Simon Leys: Navigator Between Worlds by Phillipe Paquet (La Trobe University Press, 2017. 664 pp.)

The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays by Simon Leys (New York Review of Books Classics, 2013. 572 pp.)

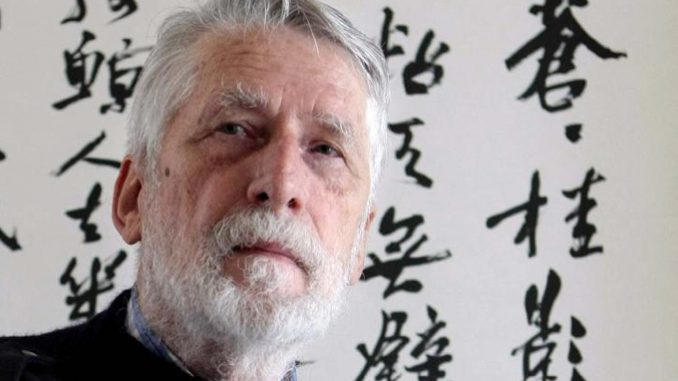

Simon Leys (1935-2014), born Pierre Rykmans, was perhaps the last Catholic man of letters. Born in Belgium, he received a traditional education and then studied law at the Catholic University in Louvain. However, he published most of his work in Chinese and English, and lived for much of his life outside of Europe, mostly in China, Hong Kong, or Australia, where he died in 2014. An acknowledged master of the art and history of Chinese calligraphy, Leys translated Chinese classics, including The Analects by Confucius, and he wrote widely on literature in several languages. In particular, his work on the sea in French literature is a classic. Phillipe Paquet has produced a well-researched biography that is a welcome introduction to a writer less well known in the United States than he should be, and a new collection of his essays illustrates Leys’ range and sparkling style.

Leys first came to prominence in the early 1970s with a book, titled The Chairman’s New Clothes, attacking the Mao-besotted among the European Left and revealing the Mao terror for what it was. It is perhaps difficult now to understand the adulation with which Mao was greeted by Western elites, especially academics who praised his “cultural revolution.” Leys, who had spent significant effort examining Mao’s reign, had little patience for such people. He was no reactionary, however; in the 1950s, he had some sympathy for the Chinese Communists, when he visited along with a delegation of Belgians in 1955, and he remained in some sense a man of the Left. The intervening years, however (which he had spent in Singapore and then Hong Kong), changed his outlook. This change was due to several factors, not least of which were news reports collected by a Jesuit in Hong Kong that were more truthful about what was happening in Mao’s China than Western reports had been. In an essay written in 1981, he excoriates the “China Experts” who either ignored the atrocities being committed in China or thought that such barbarism fit the “Chinese character.” At the time of publication, Leys was working for the Belgian embassy in China, and so needed a nom de plume to provide cover; the one eventually chosen echoed the protagonist of a Belgian novel about China—René Leys—combined with Simon, after Peter. Once the book was published, and Leys returned to China in early 1972, his suspicions were confirmed. Upon seeing the Chinese capital again, he wrote, “One thing is certain: despite all it has done, the name of the regime will also be linked with the outrage it inflicted on a cultural legacy of all mankind: the destruction of the city of Peking.”

Leys spent his career arguing for the truth, and for the existence of objective values—artistic, cultural, and moral—and against imposture and ideology. In 1977, he wrote that “culture alone, in the deepest meaning of the word, can ultimately justify the human endeavor.” This was the main reason Leys argued against Maoism and its Western supporters. The Maoist ideology was destroying the Chinese culture that he loved, indeed valued so highly he thought Europeans should place it alongside Latin and Greek as an object of cultural and linguistic study. The study of Chinese culture, he thought, was the greatest antidote to cultural chauvinism. “From the great Jesuit scholars of the 16th century down to the best sinologists of today, we can see that there was never a more powerful antidote to the temptation of Western ethnocentrism than the study of Chinese civilization.” Implicit here perhaps is the recognition that Christianity is the creator of, but is bigger than, Western culture, and it is only those who have lost that culture (that is, secularists) who have the bigger problem with cultural difference.

Early in the book, Paquet discusses Leys’ faith. In particular he notes the importance of the Mass to Leys, the centrality of prayer, and the example of a teacher whom he called “a man of luminous holiness”: “[t]he most convincing thing in faith is when you’ve seen it put into practice and it works.” Paquet recognizes that his contemporaries saw in Leys a moralist in the vein of Simone Weil and Georges Bernanos. Leys famously defended Mother Teresa against Christopher Hitchens in the pages of the liberal New York Review of Books. Paquet discusses the controversy, as well as some of the other public positions Leys took on issues of religion and traditional morality, yet subtly underplays their importance. Sinology and China were his main preoccupations, it is true, but Leys described himself as “a traditional Catholic…from the start.”

A discussion of how Leys’ faith enriched his scholarship or his writing throughout his later life would have strengthened the biography. At several points, especially in his later period, Leys addressed the emerging progressive orthodoxy around issues such as euthanasia and marriage. On the former, for example, Leys sparred with none other than the governor-general of Australia, who in 1995 wrote a defense of euthanasia. Leys argues that one should defend “the natural greatness” of every person, in the same way one defends “the institutional greatness” of the past actions of a governor-general now gone senile. Otherwise, such a society will have “forsaken the very principle of civilization and crossed the threshold of barbarity.”

Leys’ Catholic faith represents a kind of worldly, non-ideological Catholicism that was once more common in Europe, but less so in the United States. This kind of Catholicism is perfectly comfortable in defending Chinese tradition and spending time translating classics of Chinese philosophy, but is still able to quote Chesterton in defense of marriage and “common sense.” And even as Leys attacked what he saw (quoting Chesterton) as “the inner anarchy that denies all the moral distinctions,” he recognized that because of sin, “innocence escapes us; one way or the other, we are all cripples.” There are too few such Catholics writing for the New York Review of Books these days, and that is a real cultural loss. In The Hall of Uselessness (the title derives from the name Leys and friends used to describe their common hovel where they studied as young men in Hong Kong), there is his admiration for Chesterton and Waugh, for example, both as writers and as prescient observers of our cultural scene. Leys notes that the secularism of Waugh’s world is very similar to that of our own—a culture that desires the benefits of religious belief and practice while dispensing with belief itself.

Leys notes that “the meanest judges in this world were not even able to keep [Waugh] for one single day in their literary purgatory; as to the other one, God’s sweet mercy will have taken good care of that.” Such a sentiment applies equally well to Leys himself.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Such remarkable people, these Catholic men of letters, who lived across time: born when one could access real living traditions – before the ravenous demolitions of leftists east and west put these traditions to the fire and the sword.

The chasm they looked across…