“But ‘tis the talent of our English nation/still to be plotting some new Reformation” – John Dryden

Introduction: Catholic endurance during the English Reformation

Oxford, which I visited for two weeks this past July and August, is perhaps the most beautiful city I have ever visited. Another American, Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864), once wrote of it: “The world surely has not another place like Oxford; it is a despair to see such a place and ever to leave it, for it would take a lifetime and more than one to comprehend and enjoy it satisfactorily.”i But Oxford has not always been the Elysian Fields for those who are Catholic, who are members of the faith that Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman (1801-1890) referred to as “one true fold” of Christ.

During the summer months, large crowds of tourists – many of whom are Chinese, some wearing Hogwarts scarves and brandishing wooden wands – assemble on the steps of the towering Gothic Martyrs Memorial positioned at the intersection of St Giles’, Magdalen, and Beaumont Streets, near Balliol College. Three celebrated Protestant martyrs are commemorated on this imposing monument: Hugh Latimer (1487-1555), Nicholas Ridley (1500-1555), and Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556). Each of these men was burned at the stake on Broad Street in Oxford during the reign of Queen Mary I (1516-1558), the Catholic monarch who sought to reverse the English Reformation after the notorious rule of her father, King Henry VIII (1491-1547). Little more can be said of this era than that brutality and intolerance reigned on both the Roman Catholic and Protestant sides of the conflict.

The most celebrated of these three Protestant martyrs is Thomas Cranmer, the author of the Book of Common Prayer, still in use among followers of the Anglican Communion. Cranmer’s death is forcefully recounted in John Foxe’s (1516-1587) stridently anti-Catholic work, Foxe’s Book of English Martyrs. After asserting, “And as for the pope, I refuse him, as Christ’s enemy, and antichrist, with all his false doctrine,”ii Cranmer advanced into the flames, and “when his body began to burn, he stood so steadfast that he moved no more than did the stake to which he was bound,” and uttered his last words, “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.”iii As stirring as this account is, the great majority of Oxford’s Christian martyrs were Roman Catholic, whose stories have been largely suppressed by England’s Protestant authorities. In his book, John Foxe claims that as soon as the Catholic Queen Mary I had died, “The furious firebrands of cruel persecution, which had consumed so many poor bodies, were now extinct and quenched.”iv This was true only for Protestants. What very few tourists in Oxford (or residents for that matter) know, is that only a short walk from the Protestant Martyrs Memorial is the so-called “Catholic Martyrs Memorial,” at the end of Holywell Street, dedicated to four Roman Catholics who were executed in 1589 for refusing to deny the pope and accept the new religion of the empire.

The small black plaque commemorating these Catholic martyrs is hardly visible as one passes by; it is suspended above a window in such a fashion that it is nearly unnoticeable unless it is pointed out. As the authors of a Catholic News Service article note: “When officials at the university’s Merton College agreed in October 2008 to allow the house to be used to commemorate four Catholics executed under Queen Elizabeth I, the move was resisted by some city council members. After more than four centuries, the story of Oxford’s [Catholic] martyrs still provokes unease.”v The circumstances of Catholic martyrdom under Protestant England were at least as gruesome as those who died under Queen Mary I (1533-1603), and they were far more frequent. Two of the Catholic martyrs, Father Richard Yaxley (d. 1589) and Father George Nichols (1550-1589), were arrested at midnight in May of 1589 after secretly offering Holy Mass at Oxford’s Catherine Wheel Inn, during a wave of repression against the outlawed “Old Religion.” After being tortured in London, they were brought back to Oxford to be hanged, drawn, and quartered.vi

According to the Oxford Oratorian, Father Jerome Bertram, CO, by the time Queen Elizabeth I (who Catholics call “Bloody Bess”) had died, fifty former members of the University of Oxford and four locals had suffered martyrdom under Protestant Reformers.vii A small pamphlet available in the chapel of the Blackfriars in Oxford tells the stories of the seventy beatified and canonized martyrs associated with Oxford, stories mostly unknown to those who are unaware that more Catholics than Protestants were killed in England during the Protestant-Catholic disagreements.

One of the Oxford martyrs, Humphrey Pritchard (d. 1589), was accused of being a traitor because of his Catholic faith and was forced to endure fifteen hours of torture before being taken to the gallows, where he “silently made the sign of the cross, mounted the ladder, raising the rope to his lips at each step and blessing it,” before he was hanged.viii When another Catholic martyr of the English Reformation was mercilessly killed in 1604 for his refusal to renounce “the old religion,” he reportedly reminded a nearby Anglican minister that while his Catholic faith was indeed “ancient, . . . the new religion crept into the country in the time of Henry VIII.”ix Even though the one-sided version of the English Reformation propagated by the Church of England still prevails in Oxford, the history of violent anti-Catholicism there is finally reaching the ears of interested students of history. Nuanced accounts that illustrate both sides of the story are at last made available.

A series of papers were written and published at the University of Cambridge in 1928 after considerable research on the fate of Catholics during the English Reformation.x Their conclusion was that the conflicts between Catholics and Protestants at that time were caused more by political disagreements than religious ones, a conclusion one rarely hears when listening to tour guides at Oxford discussing the Martyrs Memorials on Broad Street and St. Giles. One of the authors, Joseph Clayton, concludes his study of lay Catholic martyrs with the assertion that for England’s Catholics “the battle for freedom to practice our religion is never done, nor the field ever quiet.”xi Oxford’s Catholics, and indeed all of England’s Catholics, remain a small and harassed minority in a country that has defined its religious identity as merged with, and ruled by, the monarchy.

That said, if one continues walking past the Martyrs Monument onto Woodstock Road, he will soon pass by the magnificent Oratory Church dedicated to St. Aloysius Gonzaga and see a yellow and white papal flag waving above its main entrance. Catholicism is a palpable and flourishing presence in Oxford, and while multitudes of passionate Harry Potter-clad tourists ambulate through the University precincts, they are joined each year on the Feast of Corpus Christi by more than 500 Catholics, accompanied by Oratorians in their distinctive cassocks, and Dominican and Franciscan friars in their medieval habits, processing through the streets with banners and the Blessed Sacrament.

When I asked Father Robert Gay, OP, prior of the Blackfriar community, “What is the present reality for Catholicism here in Oxford?” he quickly responded, “Oxford is now almost like a much beloved Disneyland for Catholics! There are perhaps more priests within this square mile than the rest of England.” To gain a better sense of what Father Robert meant, I interviewed priests in the two most influential centers of Catholicism in Oxford, the Oratorians and the Blackfriars, and then paid an additional visit to the parish priest of the Birmingham Oratory, where Cardinal Newman had lived and wrote his famous defenses of Catholic Christianity.

The Oxford Oratory: An apostolate of Catholic beauty

One can hardly consider the Catholic work of the Oratorians without first mentioning their spiritual debt to their founder, St. Philip Neri (1515-1595). All of the Oratorians I encountered in England are among the most genteel and generous people I have met during my many travels abroad. They take to heart St. Philip’s famous injunction: “In dealing with our neighbor, we must assume as much pleasantness of manner as we can, and by this affability win him to the way of virtue.”xii It was Cardinal Newman who established the first Oratory in Maryvale, England, in 1848, moving soon afterwards to Birmingham, where he converted an old gin distillery into an Oratory.

In the spirit of his congregation, Newman enjoined the English Oratorians to emulate St. Philip, who “welcomed those who consulted him with singular benignity” and who received visitors “with as much affection as if he had been a long time expecting them.”xiii In this tradition, I was thus cordially welcomed to the Oxford Oratory for a private tour of the church and library, followed by a candid interview with one of the parish priests. With five priests living in their community, the Oxford Oratory is able to accommodate a large and active parish, one that faces both the challenges and advantages of serving a very transient community of students, researchers, and tourists who often occupy the Oratory pews for only a few days before returning home. While the priests of the Oratory mourn their inability to become better acquainted with the many persons who pass through their church, they view this transience as “an opportunity to form souls that then go out and witness to others.”

During our conversation in the Oratory parlor, we discussed several topics, including the steady trend toward de-Christianization in the United Kingdom. The Oratory’s approach in Oxford is to avoid acrimonious confrontations with secular society, but rather to follow St. Philip Neri’s advice to turn the world’s eyes toward Christ by being “a counterexample of holiness.” According to Newman, St. Philip compared his method of evangelization to the Jesuits, suggesting that while they “fish with a net” the Oratory “fishes with a single line.” The Oxford Oratory uses particular methods to spread the teachings of Christ, and “catch souls one at a time.” I was told that among the most effective methods of evangelization employed at the Oratory is to make God more visible through Eucharistic processions and adoration. “If you expose people to the Blessed Sacrament, you can then just let God do the work.” In addition to its emphasis on making the Eucharist more visible, the Oratory is committed to the sanctification of souls by making the Sacrament of Confession more visibly available. Hearing Confessions is perhaps one of the central works of the Oratory in Oxford, for as St. Augustine is said to have asserted, “The confession of evil works is the first step toward good works.”

When the Oratorians were asked to take over the pastoral care of St. Aloysius church in 1990, there were only two thirty-minute time slots available for Confession each week, and very few ever showed up. “The Sacrament of Confession,” Father asserted, “must be made visible, no less than the Blessed Sacrament, to work effectively in a parish.” Thus, after their arrival in Oxford the Oratorians have made certain that a priest is available in his confessional before every Holy Mass offered at the church.

Responding to my question about how he perceives the sexual abuse cases now plaguing the Church, Father noted that, “The present crisis in the Church is a crisis of holiness; we would not be in the situation we are now in if everyone, including priests, spent more time in the confessional.” And in addition, anyone who visits the Oxford Oratory will notice that more than adoration, processions, and Confession attracts people to its pews; the beauty of its liturgies are renowned throughout the world.

The Oratory offers three Holy Masses on Monday through Friday, two on Saturday, four on Sunday, and five on Holy Days. There are Masses in the Extraordinary Form (Traditional Latin Mass), and New Rite Masses in both Latin and English that are celebrated with refinement and reverence that is rarely seen elsewhere. In addition to beautiful Masses, the Oratory has scheduled weekly Vespers, Benediction, Exposition, Holy Hours, Rosaries, and a blessing with St. Philip’s relic.

I could not resist asking if the Oxford Oratory ever receives criticism from other Catholic clergy who find such traditional practices “medieval,” or “outdated.” “No,” he responded, “we here in England are perhaps less polarized about liturgy than in America.” And he added, “We never want to be polemical about liturgy; the Oratorians try to avoid controversy, which was Newman’s idea.” The Oratory’s strategy is quite simple, Father insisted, “We follow St. Philip’s belief that using everything that is beautiful is a way of leading people to God,” and it is no secret that Catholics are attracted to beautiful churches and beautiful liturgies.

In the end, I wondered out loud, “What, then, is the particular charism of the Oxford Oratory that has rendered it so popular?” Father paused for several seconds, and said, “We are simply secular priests living in community; we seek to be good and holy men who encourage others to be good and holy through prayer, reading, and the Sacraments.” “Surely,” I replied, “the intellectual climate here at Oxford can be anti-Christian, and you must have a more deliberate strategy than merely holiness and beautiful liturgy to counter the university’s secularism. . . .?”

“No,” he noted, “we leave the intellectual work to the Blackfriars; but still, to be a Catholic today in this context requires courage. You must be courageous,” and the graces of good Catholic teaching and liturgy strengthen us in our encounters with the world. As I departed from my interview in the parlor, which included a confessional, I could not resist meditating on how agreeable the priests are who serve there at the Oratory church, and how they maintain their joyfulness within a historical context rife with anti-Catholicism and persecution. Perhaps it is because they are so attentive to the words of their founder, St. Philip Neri, who taught that, “A joyful heart is more easily made perfect than a downcast one.”

The Oxford Blackfriars: An apostolate of Catholic truth

After departing from the Oxford Oratory, I made the short walk to the Blackfriars, or Dominicans, who were first sent to England by St. Dominic (1170-1221) himself in 1221. Already by Dominic’s death, it was expected that Dominicans should learn well in order to minister to the learned. In addition to their call to preach, priors were summoned to identify friars “suitable for teaching,” and “send them to a center of studies.”xiv As Father Bede Jarrett, OP, (1881-1934) wrote of the Dominican choice of Oxford to establish their first priory in England: “It was the intellectual capital of England” that attracted them most, so they “made their first settlement, not near the Primate nor the King but at the University.”xv Thirteen Blackfriars, so called in England due to the black cappa Dominicans wear over the white part of their habit, first convened at Oxford in 1221, then one of the world’s centers of Roman Catholic study and prayer.

They prospered there until Thomas Cranmer dispatched one of his lackeys, Dr. John London (1486-1543), to force the Blackfriars to surrender their property on August 31, 1538; they were not allowed to return again to Oxford until Catholicism was more tolerated in 1921.xvi Thus they were exiled from Oxford for 383 years. The foundation stone of the present priory in Oxford was laid on August 15, 1921, the 700th anniversary of the founding of the original community, and today the Blackfriars host a Studium for theological studies, a Permanent Private Hall affiliated with the University of Oxford, and the Dominican Priory of the Holy Spirit. The current prior of the community, Father Robert Gay, OP, generously showed me around the Blackfriars buildings and agreed to discuss the situation of their work at Oxford.

Father Robert noted that twelve priests now reside in the Oxford priory, along with nine students who are in formation, and with its three separate divisions the Blackfriars are quite active. Besides the intellectual and sacramental work of the friars, they are acutely aware of what Father Robert calls “the militant secularism” that now pervades in what was in the past a mostly Christian, albeit Protestant, society. While ignorance of Christianity is not uncommon in much of the UK, Oxford retains a profoundly visible Christian presence, and “in terms of feel, Oxford appears very Catholic with all its priests.” In addition to the Oratorians and Blackfriars, Oxford is home to secular priests and other Roman Catholic orders, such as the Benedictines at St. Benet’s Hall, the Greyfriars, or Franciscans, and the Jesuits at Campion Hall. I know of no non-Catholic college or university in the US with such a profusion of Catholic chapels, academic halls, and religious communities. I am inclined to say, however, that the Blackfriars are the most active Catholic intellectual presence at Oxford, whose motto is veritas, or “Truth.” Father Robert assured me that one of the aims of the Dominican friars in his community is to remain an authentic Catholic presence at the university, and to continue serving as a voice of the Church in what he called, “the debates” prevalent in today’s intellectual climate. For a Dominican, the Latin adage, Veritas nihil veretur nisi abscondi (“Truth fears nothing but concealment”) functions as a constant reminder of his or her role at a university.

As a bioethicist, Father Robert is naturally devoted to encouraging the Church’s defense of life, and among the most discouraging dimensions of Oxford’s current culture, he recalls, is the aggressive secularism among some of the student body. Oxford’s Students for Life group, for example, has encountered vitriolic opposition to its organized events. In 2017 during a Students for Life talk, a rival student group called the “Women’s Campaign,” or “WomCam,” disrupted the event by shouting slogans for half an hour.xvii In the end the police were called to control the fifteen angry protesters, and the pro-life event was forced to relocate. While disagreements on important issues such as abortion sometimes manifest in open conflict at Oxford, the Blackfriars seek to provide a venue for civil and rigorous intelligent engagement through both their presence and through redirecting “the debates” toward more foundational approaches to intellectual enquiry. In typical Dominican fashion, the Oxford Blackfriars established the Aquinas Institute in 2004 under the directorship of Father Fergus Kerr, OP, to provide a venue for the thorough examination of philosophical and theological questions. In other words, the Oxford Blackfriars have created a space for academic work that will help infuse graciousness and scholarly precision in the discussions that transpire at the university.

With such a distinguished assembly of friars and a group of around forty students, Father Robert is confident that the Dominican charism of prayer, blessing, and preaching provides a healthy and robust Catholic voice at Oxford, and he defines himself as an enthusiastic “guardian of Dominican identity,” both among the local Catholic community and within the academic society of the university. One of the ways the Blackfriars maintain a visible presence at Oxford is by wearing their distinctive habits; one perceives the continuity with Oxford’s medieval Roman Catholic origins when she or he sees the Blackfriars in their religious habit, “armed,” so to speak, with the rosary hanging at their left hip. I attended Holy Mass on Sunday evening at the Blackfriars chapel, and it was quite edifying to see the deliberate reverence with which they celebrate the sacred liturgy and how well attended was the Mass. After the conclusion of the Mass, the faithful turned toward a graceful carving of the Blessed Virgin Mary positioned near the front of the sanctuary, and collectively intoned the Salve Regina (Hail Holy Queen) in Latin. While chatting with Father Robert, he reminded me that the Blackfriars chapel was among the frequent haunts of the famous Catholic scholar and novelist, J. R. R. Tolkien (1892-1973), who used to occasionally serve at Holy Masses with their priests, and was inspired by artistic depictions on the Stations of the Cross there as he wrote his popular stories.

Before I departed, Father Robert said that, “Universities are our home,” and he is grateful that their spiritual and intellectual work at Oxford is now sought after by interested students and aspirants to the Dominican order. He is hopeful that Oxford will continue to serve as a center for Catholic culture and growth as England continues to face cultural, religious, and financial challenges in the twenty-first century. Returning to my lodging at St. Anne’s College, I reflected on the life and legacy of the most famous Blackfriar to have lived, written, and taught at Oxford, Father Bede Jarrett, who wrote the bidding verse: “May He give us all the courage that we need, to go the way He shepherds us. That when He calls we may go unfrightened.” This, I believe, describes well the spirit of Oxford’s Blackfriars today.

The Birmingham Oratory: Still resound there the echoes of Newman

It may at first seem irrational that to fully apprehend the situation of Catholicism in Oxford one should travel an hour away by train to the industrial city of Birmingham. But there is really no way of understanding Catholicism in the UK today unless one considers the influence of Cardinal Newman, whose conversion from Anglicanism to Catholicism occurred while he was teaching and preaching in Oxford. An Anglican librarian confided in me during lunch at Oxford that Newman’s contribution to the Oxford Movement still haunts Anglicans who, after reading his writings, “must overcome difficult mental hoops to avoid arriving at the same decision that Newman did,” namely, to convert to the Catholic Church.

The Oxford Movement, which was orchestrated by a luminous group intellectuals during the mid-nineteenth century, was largely fueled by the ideas of two Anglicans of genius, John Henry Newman, who became a Roman Catholic, and Edward Bouverie Pusey (1800-1882), who was the principal founder of Anglo-Catholicism. I travelled to Birmingham because that is where Newman spent the final decades of his life, and that is where the Oratorians still represent the mind and soul of the Oxford Movement that Newman inaugurated.

One of the main characteristics of the Oxford Movement was its reaction against Erastianism, or the doctrine that the state should in all matters have control over the Church.xviii Put simply, Cardinal Newman reviewed the Church Fathers and the history of Christianity, and, in essence, read himself into the Catholic Church. Newman’s studies revealed to him that the Church of England is a “National Church,” and as a result it “did not in fact rest on the idea of primitive Catholic Christianity but on that of royal supremacy.”xix The Oratorian church in Birmingham, then, remains a living sign of Blessed Newman’s important role in the revival of Roman Catholicism in the United Kingdom, and what one discovers when visiting there are the manifold echoes of Newman’s abiding example of faithfulness to the rich doctrines and beautiful liturgies of the Catholic faith. In a letter to a friend, Newman wrote that, “We can believe what we choose. We are answerable for what we choose to believe.”xx Helping others find their way to the truths of Catholicism and helping assure the persistent health of souls are the visible aims of Newman’s successors at the majestic Birmingham Oratory.

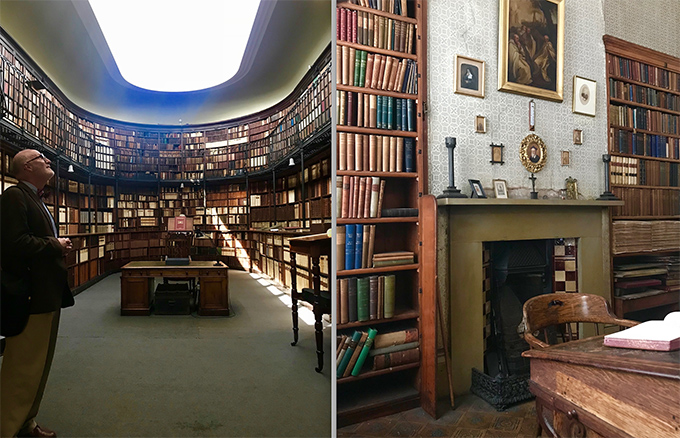

I arrived at the Oratory in the early afternoon and was met by the parish priest while admiring the nave of the grand Baroque-style church dedicated to the Immaculate Conception. After a detailed tour of the church and National Shrine of Cardinal Newman, we passed through the sacristy and upstairs to the library and private rooms of John Henry Newman. The feeling of amazement one has while walking through Newman’s immense library is only surpassed by standing beside the altar of his private chapel, where he offered daily Mass and prayed for his friends, family, and the Church in his native England. Like their confreres at Oxford, the Birmingham Oratorians permeate their liturgical rites with great beauty and reverence. So influential was Blessed Newman’s preference for splendid liturgies, that Henry Edward Cardinal Manning (1808-1892), who served as the archbishop of Westminster during Newman’s life, also preferred the “High Church” aesthetics that attracts so many people to Newman’s Oratory. Newman’s preference for liturgical and architectural beauty can still be detected in England’s Catholic Church. After a long afternoon of visiting the many spaces once occupied by Blessed Newman, I could see how true the assertion is that he was not only responsible for the revival of Catholicism in Oxford, but also of its revival in all of England.

Conclusion: The Catholic future of “Protestant” England

When one of England’s most celebrated poets, John Dryden (1631-1700), became a Roman Catholic, he paid a high price for his conversion. He was stripped of his position as poet laureate and suffered all the penalties imposed upon Catholics by the British government. That was more than three centuries ago. Today, the Bodleian Library has staged one of its most popular exhibits, one with enormous daily lines hoping to gain access to the overcrowded rooms. The exhibit, “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth,” features the original drawings, manuscripts, and personal objects of one of history’s famous and devout Roman Catholics, J. R. R. Tolkien.

Anti-Catholicism has not entirely gone away in England, but the growing presence of practicing Catholics has made it increasingly difficult to suppress them as in the past. While Dryden was punished for his Catholicism during the height of anti-Catholic England, Tolkien’s Catholic faith is clearly acknowledged – almost celebrated – in the Oxford exhibit dedicated to his life and work. University cities are seldom today locations of Christian revival, but the vibrant Catholic presence at Oxford today provides a healthy counterbalance to the secularizing trends that afflict the Academy. While debates persist within Oxford’s intellectual community, such as whether Christianity should continue to be a compulsory topic of study for first year theology students, there are Catholic priests, religious, and students who remain engaged in these debates, and Newman’s legacy of being a Catholic word in a largely non-Catholic world persists in the streets and halls of Oxford.xxi The Oxford Movement was essentially a Catholic movement, and we can still hope that Oxford continues to move, perhaps slowly and with difficulty, back to its Catholic roots.

Endnotes:

i Quoted in the Educational Review, Vol. 31 (January-May 1906), 19.

ii John Foxe, Foxe’s Book of English Martyrs (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1981, originally published in 1563), 303.

iii Foxe, Foxe’s Book of English Martyrs, 305-306.

iv Foxe, Foxe’s Book of English Martyrs, 398.

v Jonathan Luxmoore and Malgorzata Glabisz-Pniewska, “For Oxford’s Catholic Martyrs, Widespread Recognition is Fleeting,” Catholic News Service (24 February 2011).

iv Luxmoore and Glabisz-Pniewska, “For Oxford’s Catholic Martyrs, Widespread Recognition is Fleeting.”

vii Fr. Jerome Bertram, CO, Catholic Pilgrim’s Guide to Oxford (Oxford, UK: Guild of Our Lady of Ransom, 2015), 23.

viii Catholic Martyrs of Oxford, pamphlet published by the Oxford Blackfriars/Dominicans (St. Giles Street, Oxford, Retrieved 2017).

ix Catholic Martyrs of Oxford,

x See The English Martyrs: Papers from the Summer School of Catholic Studies held at Cambridge, July 28-Aug. 6, 1928 (Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons, 1929). Certainly, the most famous scholarly work on the English Reformation that outlines the historical suffering of Roman Catholics is Eamon Duffy’s The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992).

xi Joseph Clayton, “Martyrs of the Laity, A.D. 1535-1680,” in The English Martyrs, 304.

xii Quoted in The Maxims and Sayings of St. Philip Neri (Potosi, WI: St. Athanasius Press, 2009), 9.

xiii Quoted in Meditations and Devotions of Cardinal Newman (London: Baronius Press, 2010), 104.

xiv M. H. Vicaire, OP, Saint Dominic and His Times, translated by Kathleen Pond (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), 358.

xv Quoted in Aidan Nichols, OP, Dominican Gallery: Portrait of a Culture (Herefordshire, UK: Gracewing, 1997), 408.

xvi Dominicans in Oxford, pamphlet published by the Oxford Blackfriars/Dominicans (St. Giles Street, Oxford, Retrieved 2017).

xvii Dan Hitchens, “Oxford student officials disrupt pro-life event,” Catholic Herald, 2 November 2017.

xviii Harold L. Weatherby, Cardinal Newman in His Age: His Place in the English Theology and Literature (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1973), 235.

xix Weatherby, Cardinal Newman and His Age, 237.

xx John Henry Newman to Mrs. William Froude, 27 June 1848. Quoted in Edward Short, Newman and His Contemporaries (New York: T&T Clark, 2011), 135.

xxi See Javier Espinoza, “Oxford Theology Students Can Skip Christianity Lessons,” The Telegraph, 1 April 2016.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

A very interesting piece about an unexpected reality in Oxford. Thanks for writing this!

How long until this is Oxford? The future never arrives for today is here.

https://mobile.twitter.com/DVATW/status/1049257876638916609

An excellent, informative and encouraging article! Thank you.

I enjoyed Professor Clark’s unbridled enthusiasm as much as his depictions of places long familiar to me. The late Stratford Caldecott would have been the preferred tour guide from his vantage point at Plater College in years past. Throw in Caldecott’s fabulous collection of Chestertonia, and the author would have stayed on yet another week! Oxford is a city of old grudges, ancient rumors, and surly ghosts in dark passageways. Those too await your hoped-for next visit, Professor Clark. Meantime, thanks for the tour.

Interesting indeed but sadly, Professor Clark failed to walk south of Carfax. Opposite Cardinal Wolsey’s college, snatched by Henry VIII and re-named Christ Church, he would have found the Oxford University CatholicChaplaincy.

Serving all members of the university but particularly the undergraduates, the Chaplaincy offers a number of daily Masses (at least one a week in a different College), pastoral care by a dedicated team of priests, and popular social events. Those seeking instruction in the faith, counselling or even preparation for marriage, find a friendly welcome

here. The Chaplaincy is, I guess, the parish of the University and it has a distinguished history worth Professor Clark’s notice – next visit perhaps.

Who initiates the “battle” and who goes on the defense? Do we consider other faiths as enemies? Is our religion really setting an example for religious liberty? Can one be too Catholic in our efforts to evangelize? Can our desire to convert render us duplicitous? If religions can’t heal each other what can we expect of our future?

What Catholics need to do, IMHO, is to *stop* fighting for their own, limited, selfish, interests, and, instead of that, they should do the counter-intuitive thing, and defend persecuted atheists, and other despised groups. Atheists really are persecuted, in places like Bangladesh and Egypt. Catholics should defend atheists because that is the right and humane and decent thing to do. Catholics should always defend oppressed non-Catholics of all descriptions, without any silly ideas of gaining by doing so. This would be an infinitely better witness to Christ than the incessant self-righteous inter-religious bickering that far too often all that lurkers see of Catholic behaviour. The CC needs Christians, not apologists.

There is nothing distinctively Christlike in fighting for one’s own limited, selfish interests. All interest-groups do as much. “46If you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Do not even tax collectors do the same? 47And if you greet only your brothers, what are you doing more than others? Do not even Gentiles do the same? 48Be perfect, therefore, as your Heavenly Father is perfect.…” (St Matthew 5).

The setting here could not be more perfect for a Catholic revival, since Oxford literally reeks of tradition in the best way. As it happens, my youngest son and I attended the EF early Mass at the Oratory several years ago, and I was struck by the fact that most attendees, including the priest-celebrant, were closer to my son’s age. Quite an experience, and this article confirms that very good things continue to happen in this once Catholic institution. Great reading.