The Educational Guidance Institute (EGI), founded and directed by Dr. Onalee McGraw, uses classic film to teach universal truths to today’s youth. EGI’s study guides have been used in public, charter, Catholic, and religious school classrooms; after-school programs; special events in detention homes and alternative schools; pilot programs for college students and young adult groups; homeschools and homeschool co-ops; and parent-teen events in communities and churches.

The Educational Guidance Institute (EGI), founded and directed by Dr. Onalee McGraw, uses classic film to teach universal truths to today’s youth. EGI’s study guides have been used in public, charter, Catholic, and religious school classrooms; after-school programs; special events in detention homes and alternative schools; pilot programs for college students and young adult groups; homeschools and homeschool co-ops; and parent-teen events in communities and churches.

CWR spoke with McGraw about the EGI’s classic movie study guide program, and why classic movies are ideal vehicles for teaching students about truth, goodness and beauty.

CWR: We are all conscious of the loss of the transcendent in our world today. What is it that makes classic film effective as a tool for educating and evangelizing the rising generation?

Dr. Onalee McGraw: What makes studying classic films in group settings so effective is the timeless power of the story to move the heart through the imagination. The depth of the emotional response can vary based upon each person’s personality and life experience, but most viewers cannot help coming away with a better understanding of who they are and their place in the mysterious universe we share. The tragic loss of community, solidarity, and identity can be confronted with films that invite the viewer on a journey of the moral imagination. For example, our study guide for It’s a Wonderful Life provides a comparison of Bedford Falls and Pottersville. The students discuss the elements of community that they see present in Bedford Falls and absent in Pottersville. With seven films in [the study guide] “The Feminine Soul,” mothers and daughters can gather together to explore the timeless features of womanhood. We see female characters as whole persons, such as Olivia de Havilland recovering from mental illness in The Snake Pit and Grace Kelly making choices about the men in her life in The Country Girl. With our study guide “Men of the West,” the masculine genius is on full display in movies such as Shane and The Magnificent Seven. The beauty of authentic love can be explored in “Men and Women in Love: The View from Classic Hollywood.” Watching and discussing these classic films, the viewers—regardless of experience and cultural background—will encounter intangible meaning and truth in the concrete images and dialogue they see and hear.

CWR: The films featured in your study guides were created when the Motion Picture Production Code was in use. Tell us why the Production Code came about, what it was, and why you believe it was a force for good.

McGraw: The Motion Picture Production Code was accepted by the Hollywood studios in 1930. It was developed by Father Daniel Lord with a strong philosophical tone and approach. The movies had turned to sound, and the whole question of vivid presentation—not only of images, but of dialogue—was a growing concern. The moral nature of the times was such that state and local censorship boards across the country with a broad range of opinions would object and even ban films the studios had already spent money to produce. This state of affairs continued after 1930 when the Code had been adopted. The studio people knew that something was needed to enforce the Code or federal censorship was almost certain.

To implement the Code, the Production Code Office was established in 1934, and its effects were immediate. The first principle of the Code was, “No picture shall be produced that will lower the moral standards of those who see it.” Another principle was, “Law, natural or human, shall not be ridiculed, nor shall sympathy be created for its violation.” But how do you translate the “natural law” of the Code into practical suggestions for a screenplay? The Production Code Office was headed by Joseph Breen, a Catholic layman who understood and believed in the natural law principles upon which Father Lord had built the Code. The Code Office provided moral consistency for the public and clarity and guidance for the studios for over two decades. Film historian Thomas Dougherty draws a conclusion undisputed by other film historians: “The era of Hollywood’s Golden Age began with the Code and ended with its demise.”

CWR: With all the issues of the day that have so deeply divided us, what are some examples of classic films in your project that serve to unite us?

McGraw: Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, No Way Out, and 12 Angry Men are films that can go a long way towards overcoming the group identity politics poisoning our civil discourse. Consider Mr. Smith. The characters played by Jimmy Stewart and Jean Arthur model the civic virtues that sustain a free society; Jeff Smith gains the courage to fight from Saunders in the famous scene at the Lincoln Memorial. In No Way Out, Sidney Poitier’s very first film, the abstract principle of universal human dignity is made concrete in a counterintuitive way. Poitier’s character, Dr. Luther Brooks, is a black man persecuted by a psychopathic racist (reluctantly portrayed by Richard Widmark). Dr. Brooks is called to honor the racist man’s human dignity by tending to his medical needs. As he explains in the final scene, “I can’t kill a man just because he hates me.” 12 Angry Men dramatizes the necessary link between truth and justice, conveyed in almost every scene. Henry Fonda’s juror Number 8 helps the other jurors imagine and reason their way to a united decision. All of the films EGI includes in the study guides inspire young people to recover a sense of our common humanity

CWR: Why use classic films over, say, a classic literature course for young people?

McGraw: With literature, the reader still has to create the images through the imagination, and many young people are not capable of that today. Many forces are at work against the formation of a healthy imagination. Great literature is increasingly vilified or dismissed in public schools, but great classic films, by their elevated place in our American culture, still claim broad allegiance and provide universal significance and immediate appeal. This makes them highly accessible in even hostile and toxic public school environments.

In terms of evangelization of the “nones,” I cannot imagine a better opportunity to provide a vision of beauty, goodness, and truth to a generation starved for meaning and belonging. The study guides focus on elements of classical education such as vocabulary development, critical thinking, and putting each film in its historic and cultural context.

CWR: The wave of sexual harassment and sexual assault allegations in the media, Hollywood, and academia has roiled the country for months now. Is there anything classic movies can teach young people about this phenomenon, and how men and women should relate to one another?

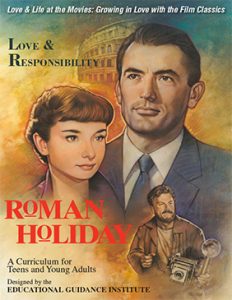

McGraw: Classic movies feature characters as whole persons interacting with each other in relatable (and sometimes not so relatable!) life situations. One of the appealing features of classic film is that the personal, communal, and cultural spheres of life are integrated and seen as an organic unity. The men and women in these stories must confront moral choices in a real-world context. In our postmodern world, there are desperate attempts on college campuses to reconstruct practical norms for male-female interaction with methods such as “consent contracts.” In films like Roman Holiday, It Happened One Night, and Johnny Belinda, the bonds and connections between people are so realistic and compelling, the viewers can readily identify with and internalize them. Through their imaginations, they can apply what they see on the screen to their own lives. This cohesive view of reality seen in classic film is more believable and compelling than any attempts to further compartmentalize human interaction.

CWR: Do you have any incidents in the program’s history that gave you an indication of the power of classic films to inspire the imagination?

McGraw: When we showed It’s a Wonderful Life to a group of fatherless young men in a detention home, at first they hated the movie because it was in black and white. Plus, they didn’t know who Jimmy Stewart was, and they were deeply depressed. The teacher begged them to give the film a chance and they agreed. At the point in the film when Jimmy Stewart jumps into the water to save Clarence, these young men were drawn into the story so deeply that when the film concluded they said that it was the best movie they had ever seen. C.S. Lewis would have understood this as the power of the imagination at work. As Lewis said, the imagination is “the organ of meaning.” What these young men intuitively knew from seeing all the events in the film unfold is what we all know from every scene in the film: the life of every person is valuable.

I witnessed another powerful example of how the imagination works at an early pilot we did with the Humphrey Bogart/Lauren Bacall classic Key Largo. One of the teens in the group seemed completely distracted and he had spent most of the time ripping up red plastic cups to cure his boredom. We stopped the film for discussion at the very point when the hurricane starts to blow and Bogart challenges gangster Edward G. Robinson, who is obviously very threatened by the hurricane. Our youth leader turned to the cup-ripping character and asked him directly, “What is a coward?” Amazingly, without much hesitation, the young man answered, “A coward is someone who is afraid because they can’t control events.” This surprisingly high-level response can only be explained by the power of the great actor Edward G. Robinson to convey the sudden fear he experienced after bullying and killing people from the beginning of the movie. The images and dialogue passed from this young man’s distracted senses into his imagination, and developed into an objective understanding of the vice of cowardice.

CWR: If an educator reading this wants to order one of the study guides, what does he or she need to do?

McGraw: The study guides can be ordered on Amazon.

Individual movies for each study must be purchased or rented separately.

For more information on the EGI, visit www.educationalguidanceinstitute.com.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply