“Of course I am disappointed. By the continued existence of lack of interest in the Church. By the fact that secularity continues to assert its independence and to develop in forms that increasingly lead people away from the faith. By the fact that the overall trend of our time continues to go against the Church.” – Pope Benedict XVI, Light of the World, 2010.

“In celluloid we trust.” – Werner Herzog, The White Diamond, 2004.

Imagine an autumn Saturday night in 1965. The Agony and the Ecstasy is playing at a local, one-screen theatre. A family of four takes in the show. The next morning, the very same family tailored in their Sunday best attends their local parish along with other members of the town community, some of whom they noticed at the movie house the previous night. They discuss the picture after Mass, agreeing that while they enjoyed seeing the Renaissance and Michelangelo depicted on screen, it was not one of Hollywood’s better epics. Later that day, the family takes a drive in the country to see the changing leaves. With businesses closed on Sundays, there is little traffic on the roads. There is a quiet peace. Likely unconsciously, this family basks in living with clean consciences, spurred not only by church that morning, but in the entertainment value provided the previous night.

This keeping-holy-the-Sabbath-day-scenario is not intended as Norman Rockwell idyllicism, but a snapshot of the life of many throughout American history: hard-working people embracing the fortifying pillars of a successful civilization—family, faith, and mutual ethics.

Cultural and cinematic change

Yet by the time of its release, October 1965, The Agony and the Ecstasy showed a Hollywood sagging. The sword-and-sandals pictures and Biblical epics of the 1950s had culminated with Ben-Hur’s 11 Oscar wins. The 1960s attempted to continue the formula, but El Cid, Cleopatra, and The Fall of the Roman Empire proved the thrill was gone. By the time Charlton Heston climbed the scaffold of the Sistine Chapel, it was clear that change was in the air—social change and ethical change. The Second Vatican Council was two months from closing, the three year sessions arguably the imprimatur the world was waiting for to usher in a more relaxed new world order. With the abandonment of the motion pictures Hays Code, the content of movies also entered a new era.

If that same family ventured to the movie house five years after The Agony and the Ecstasy, they would find the likes of Love Story and Myra Breckinridge. The disconnect between culture and church had begun its devastating divorce. If one longed for the days of Bing Crosby as Fr. O’Malley, he or she would be hard pressed; new Hollywood had overtaken the crumbling studio system with brash abandon, bulldozing such sentiment out of its way. Rosemary’s Baby in 1968 gave way to The Exorcist and Jesus Christ Superstar in 1973. In 1972, Paul VI lamented that the smoke of Satan, from some fissure, had entered the temple of God. The assault was underway, and relativism was the new mantra of this Age of Aquarius.

A quiet underground toward this new age had been developing for decades. In 2006, the Getty Center in Los Angeles ran “Cinema of Grace,” a film series of art house classics by filmmakers Carl Theodor Dreyer (The Passion of Joan of Arc, 1928), Fritz Lang (Destiny, 1921), F.W. Murnau (Nosferatu, 1922), Robert Bresson (Diary of a Country Priest, 1951), and Werner Herzog, (Heart of Glass, 1976 and The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, 1974). “These directors depicted what they saw with their ‘spiritual eye,’ finding beauty, goodness, and the transcendent in what others might see as ugly and dark,” the event advertised.

As a film student at the time, I took no issue with this program lineup. I did not fully realize—or perhaps did not want to realize—that often such praises of the kind the Getty heaped on these works came at the expense of the tenets of faith. “Like other films in this series,” it touted for the 1951 Bresson adaptation of the Georges Bernanos novel, “Diary of a Country Priest is infused with a sense of the shallowness of everyday life and of the constraints of organized religion in the realm of the divine.” Healthy skepticism means lucid objectivity. Agnosticism means true faith. Human experience and articulating it—that is what matters. On Dreyer’s Joan of Arc: “The struggle between the material and the spiritual, between institutionalized religion and pure faith, is a common thread.” Yes, those who condemned Joan to the stake were hierarchical prelates. But Joan became the saint, not them. Yet, it did not occur to me to question any of this verbiage. For this was art! This was truth! I also find it no coincidence that I had not yet even known of the concept of relativism at that time.

Today, asking a family to enjoy a Saturday night taking in a wholesome Hollywood entertainment is near impossible: so natural and casual does a script call for blasphemy against the Second Person of the Trinity, littered with routine curse words, all while pornography melds into mainstream, it becomes startling clear: Nowhere here does God exist. “I fell away from you, my God, and in my youth I wandered too far from you, my true support,” lamented St. Augustine. “And I became a wasteland of myself.” But depicting that wasteland that is precisely what is considered art these days with maybe a glimmer of secular hope at the end, for wallowing and wasteland implies profundity and depth and meaning. The God learned in second grade has long been packed away. Tragically, so many artists unconsciously steeped in the Catholic imagination as youths have not yet had a mature encounter of that God. Such an encounter was a frightening prospect. “Christ is an abyss of light,” Kafka warned a friend, “into which, unless you close your eyes, you will fall headlong.”

Something was gnawing at me. This was a mentality spilling out not just in entertainment but commanding an entire worldview. It was the first time I felt nervous about the state of the faith—and felt some responsibility towards its preservation. Despite knowing that to some degree or another Martin Scorsese, Luis Buñuel, Francis Coppola, or Alfred Hitchcock continually dipped in the fountain of Catholicism in their films, I began to wonder how many of our heralded Catholic filmmakers could be found on their knees Sunday after Sunday before the consecrated host?

Art and faith

Should the personal beliefs of artists matter in contemplating their art? “I had a dramatic religious phase at the age of fourteen and converted to Catholicism,” Werner Herzog admitted in 2002. “Even though I am not a member of the Catholic Church any longer, to this day there seems to be something of a distant religious echo in some of my works.” Robert Bresson saw no distinction: “Must one look at the life of someone to judge his work? This is his work. And that is his life.” And Martin Scorsese has never been shy in expressing his youthful enrapture of pre-conciliar Catholicism before setting out on a career depicting characters struggling—consciously or not—with faith.

And so if the life and the work are intertwined, what messages are our artists sending? Is it that in order to be truly alive one must shrug off the shackle of faith, of orthodoxy? That thinking for oneself is the true path to enlightenment—without realizing such a notion is free will, and to reach enlightenment one cannot avoid the presence of Jesus Christ along the way, the very path being trod?

Witness relativism run rampant, its effects on relationships with each other, in communities, how we process and receive information as citizens; its effects on the Church, from customized liturgical styles to debatable and faddish beliefs, to no longer being able to discuss matters of the faith with peers without being found polemical or proselytizing; its effects on our brains, what we choose to watch; and on art itself. The most harrowing effect is the palpable absence of God in the world, as if experiments are conducted on our immortal souls to test their very immortality. Their destruction is possible, even for the pure of heart. “Do not tempt me! I dare not take it, not even to keep it safe, unused. The wish to yield it would be too great for my strength,” Gandalf admits to Frodo in The Fellowship of the Ring.

A theologian writing in the 1960s, seeing the seismic cultural shifts occurring, urged his students to hold fast the horizontal and verticals dimensions of the Cross—the divine and the human dimensions, the personal and the communal, the questioning and the confession of faith. “And if you do doubt,” the theologian advised, “etsi Deus daretur—believe as if God existed.” Later, he would say this, something Herzog and Scorsese and the Getty Center might contemplate: “[P]eople are afraid when someone says, ‘This is the truth,’ or even ‘I have the truth.’ We never have it; at best it has us.”

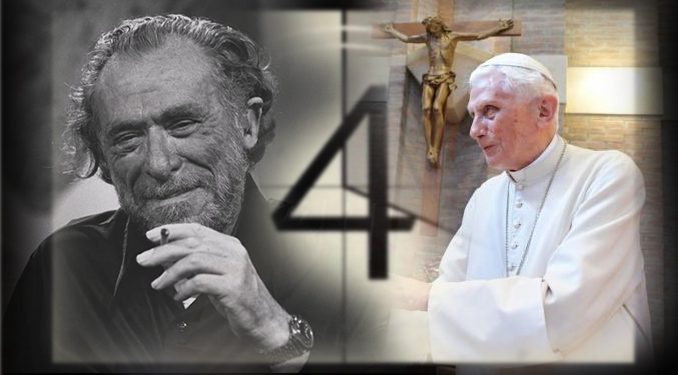

Pursuing the truth found in the ugly and dark, in the messy, also defined the underground lit scene of Los Angeles. “Ah Los Angeles! Dust and fog of your lonely streets, I am no longer lonely. Just you wait, all of you ghosts of this room, just you wait, because it will happen, as sure as there’s a God in heaven,” mused the main character in John Fante’s Ask the Dust. By the time Ask the Dust debuted in 1939, Fante had already established a life that would alternate between deeply personal writing and heavy drinking and gambling. He published his first short story at age 23, titled “Altar Boy.” Both Fante and later his protégé, Charles Bukowski, would halo those lonely streets of Los Angeles in their writing with depictions of the sordid real world as guided by alcoholism, of rotating women, and constant agitation, out of which came prolific odes to that world.

Cult fame would follow. Though raised Catholic, Bukowski eventually drifted. He evidently gravitated to Buddhism later in life. The idea of a lifelong postal worker turned writer, who embraced his own booziness and womanizing and acting as if beyond redemption, captivated many. “Food is good for the nerves and the spirit,” read a passage in his novel Post Office. “Courage comes from the belly—all else is desperation.”

I first read Bukowski during the last months of the life of another poet: John Paul II. “Church needs art. Does art need the church?” he asked in his 1999 “Letter to Artists.” But who by then was listening? Some, like Bukowski, choose to delve into agony. Others, at the risk of being labeled as puritanical, take the leap into the transcendent. A writer familiar with the trending atheism of Europe aptly identified the inner turmoil of its youth:

The dismal and destructive ecstasy of drugs, of hammering rhythms, noise, and drunkenness is confronted with a bright ecstasy of light, of joyful encounter in God’s sunshine. Let it not be said that this is only a momentary thing. Often it is so, no doubt. But it can also be a moment that brings about a lasting change and begins a journey.

Hidden in plain sight

This writer, the same who earlier was quoted about believing as if God existed and that we don’t have the truth, it has us, is Joseph Ratzinger—Benedict XVI. There he was, I discovered, hiding in plain sight as the then-bishop of Rome hurling down one masterpiece after another in his weekly audiences. And then something even more startling occurred: he evoked within me the same sense of awe and identification once felt with the masters of cinema. What did it mean that the successor of Peter, the vicar of Jesus Christ, would be the one who so perfectly articulated the malaise and acedia of our time? “Again and again man falls behind the faith and wants to be just himself again; he becomes a heathen in the most profound sense of the word. But again and again the divine presence becomes evident also. This is the struggle that passes through all of history.”

Of course, the great works of art indeed attempted to delve into the heathen world and the divine presence, but it was the expected tone of reproach that anything having to do with the Church must be undermined that I simply could no longer stand nor wanted to contribute in the attempt to destroy it. What continually frustrated me was how capable filmmakers and artists failed to realize that the story of faith in the world is the hard fought journey of the sinner to redemption—from one Gospel account after another of transformed, nameless sinners through Peter, Magdalene, Augustine, Ignatius, Chesterton, Dorothy Day, and the working class penitent who defies the standard of the day by hunkering down in the confessional and poring out his faults. Gradually, I grasped what I read the Pope himself voice:

Of course I am disappointed. By the continued existence of lack of interest in the Church. By the fact that secularity continues to assert its independence and to develop in forms that increasingly lead people away from the faith. By the fact that the overall trend of our time continues to go against the Church.

The effort of moving outside oneself, of making it to Mass, to carve out time amid what could have been far easier, more lackadaisical, relaxing weekend choices, was difficult with so much disposable attraction available. But the physical action of getting into that church itself said something. Benedict in 2006, speaking to journalists on the plane back to his Bavarian homeland, somehow understood this millennial stagnation. “I can continually do whatever I want with my life,” he stated, evoking the freedoms one has. “By making a definitive decision,” he continued, “am I not tying up my personal freedom and depriving myself of freedom of movement? Reawaken the courage to make definitive decisions: they are really the only ones that allow us to grow, to move ahead and to reach something great in life. Risk making this leap.”

While I remained indebted and committed to the truth of film, I gradually lost much interest in Werner Herzog and Jean-Luc Godard while still admiring their feats, some of which, like Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo and Godard’s Contempt, are pillars of filmmaking. I suppose I decided to be less like them and more my own person. This meant I now had a duty. I could no longer risk witnessing the withering of my own spiritual capacity, the precariousness of my own immortal soul. As Dorothy Day wrote, “I felt the need to go to church more often, to kneel, to bow my head in prayer.” Benedict XVI quoted this in his first Wednesday audience after announcing his intention to resign.

I still had no doubt film is able to reach into the transcendent, but I believed it only goes so far. The majority of cinema, reduced to crass entertainment, simply lacked the substantive push and desire that Benedict managed to prompt within me: to think about God and the world, who Jesus was and is, and our place within that Trinitarian circle of light that Dante dreamed. I began to see belief meant not a crutch to dogma, but an active, daily setting out, even especially during times of doubt and darkness. I went to confession more, and meanwhile consumed every available book by Benedict XVI.

When reading Benedict’s Jesus of Nazareth, and meeting Blaise Pascal in the process, I knew I reached a crossroads. Previously, my only recognition of the name Pascal (other than a vague memory about his famous “wager”) was Werner Herzog’s Lessons of Darkness, which opens with a quote attributed to Pascal: “The collapse of the stellar universe will occur—like creation—in grandiose splendor.” Of course it is well known in film lore that Herzog wrote that line himself, and gave it to Pascal because to him it was something Pascal would have said. That is an undeniably fabulous anecdote, but then one comes across the real Pascal, such as in his “Night of Fire” sequence at age 31 (1654) that resulted in sewing “The Memorial” into his jacket and immediately one realizes he is before a master.

His Pensées remains a touchstone of inspiration: “A fine state for the Church to be in when it has no support left but God!” (#845). Pensées also served as a precursor in style to Robert Bresson’s book, Notes on the Cinematographer. And it was Pascal who originated the line Ratzinger quoted in Introduction to Christianity: etsi Deus valetur: Believe as if God existed.

From Nouvelle Vague to the Nouvelle Theologie

Eventually, something had to give. It took much discernment, but soon many books and films of and by Godard, Herzog, Buñuel, Oliver Stone, Woody Allen, coupled with Bukowski and Fante and others made their way to the donation chest at the local library. Bresson remained. Not only was life too short, but I simply had to make room for Guardini, von Balthazar, Belloc, Pieper, Chesterton, de Lubac, Lewis, Tolkien, Dickens, let alone the von Hildebrands and Fulton Sheen and James Schall and Flannery O’Connor, Bernard Lewis’s studies on the Middle East, Fr. Robert Spitzer’s quartet, T.S. Eliot’s Christianity and Culture, and the unceasing outpouring of current minds from a Catholic perspective, such as Paul Scalia’s That Nothing May Be Lost. I took delight that Ratzinger’s The Spirit of the Liturgy in 2000 was a spiritual remake of Guardini’s own The Spirit of the Liturgy from 1918. I had seen this before—in film. The Nouvelle Vague had given way to the Nouvelle Theologie.

And while I certainly continue to admire great film and the struggles and triumphs of those who see their vision through, godly matters had proven far more edifying than mundane trivialities. Even in a time so secular, agnostic, and atheistic, and even when the Church sometimes seems more focused on the human than on the supernatural, the sacred was still visible and still worthy of pursuit. I immersed contemplatively in the music of des Prez and Respighi, gazed more appreciatively at the art over the centuries, the wonder of architecture, and gave thanks I had the opportunity by way of a faith pilgrimage to stand enveloped by Gaudí’s La Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. Gaudí, Benedict XVI said at that very spot in 2010, “accomplished one of the most important tasks of our times: overcoming the division between human consciousness and Christian consciousness, between living in this temporal world and being open to eternal life, between the beauty of things and God as beauty.” Little to nothing could be added to the truth of that insight.

Werner Herzog likes to tell this story:

After Michelangelo had finished the Pieta in Rome, one of the Medici family forced him to build a snowman in the garden of the family villa. He had no qualms about it; without a word he just went out and built the snowman. I like this attitude and feel there is something of absolute defiance in it.

If anything is certain in surveying modern culture, it is that the defiance Herzog speaks of in Michelangelo creating the snowman is needed for an artistic reclamation of this cynical world, to once again dare to glimpse the transcendent, or rather, the joyful encounter of God’s sunshine. Will the next Michelangelo or Dante please stand up?

In this age of remakes and reboots, it would be wonderful to see the triumph of the human condition portrayed in appropriate grandeur, but only with the authentic dignity toward the human person that once epitomized the art of the cinema, that lifted consciences, and actually inspired flocks of peoples from the theatre on Saturday to the pews on Sunday.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

A fine piece from one movie enthusiast to another; and one increasingly alienated from the craft and art. The Holy Father remains my lifeline and anchor in the Church. A much misunderstood Pope and, I believe, future Doctor of the Church.

Amen ; amen.

James, maybe you are the next Michelangelo or Dante!

Putting Bukowski anywhere near Benedict 16 in the same line may not be a sin, but somehow it just doesn’t seem right.

Have you read the article?

To believe as if God existed seems an anomaly. If we believe there shouldn’t be if. That shadow of doubt may reference Pascal’s realism. It reminds me of a line from Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu, when the vampire tells a woman of faith, “Faith! It’s the hope for what we know doesn’t exist”. Herzog a self proclaimed atheist could not extract himself from belief. In Nosferatu he portrays a victim surrounding himself with consecrated hosts as protection. Nexus. Faith in the modern world. Benedict XVI critiques loss of nexus between practice and salvation in an interview by Jacques Servais SJ. The question is salvation for the very many. Benedict assesses Rahner, “He sustains that the basic, essential act at the basis of Christian existence, decisive for salvation, in the transcendental structure of our consciousness, consists in the opening to the entirely Other, toward unity with God. The Christian faith would in this view cause to rise to consciousness what is structural in man as such. So when a man accepts himself in his essential being, he fulfills the essence of being a Christian without knowing what it is in a conceptual way. The Christian, therefore, coincides with the human and, in this sense, every man who accepts himself is a Christian even if he does not know it”. There is marked resemblance with the current definition of faith stemming from Jesuit minds including Pope Francis. That realization of self [as is] created in God’s image suffices. Benedict ever astute knows this. His insulated response is need for repeated confession.

A note on faith referenced in Pascal’s “Believe as if God existed”. Faith is best defined in simple terms as most profound truths are by The Apostle [although questioned most attribute Hebrews to Paul], “Faith is the realization [realization, hypostasis in Gk means substance] of what is hoped for and evidence of things not seen”(Hebrews 11:1). Spiritual evidence known by the intellect is superior to knowledge of physical things known thru the senses. That is why those who disbelieve are condemned not because of deficiency of knowledge, rather because of a decision not to believe. Pascal’s phrase may then be understood to mean Don’t simply believe [as one believes the sun will rise in the morn], have faith.

Maybe I didn’t read it close, but Bukowski? I just wonder if the author read Mickey Spillane.

He’s right. Modern artistic expression teaches us that we are doomed, brute beasts and that what we think of as hope is delusion.

A beautiful piece that resonated with me on so many levels.

As you enter the water of Benedict XVI’s writing you find yourself throwing previous attachments back to the shore, and eventually, without regret,casting them into the current to be taken away forever.

Thank God for Joseph Ratzinger.