They can imprison me, arrest me, and cause a scandal, but I cannot stop my activity, which is a service rendered to the Church, the fatherland, and my people. – Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko

Even some Catholic thinkers are prone to misconstrue the Cold War as a tidy vindication of liberal democracy over Communism, which is a reading that makes little more sense than attributing the defeat of the Third Reich to Stalinism. There were many cultural, spiritual and moral forces in play during the Cold War, and such forces often had next to nothing to do with Keynesian economics, Rawlsian jurisprudence, or the longstanding Lockean campaign against patriarchy. Even if we confine ourselves to the American sphere alone, many (if not most) of the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and statesmen who contained Soviet power did so not to champion “democracy” in the abstract, but to defend national sovereignty and religion from a godless international revolution. So to conceive the Western counter-communist campaign solely in terms of the liberal narrative is to appropriate the work and sacrifices of men who in many instances gave their very lives.

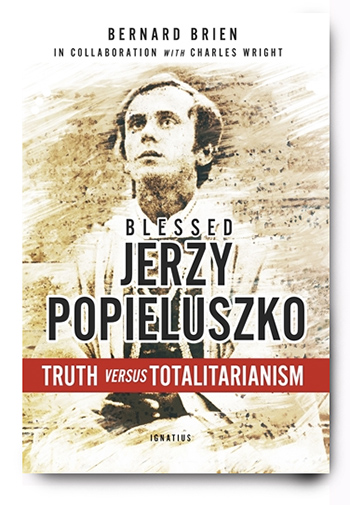

Some of the most egregious examples of such appropriation are to be found with respect to Polish history, which has for years now been mistaken by establishment conservatives as merely a convenient vehicle for the American elite’s liberation ideology. Which is one reason why Bernard Brien’s Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko: Truth versus Totalitarianism could not have come at a better time. Written by a parish priest who witnessed a miraculous recovery attributed to Popieluszko, this slender volume reminds us that the age of saints and martyrs is not quite past. It also makes clear to the attentive reader the true motivation behind Polish resistance to Communist occupation: God and country.

Born in 1947, Popieluszko grew up on a farm in a hamlet named Okory, where he learned from his parents and siblings “the homespun values that unfolded throughout his life: humility, dedication, industriousness, a sense of the effort, dignity, and love of his ancestors, whose memory must be honored, since one owes to them what one is.” Popieluszko’s catechist would later describe the boy as “religiously insatiable” and passionately committed to “all the degrees of holiness”—and so it came as no surprise to anyone when the seventeen-year-old Popieluszko left home for the seminary at Warsaw. His ordination was delayed by a mandatory two-year stint in the army, but the time was hardly wasted: Popieluszko’s military superiors unwittingly trained him not for soldiering but for martyrdom through their attempted bullying and the occasional beatings they meted out as punishment for his refusal to renounce his vocation.

After completing his military service Popieluszko returned to Warsaw and in 1972 was ordained at the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist. He also renewed his acquaintance with anti-communist resistance leader Stefan Cardinal Wyszinski, a towering figure of modern Polish history who was himself recently declared blessed. Although Wyszinski served as Popieluszko’s de facto mentor and was enormously admired by the younger man, the difference between the two personalities could not have been more stark. The cardinal was a very measured, prudent diplomat whose temperate demeanor concealed a resolution undaunted by his previous apprehension, interrogation, and three year house arrest by Communist authorities. Wyszinski’s protege, by contrast, was a crusader “whose only ammunition was his courage and the Holy Spirit.” Where Wyszinski patiently but persistently sought to outmaneuver the Marxist-Leninist regime, Popieluszko openly defied it at the height of his career as a dissident.

That career began with the rise of the Solidarnosc (or Solidarity), a labor union, of all things, in a country that had supposedly anointed the workers as rulers. Under the leadership of an electrician named Lech Walesa, laborers dissatisfied with heavy-handed socialist mismanagement launched a nationwide strike in 1980, and when the group requested that Cardinal Wyszinski provide them a chaplain all the prospective candidates bowed out – with the exception of the idealistic young priest from Okory.

“I will never forget that day,” Popieluszko wrote of the first Mass he celebrated at a Warsaw factory as the Solidarnosc chaplain, “I was terribly nervous; I had never been in a situation like that.”

At the doors of the steelworks, I had my first major shock. A dense crowd was waiting for me, smiling and in tears at the same time. They applauded me, and I thought for a moment that a celebrity was walking behind me. But no, the applause was actually meant for me, the first priest who had ever walked through the entrance of the steelworks. I told myself then that they were giving an ovation to the Church that for thirty years had been knocking on the doors of the factories. All my apprehension proved to be groundless: The altar had been prepared in the middle of the square as well as a cross that then was erected at the entrance […] The lectors were there, too. You had to listen to them, those hoarse voices accustomed to swear words, solemnly reading the sacred texts. Then from thousands of mouths came a cry like thunder: “Thanks be to God.”

With this, Popieluszko more or less became one of the standard-bearers of Christian Poland, and for the rest of his life he exhorted Polish youth to emulate the eagles portrayed on Poland’s national flag: “You must fortify your soul and raise it very high so as to be able to fly above everything, like them. Only by resembling eagles will you brave the winds, the storms, and the tempests of history, without allowing yourselves to be enslaved to falsehood.”

To this day countless Poles vividly remember the homilies given by Popieluszko during his famous “Masses for the Fatherland”. The rest of us would do well to familiarize ourselves with them as well, for they contain messages that are at least as relevant to 21st-century Western Europe and America as they were to 20th-century Poland:

Although it is true that Jesus Christ was sent to the whole world, to bring the Good News to all peoples and nations, it must be recognised that he also had his own country here on earth. A particular country, with its own history, religion and culture. He freely accepted some of the laws of his country, in spite of the fact that no man-made law could be binding upon God made man.

By this he wanted to underline how important it is for us to realise that we all have a country of our own. All human beings are intimately connected with their respective countries, through their families and their place of birth. Our country, our Fatherland, our own native culture, every event in its history, be it a source of joy or grief, is our common heritage. The riches of our language, our works of art and music, our religion and our customs, are all a part of it.

In light of this it is worth quoting Brien, who notes that in response to Popieluszko’s homilies “the State propaganda machine launched press campaigns to portray him as an activist propagating hatred.” As Popieluszko observed, the real hatred is found among those seeking to disinherit the next generation:

One cannot expect that a nation can abandon its past and start again from scratch. And we must not remain silent when our culture, our art and literature, is treated with contempt by those responsible for the education of our children; when Christian morality is replaced by a dubious socialist morality; when teachers in Warsaw schools openly declare to Christian parents that their children’s education will be secularised.

To ban Christian truths, which for centuries have formed an intimate part of our national life, from the presence of children is to begin the destruction of their national identity. The school must teach our young people to love their country, to be proud of their national heritage.

Here there is nothing to add. Either the reader recognizes Popieluszko’s point about the indispensability of roots – of native culture, art, literature, and heritage – or he doesn’t.

During his tour as Solidarnosc chaplain, Popieluszko received death threats, had his windows blown out by a bomb, and was subjected to a coordinated campaign of police intimidation that included bugging his phone and planting evidence in his apartment. No man of steel, Father Popieluszko suffered from gnawing fears. But, as Brien relates, the young priest made a conscious decision to keep his fears from getting the better of him. Whenever Popieluszko found himself smothered by anxieties, he prayed all the more intensely, and renewed his strength via fellowship with Solidarnosc and his brother priests. It became clear to the Communists that mere threats had accomplished nothing, and would only provoke their target to push himself even further in his service. If the common Polish workers drew great inspiration from him, many Communist officials came to regard him with an obsessive hatred.

On the night of October 19, 1984, Popieluszko got into a car bound for Warsaw following a rosary in the town of Bydgoszcz; his friends would never see him again. His frantic driver turned up the next day, reporting that the car had been pulled over by a group of men who had apprehended the priest after having identified themselves as police officers. At first no one knew who the men were, or where they had taken Popieluszko, and as the news of his abduction broke the nation was stunned with grief. Even the Communist leadership itself grew alarmed, as the actions of what appear to have been overzealous, renegade security personnel pushed Poland in the direction of insurrection, which in turn might easily have prompted a heavy-handed Soviet intervention.

Popieluszko’s influence remained, however. “Let us pray that we may be freed from fear and intimidation,” he had said in his very last public exhortation, “but above all from the desire for revenge and violence.” Thus was his country spared disaster, shocked and furious though his Solidarnosc brethren became when Popieluszko’s body was discovered in an artificial lake several hundred miles outside Warsaw, bearing the telltale signs of mutilation and murder. The righteous anger was there, but thanks to Popieluszko’s preaching this energy was channeled into avenues more productive than revolution.

Instead of the shattering of glass or rumble of Soviet tanks, his life was punctuated by a much more fitting sound, that of the liturgy:

The solemn funeral Mass began, with the primate of Poland presiding. Outside there was a sea of human beings. More than a half million Poles came to pay their homage to the martyr of their nation. Aside from the papal journeys, the country had never experienced such gatherings! All around the church, this impressively dignified crowd waved candles, flowers, crucifixes, and Solidarnosc banners. On some banners an inscription read: “Saint George, you will help us to defeat the red dragon,” an allusion to the legend of the victorious battles of George – in Polish, Jerzy – against the monster, which is compared here to the Communist dictatorship.

Poland’s Communist dictatorship did indeed fall, thanks in part to Father Popieluszko’s sacrifice, as well as to the leadership of Cardinal Wyszinski and John Paul II. Yet the struggle between truth and totalitarianism is far from over, and if Catholics in the U.S. are serious about fighting the good fight we might remind ourselves that Poland was a Christian nation long before Leif Erikson got his sea-legs, to say nothing of Columbus, John Smith, or the Pilgrims. The Polish experience spans ancient paganism, the Reformation, partitioning by Europe’s great powers, and the agony of successive Nazi and Communist occupations.

A case can surely be made that with respect to the Poles, Americans could do less lecturing and more learning. Not all dragons are red, after all, and in any event it is not in Warsaw but the pages of the New York Times where we now find ostentatious praise of the sage Karl Marx. Communism’s many ideological cousins remain, firmly ensconced in teachers’ unions, universities, think-tanks, and corporate offices throughout the West. Even if he has won his crown, the work of “Saint George” has only just begun.

Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko: Truth versus Totalitarianism

by Bernard Brien

Ignatius Press, 2018

Paperback, 125 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

I would like to think of Jerzy Popieluszko as a saint. We do need more saints, especially in a time like this when their opposites are so obvious in the RC Church. But the seeming need for a big spiel like this to prove it (respectfully) makes me wonder. Either way though, “requiescat in pace”

I would like to think of Jerrzy Popieluszko as a saint. In this time where many of their opposites hold forth in the RC Church, there is a special need for saints. But the seeming need for a big spiel like this to prove it, very respectfully makes me wonder. Anyway may he rest in peace.

“Big Spiel” (previous comment): I do not have the time to read all the stimulating weekly articles from CWR. It would be really good if they could be prefaced by a brief summary, say, 3 or 4 paragraphs followed by the full text.

The age of “matyrs (sic) is not quite past.” Not QUITE past? Not past at all. Witness what is happening in the Middle East, China and a host of other countries including some in Europe (see the regular reporting of Hate Crimes Against Christians from the Observatory on Intolerance & Discrimination [observatory@intoleranceagainstchristians.eu].

‘The age of Saints and Martyrs’ will NEVER be past – have we not even learned that much?.