumcision will take place – unless, upon verification, the operation had already taken place” (141).

As noted in comments on the first volume of these memoirs, de Lubac continued to advocate for the “Teilhard agenda”; most interesting, however, is that Father Stefano Minelli (founder of the Franciscans of the Immaculate, under papal scrutiny presently, presumably because of their traditionalist tendencies) would have “pestered” de Lubac for an Italian translation of his book on Chardin (223).

Our commentator rues the fact that philosophy, even in Catholic universities, was already in a shambles and that Christianity was not taken seriously. He is speaking of Europe here; it would take the United States a few more years to catch up.

The future cardinal bemoans the rigidity and arbitrariness of pre-conciliar discipline (signs of “decadence”) and then the opposite extreme whereby “today, everyone can, in private or in public, orally or in writing, inside or outside institutions of study, maintain any doctrine whatever, undermine the faith, contest the very idea of faith, without any superior intervening … Where are these inconsistencies leading us?” – asks a man who had suffered from the heavy hand of Rome, who concludes, nonetheless, that we are witnessing “growing anarchy” (100).

In a letter to philosopher Jacques Maritain, while expressing respect for Jews and Judaism, he nonetheless admitted that “I have a little difficulty in understanding fully the demands from some Jewish quarters, which seem almost to want to dictate to the council what the expression of the Christian faith should be” (122).

De Lubac observed that the translators of episcopal interventions were “not always very objective” (224). He also complained about the very loose translation of the liturgy in French, causing one to wonder: what would he have said about the English text?

There was much consternation over the text on marriage and the family (Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose!). Ottaviani made an intervention as the eleventh child of twelve. de Lubac (remember, no “fan” of Ottaviani) comments: “The personal, simple, touching tone, delivered with conviction by Ottaviani, made a strong impression” (236).

He reports a growing hostility toward Paul VI as the Pope felt compelled to intervene with greater frequency: “He would be praised if he would consent to say nothing and let everything go” (261). De Lubac likewise condemns the colonialism we encounter yet today: “The German bishops impose upon the South Americans, whom they hold by means of money” (299). Today that is attempted with the Africans as well—or worse, someone like Cardinal Walter Kasper in the two synods on marriage and the family simply dismissed the Africans as of no account.

The unraveling begins to gallop in 1965: “Several experts spoke of excesses that are spreading in the liturgy, of liberties that various preachers or seminary professors are taking with respect to dogmas, etc.” (319). In October 1965, he could remark: “There is a great deal of difference between the situation of today and that of 1962” (380).

Dramatis Personae

Our commentator had an uncanny appreciation of people. His “takes” on the various players during Vatican II proved to be unbelievably accurate in the aftermath. Let me simply present his comments on some of the cast of characters.

Bernard Häring: “ever intrepid for the cause of a liberal Gospel” (13); characterized by “a certain obstinacy” (71); his moral theology “does not take the objective order into account,” “speaks only of love” (91). Interestingly, this same dissenting theologian was recently praised by Pope Francis.

On the French bishops: They “lack clarity” (26) and are heavily influenced by bad priests. Which leads him to ask: “I wonder why our bishops let themselves be surrounded and circumvented by such men” (50). Further, he accuses them of gross arrogance (exhibiting no self-critical introspection), although a “grave crisis of faith that is rampant in France.” Even more pointedly, they suffer from “provincialism” and are “hotheads.” With brutal honesty, this Frenchman accuses his national hierarchy: “Miserable French ‘spirit’: cocky, petty, despicably anticlerical, desecrating and corrupting everything” (386). All of which makes one recall John Paul II’s searing question at the outset of his 1980 pastoral visit to the country: “France, eldest daughter of the Church, what have you done with your baptism?”

On the other hand, he had a uniformly positive attitude toward the ecumenical monastic community of Taizé. To those who regarded Cardinal Ottaviani as irremediably unecumenical and retrograde, de Lubac recounts that Ottaviani invited Brother Roger (founder of Taizé and an observer at the Council) to “visit his work with orphans” in Trastevere and to attend Sunday Mass. Roger asked de Lubac if he should accept the invitations, who advised him to do so – and he did. It would seem that de Lubac saw that community as very sincere believers, deserving of being taken seriously.

De Lubac seems to grow in his appreciation of Ottaviani and sees that he was not a totally closed individual, indeed, that he was open to good forms of what would later be called “inculturation” (as evidenced in his judgments on Japanese Catholic affairs).

Oscar Cullmann (Lutheran scholar) surfaces regularly and is esteemed by de Lubac as a good counter-weight to the biblical excesses of Bultmann. Lukas Vischer, Swiss Reformed theologian and official of the World Council of Churches, on the other hand, he deems “bad-tempered,” critical of papal policies; “always curt and disagreeable; doctrinaire spirit in what one senses is basically an anti-Roman fanaticism” (304).

On Pastor Marc Boegner, also of the Reformed tradition, he recalls that the theologian wrote to Paul VI, upset with the Pope’s negative comment about Protestantism: “I cannot keep from thinking, to myself, that these good Protestants are very sensitive. It is only too certain that Protestant, anti-Catholic influences are at work today in the Church and that the duty of the Pope and bishops is to guard against them” (268).

Any time that Joseph Ratzinger is mentioned, it is in praise of his “excellent” work. Helder Camara (later becoming the “poster child” for what would become liberation theology), he considered “generous, charming, profoundly evangelical; a little simplistic” (48).

On Cardinal Leo Suenens, he assesses a conference of his as being without any substance. During the final session of the Council, Suenens approached de Lubac for support in his writing a book, “The Virgin Mary, Birth Control, and Women’s Convents” – quite a conglomeration of topics, causing de Lubac to say: “I cannot help having the impression of a superficial, pretentious mind and of great self-satisfaction” (376). Regrettably, Suenens did produce the work on women religious, which helped destroy female religious life in the United States.

In somewhat coy fashion, he shares an impression of an intervention on religious liberty by Cardinal Richard Cushing of Boston: “thundering voice,” “applauded – perhaps because of his picturesque affability, in a rather ironic sympathy rather than with the seriousness of a substantive approval” (121).

Americans of a particular generation will be surprised by his evaluation of Bishop Fulton Sheen, “who spoke in an affected way, like a preacher at an 11 o’clock Mass; he was applauded..” He adds: “The substance of his speech was slight” (258).

De Lubac was often at odds with the Dutch Jesuit Father Sebastian Tromp, generally regarded as a ghost-writer of Pius XII (e.g., Mystici Corporis), the right-hand man of Cardinal Ottaviani, and regularly pilloried by proponents of less-than-orthodox views (in much the same way as Cardinal Ratzinger was attacked in lieu of John Paul II). Nevertheless, Tromp was able to make a careful distinction: “The declarations of this council are not absolutely dogmatic” (215). Interestingly, it took 51 years for that comment to become common currency in conversations with the SSPX.

That said, during the last session, de Lubac regrets that Tromp has “buried [himself] in a stubborn opposition to any renewal, which has given a revolutionary appearance to the first acts of the council, and since then, has facilitated paraconciliar disorder” (357). In other words, by refusing to allow for any genuine development, Tromp and others like him gave credibility to radicals who accused them of being frozen in an unchangeable past.

Cardinal Eugene Tisserant, dean of the College of Cardinals and a member of the board of the presidency of the Council admitted to being “bored” by the Council and allegedly summed it all up as “four hours lost every day” (308)!

Reacting to a 1965 article by Hans Küng, de Lubac calls it “incendiary, superficial and polemical” (309). Further: “An article calculated to appeal to public opinion, threatening and full of arrogance” (310).

He regrets the absence of Hans Urs VonBalthasar, who was never invited to participate in the Council. He muses: “How useful he would have been! The Church has in this way deprived herself of the best of her theologians” (410).

He delights in a humorous anecdote circulating around the Council: A priest had difficulty getting clearance from the Holy Office to publish a study; he was advised: “Ask the permission you need from Sister Pasqualina!” (414), the gate-keeper of Pius XII (La Popessa) and still apparently a mover and shaker nearly a decade after Pius’ death!

During the first session, he mentions a Polish bishop, who “spoke in a reasonable, Christian way” (126). That bishop was none other than Karol Woytyla (the future John Paul II). In the third session, he developed a deep respect and affection for that man who was “filled with a profound Christian sense” (321); who, in turn, asked him to write the preface to the French edition of his Love and Responsibility. At the end of the Council, he was moved by what he thought would be his last encounter with “the Polish bishop”: “Archbishop Woytyla embraced me. He has sensed our profound union in faith. I take away a keen memory of several of his interventions (he was too little listened to) and of our excessively quick conversations” (353). As a matter of fact, the high regard was mutual and de Lubac would encounter John Paul II again in 1983 when Papa Woytyla conferred on him the cardinal’s biretta.

In the final days of the Council, de Lubac was invited to lunch with Paul VI, who was effusive in his praise of the theologian’s work and fidelity—an experience not unlike that of Fulton Sheen who received the adulation of John Paul during his 1979 pastoral visit to New York.

As one who “grew up” during the Council and who suffered through the unmitigated post-conciliar melt-down in the seminary and my first years as a priest, I found the Cardinal-theologian’s commentary eerily prescient. The volume concludes with the conviction of “the necessity of basing aggiornamento on the two great dogmatic constitutions [Lumen Gentium and Dei Verbum]” (434). Surely, that was the conviction of both John Paul II and Benedict XVI. It seems that Pope Francis has opted for the “pastoral” approach cautioned against by Archbishop McGrath in the very first session.

Vatican Council Notebooks (Volume Two)

by Henri de Lubac

Ignatius Press, 2016

Paperback, 536 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.