Editor’s note: This is the second of a series of reviews and essays—positive, critical, and mixed—of Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option (Sentinel, 2017). Read the first essay here.

With the publication of La Primauté du spirituel, in 1927, the French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain initiated his decades-long argument in favor of a modern Christian politics rooted in a few striking claims. The modern West, with its supposed Christian political order, had long since been hollowed out by secularism. Christianity itself was marred not just by sin but insincerity: the civil religion to which it had been reduced was no longer even able to sustain a unified political order. The living political tendency of the age was toward a disintegrative secularity and pluralism, and this was finding expression primarily in liberal democracy.

Liberal democracy had, in its favor, the virtue of proclaiming the freedom and equality of men, which was, not incidentally, a revealed truth of Christianity. All human persons are wholes ordered to the whole that is God himself even as they are also parts of society; every just politics will take this “personalist” truth into account. And yet, despite this genuine intuition, liberal democracy had by nature a narrow view of this truth and so conceived freedom and equality not in spiritual but “anthropocentric,” willful, and material terms.

Maritain proposed that this tendency toward secular liberal democracy, because rooted (however imperfectly) in the truth about the human person, should be embraced. The old Christendom of a religiously unified West that gave juridical expression to God’s sovereignty over the world, was, for the time being, out of reach. But, a new Christendom could be brought about—provided, that is, Christians recognized a handful of principles about human nature. First, the font of Christian life is prayer and so the supernatural or infused contemplation of the Christian must serve as the cornerstone not only of each person’s ecclesial life but of political life. In recognizing that, in the contemplation of God, the human person fulfills his destiny to know the truth and attains to a genuine freedom and equality that transcends his role as a part of temporal society, the Christian perceives the true dignity of the person. “A renewal of the social order on Christian lines will be a work of sanctity or it will not occur at all,” Maritain warned.

It is the Gospel that proclaims this truth about man, and so, second, political society must be reformed according to a “Gospel inspiration,” by which Maritain intended that liberal society be so ordered as to respect and aid the ordination of the human person to the contemplative life whose perfection lay in the Kingdom of God. A secular and pluralist order could recognize, accept, and govern itself in response to this truth about human nature. Even if it did not recognize the specific transcendent destiny of the person to life in Christ, its vision of freedom and equality was nonetheless rooted in an intuition of the human person’s having some such destiny. Maritain’s proposal was rooted in a prudent vision of what seemed possible for modern political life as well as in an undeviating vision of the source and dignity of the human person in the triune personhood of God.

How was it greeted? By those on the right, he was deemed a capitulator and heretic, who wanted not to bring about a “new Christendom” but an altogether “new Christianity” (a willful mistranslation of Maritain’s French). By those on the left, he was met with curious fascination rather than actual engagement.

In good time, however, his ideas would win out where it mattered most. Maritain’s proposals found authoritative expression in the social encyclicals of Paul VI, and his term “integral” (as opposed to “anthropocentric”) humanism remains the standard for Catholic teaching on human development to this day. His position would also find expression in the United Nations, and in the Christian Democratic parties of western European states in the decades to come, where “social democracy” was intended to create living conditions that would, in Maritain’s words, equip each citizen for the life of reason. In Latin America, Maritain would become a prophet of a corporatist democratic vision embraced by multiple regimes.

As we all know, however, even where Maritain best succeeded he finally lost. The West may have nodded toward the “Gospel inspiration” that justified liberal democracy, but on the whole it ignored Maritain’s admonition that political life must categorically be rooted in a restoration of contemplative life. Social democracy in Europe appears more like the management of gradual decline for a civilization that has lost its sense of purpose than it does a regime committed to helping each person realize his spiritual destiny. Latin America continues to veer unstably between right and left wing regimes neither of which seems especially committed to advancing the truth about human nature.

Maritain tried to teach liberal democracy that the human person merited freedom and equality because he was ordered by reason to know the truth. He did not perceive that it was less out of mere ignorance than by positive decision that liberal society proposed something contrary: the person is valuable only insofar as he can impose his manufactured truth on the world by force of will and make something good for the satisfaction of his own desires. Ordination of the person to the contemplation of truth, in liberal eyes, appears positively grotesque and is deemed in any case an impediment to man’s equal-freedom to exercise his will whatever way he sees fit.

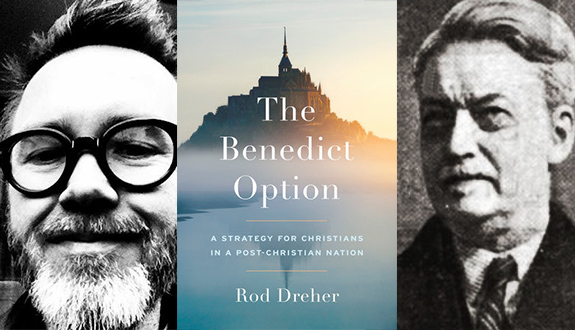

And so, here in 2017, the writer Rod Dreher, has published The Benedict Option, proposing that liberal democracy has become too hostile to Christianity to acknowledge, much less respect, any “Gospel inspiration.” Social life in the West has already become post-Christian. In a concise but convincing potted history, Dreher proposes that the modern age has become “liquid,” as it deems the world neither true nor good in itself, but as raw material to be made true and good as we impose our ideas upon it by force of will (abetted of course by advanced technology). Those Christians who would not surrender entirely to a political order that is fundamentally nominalist, voluntarist, individualistic, hedonistic, and technocratic, must themselves rediscover a deep devotion to Christ and find ways to live out their social and political life in conformity to the fundamental personal act of prayer.

“If Christians today do not stand firm on the rock of sacred order as revealed in our holy tradition” Dreher writes, “we will have nothing to stand on at all. If we don’t take on everyday practices that keep that sacred order present to ourselves, our families, and our communities, we are going to lose it.” He concludes that Christians must undertake “the long and patient work of reclaiming the real world from the artifice, alienation, and atomization of modern life,” by reimagining their way of life in a loose analogy to the way of life of the historical Benedictine orders, who built their communities not primarily out of stone and cloister, but out of a rule ordering them to a shared life of prayer and work.

And how has Dreher’s proposal been greeted? By the right, he has been greeted by many as a capitulator and heretic who would have us surrender our hopes for a restored Old Christendom and beat a path for the hills. By many on the left, he seems to be viewed as an odd curiosity whose “alarmism” is deemed misguided and unnecessary even as they unreflectively insist on rooting out every trace of “Gospel inspiration” from the liberal democratic spirit so as to replace a “personalist” or humanistic order with a technocratic one that panders to the basest hedonistic and acquisitive instincts of our supposedly “fluid” and autonomous selves.

Just as Maritain was misunderstood at a time when real reform of the liberal order seemed necessary and likely, so has Dreher been misunderstood now, because so many of his readers misunderstand both what it means for man to be, in Aristotle’s words, a political animal, and how Dreher is suggesting we fulfill that nature in a hostile age.

Dreher’s proposal for “Benedict Option Christianity” takes its name—in my opinion, unfortunately—from the memorable closing paragraph of Alasdair MacIntyre’s now classic work of philosophical ethics, After Virtue (1981). There, MacIntyre writes of a “crucial turning point” during the early medieval “Dark Ages,”

when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium. What they set themselves to achieve instead—often not recognizing fully what they were doing—was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness . . . What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us.

To speak of an “option” normally means to speak of a free and deliberate choice, but this is not quite what MacIntyre intended. After Virtue argued that we need not appeal to Aristotle’s “metaphysical biology” in order to demonstrate that man is a political animal. It suffices merely to observe postmodern accounts of selfhood that say everything about the self is formed through the human person’s intrinsic location in community. Whatever the “essence” of human nature may be, we see that there is no human being outside a community and our selfhood is largely a creation of the culture and society of which we are a part.

The difference between a better or a worse society will be how well that culture is able to perceive and articulate a vision of the genuinely good human life and to make possible its attainment through the discernment and practice of those virtues necessary to such a life. In due time, MacIntyre would be convinced by Saint Thomas Aquinas that this purely social truth is vindicated by a study of human nature in all its depths (that “metaphysical biology”), but this was not strictly necessary to his argument.

Because the human condition is irreducibly a social one, we live out our lives politically. We seek out those persons, communities, and ways of life that we think will enable us to envision and realize a good life for ourselves. Just as water runs downhill and will make its way with a kind of cunning around any obstacle, so our social natures lead us to invest our time, concern, and sweat in whatever places or people we think will enable us to understand and secure our own proper good—happiness.

This is just what we do. We find ourselves losing touch with one group of friends and find ourselves out with another, some Saturday afternoon, simply because one group’s company no longer quite attracts us, while another’s does. We join a club, an office, or a church, because we sense that participation in it will attain some good we require to be fully human. Or we drop out and withdraw from Boy Scouts or bowling leagues, or whatever else, as we cease to sense that our participation has some good object worthy of our commitment. Modern loneliness is not a sign we are not social by nature but rather a symptom of our failing to find others capable of helping us to live well. Most of the time, of course, our investment of what you may call our political or cultural capital is not so black and white. We engage more with what seems better and engage somewhat less with what seems less valuable.

Dreher wishes to demonstrate that the mainstream of American life has become sufficiently corrupted that Christians’ investment of their cultural capital in political parties and elections is no longer the best way to use it. While institutional politics remains inevitable, because the American government will continue to rule us regardless of what we think about it, the dream of a Christian democratic society, however attenuated, is for now out of reach.

The worst instinct of liberal democracy, its elevation of the expression of the individual human will to the one remaining sacred good, has thoroughly triumphed. It has reformed from within Christian and religious life along the lines of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism (MTD), where religion is reduced to a therapeutic servicing of our sense of “well being.” It has formed society most prominently through the sexual revolution, where fertility, monogamy, marriage, and now the distinction between man and woman are all to be redefined to conform to whatever so-and-so happens to desire today. Less obviously, but no less consequentially, it has transformed how we educate our children (to acquire means to exercise their will rather than to know what is true, good, and beautiful); how we spend our time (consuming blue light from screens); how we interact with one another (poorly); and how we interact with the natural world (with a mixture of avarice and guilt and seldom with a sense that we are a good part of it ordained to its just rule).

Whether we approve these changes or see them as diabolical, we are part of the society in which they are taking place. Should Christians seek to shore up or gain control of the mechanisms of power of that society? Will that better enable them to practice a good way of life and pass it on to their children and grandchildren? Or is it rather the case that the liberal order has advanced so far in its secular voluntarism that we would better spend our lives entering more consciously into our religious practices, seeking to deepen and renew them all the better to resist their deformation by the corrupt fancies of our age?

Dreher’s answer to these questions is a qualified one. Because orthodox Christians are intrinsically a part of the broader society, they have no choice but to influence its institutional life as best they can, but the forces arrayed against them are rich, formidable, and bloodthirsty. The Christian right has largely failed to redirect our culture after forty years of trying; we will be fortunate now to hold the opposition at bay—and this we must do. Dreher sees, rightly, that the powerful “liquid” liberalism of our age would not be so great if Christians had more truly rallied to Maritain’s vision nearly a century ago to purify the sources of our religious devotion and to renew our political lives so that they conform to and aid our vocation to the knowledge and love of God. Because the times are less propitious now, Dreher summons us to follow the example of the Benedictines, to conceive of new “rules” or disciplines by which we may live so that our days are shaped primarily by our perception of God as our good rather than by the fluid, insidious influences of the mainstream culture.

Which rule, exactly? Answering that question is one of the delights of Dreher’s book, as he takes up his journalist’s mantle and goes traveling to interview various groups of Christians in America and Europe to learn how they are keeping alive the faith amid contemporary indifference and hostility. In sharing their experiences, he offers to the reader suggestions as to how we might live our Christian vocations more deliberately so as to build up communities that seek what is truly good and which school us in the virtues we need to attain it.

Again, seeking just such communities is what we political animals do by nature, but we do not usually do it consciously and we do not always do it well. Dreher’s “Benedict Option” is therefore not a suggestion that we withdraw from political life, but rather that we live out our political natures even more fully, variously, and consciously, by seeking to build up those moral communities that will actually help us to become, in Maritain’s words, ever more fully human. Trips to the ballot box always played a small role in our political life, but the sooner we realize how small that role really is, the sooner Christians will discover how many different strands of political life require our care so that the faith may endure even into the next generation. Dreher reminds us in a more desperate language of what Maritain reminded us long ago and with whose words I would leave you:

There is for the Christian community, at a time like ours, two opposite dangers: the danger of seeking sanctity only in the desert, and the danger of forgetting the necessity of the desert for sanctity . . . Christian heroism has not the same sources as other heroisms; it proceeds from the heart of a God scourged and ridiculed, crucified outside the gates of the city

The Benedict Option

by Rod Dreher

Sentinel, 2017

Hardcover, 262 pp.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply