Note: Marking the death Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI on December 31st, CWR is reposting this interview, first posted on January 13, 2021.

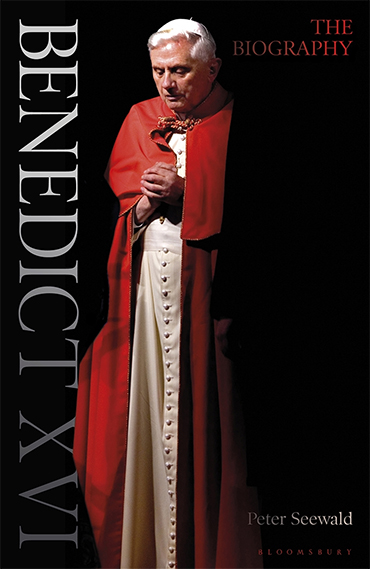

The veteran German journalist Peter Seewald first met Joseph Ratzinger nearly thirty years ago. Since then he has published two best-selling book length interviews with Cardinal Ratzinger—Salt of the Earth: An Exclusive Interview on the State of the Church at the End of the Millennium and God and the World: Believing and Living in Our Time—as well as 2010’s Light of the World: The Pope, The Church and the Signs Of The Times and 2017’s Benedict XVI: Last Testament—In His Own Words.

He is also the author of Benedict XVI : An Intimate Portrait, and the photo-biography titled Pope Benedict XVI: Servant of the Truth.

His most recent book is an ambitious, multi-volumed biography of the pope emeritus. The first volume, titled Benedict XVI: A Life—Volume One: Youth in Nazi Germany to the Second Vatican Council 1927–1965, is available in English.

Seewald recently corresponded with Carl E. Olson, editor of CWR, about his biography of Benedict XVI, and spoke in detail about Ratzinger’s childhood, personality, education, and role in key Church events—especially the Second Vatican Council.

CWR: Let’s begin with some background. When and how did you first become acquainted with Joseph Ratzinger?

Peter Seewald: My first encounter with the then Cardinal was in November 1992. As author of the Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazine I was tasked with writing a portrait of the current Prefect of the Congregation of the Doctrine of Faith (CDF). Even then, Ratzinger was already the most sought after churchman in the world, second only to the Pope. And the most controversial. The reporters stood in line to score an interview with him. I had the good fortune to be received by him. Apparently, my cover letter had sparked his interest, in which I promised to strive for objectivity. And that was indeed what I wanted.

CWR: What sort of access have you had to him over the course of that time?

Seewald: I was not a fan of his, but I asked myself the question: Who is Ratzinger really? He had long since been pigeonholed as the “Panzer Cardinal”, the “Great Inquisitor”, a grim fellow, therefore, an enemy of civilization. As soon as one blew this horn, one could be absolutely certain of the applause of journalist colleagues and the mainstream audience.

CWR: What was different about you?

Seewald: I had studied Ratzinger’s writings in advance and especially his diagnoses of the times. And I was somewhat stunned to see that Ratzinger’s analyses of the development of society had been largely confirmed. In addition, none of the contemporary witnesses I interviewed, fellow students, assistants, companions, who really knew Ratzinger, could confirm the image of the hardliner, on the contrary. With the exception of people like Hans Küng and Eugen Drewermann, his notorious opponents. Of course, I also wanted to see for myself, on site, in the building of the former Holy Inquisition in Rome.

CWR: That was an unforgettable moment?

Seewald: Yes. The door to the visitors’ room, where I was waiting, opened and in stepped a not too tall, very modest and almost delicate-looking figure in a black cassock, who extended his hand to me in a friendly manner. His voice was soft and the handshake was not such that one had broken fingers afterwards. This was supposed to be a Panzer Cardinal? A prince of the Church greedy for power? Ratzinger made it easy for me to strike up a conversation with him. We sat down and started talking. I simply asked him how he was doing. That was the key. Apparently, no one had ever cared about that. As if he had been waiting for this, he completely openly disclosed to me that as of now he felt old and used up. It was time for younger forces and he was looking forward to being able to hand over his office soon. As we know today, nothing came of it.

CWR: How did that access and time together inform this biography?

Seewald: Of course, I would never have dreamed what would follow from that hour. That I would eventually compile four books of interviews with Ratzinger or rather Pope Benedict. I had been expelled from school, didn’t have a high school diploma, had left the Church at the age of 18, and as a juvenile revolutionary I didn’t have much to do with the Faith. However, at some point the cultural and moral decline in our society had made me think. It was clear to me that the disintegration of our standards had to do with the pushing away of the values of Christianity, ultimately with a world without God. I began to look into the questions of religion and found it adventurous to attend church services again. On top of that, I could see that in Ratzinger there was a man who, out of the handed-down Catholic Faith and out of his own reflection and prayer, could provide fitting answers to the problems of our time.

CWR: What qualities did Joseph (Sr.) and Maria Ratzinger possess and instill in their three children – Georg, Maria, and Joseph – so that all the siblings had a strong sense of religious vocation at early ages?

Seewald: Perhaps it must be said that many vocations came forth from the Ratzingers’ ancestral home. One of Joseph senior’s brothers was a priest, one of his sisters a nun, and his uncle Georg, also a priest, had become famous far beyond Germany as a member of the Reichstag and a writer. The family of the future Pope lived a deep piety in the tradition of liberal Bavarian Catholicism. This example had an educational and contagious effect. Benedict XVI said about his mother that she was a very sensual, warm-hearted woman. From her he got the soulfulness, the love of nature. As a policeman, his father was a strict but above all straightforward man who valued truth and justice and, as an anti-fascist, foresaw early on that Hitler meant war.

CWR: How significant was the relationship between Joseph, Sr. and Joseph, Jr.?

Seewald: Extremely important. Through his honesty, his courage and his clear mind the senior was a role model on the one hand, and at the same time Joseph knew that he was truly loved by him. The parents had never insisted that their children should become “something special”. The father was highly intelligent, had a poetic vein, observed the teachings of the Church and at the same time lived a very down-to-earth Catholicism. Above all, he was characterized by a critical mind. He was not afraid to criticize even bishops who had come to terms with the Nazi regime.

Benedict XVI said about his father: “He was a man of intellect. He thought differently than one should think at the time, and with a sovereign superiority that was convincing.” When he was discerning a priestly vocation, he confessed, “the powerful, resolutely religious personality of our father was also a decisive factor for this.”

CWR: What are some key characteristics about Ratzinger’s youth – in terms of both places and events – that shaped his thinking as a teen and young adult?

Seewald: If there is an era in which Ratzinger was perfectly happy, it was the years of his childhood in the baroque Bavarian town of Tittmoning, near Salzburg, shortly before the Nazis came to power. The beauty and atmosphere of this typically Catholic place and the loveliness of the landscape left their mark on him. Ratzinger later spoke of his “dreamland.” It was in Tittmoning that he had “his first personal experience with a place of worship.”

It was not only about the “superficial and naïve pictures”, which naturally can easily impress a child’s mind, but behind them “profound thoughts had already settled early on”. At the same time, he had witnessed how his father, as police commissioner, intervened against Nazi gatherings. He had subscribed to the anti-fascist newspaper “Der gerade Weg” (The Straight Path) and only called Hitler a “stray” and a “criminal”. As a civil servant, he was under pressure to join the Nazi party after 1933 at the latest, which he refused to do.

CWR: You write, “Joseph was also was forced to join the Hitler Youth following his 14th birthday. However, he refused to appear on ‘duty’.” How might you sum up his view of the Hitler Youth in particular and the Nazi movement in general?

Seewald: Joseph experienced how after 1933 priests were persecuted and the Church was increasingly restricted. As a pupil of the Episcopal boarding school in Traunstein, he stayed away from the Hitler Youth until there was a compulsory obligation to join. The fact that he refused to show up for HJ exercises says everything about his courageous attitude towards the hated regime. Even as a schoolboy, he admired the actions of the “White Rose” resistance group. “The great persecuted of the Nazi regime,” he later confessed, “Dietrich Bonhoeffer, for example, are great role models for me.”

Once, in a laudatory speech for his brother, he gave an insight into how drastic the experiences of those years were. The terror of the Nazi regime and the need for a new beginning had strengthened in Georg as well as in him the willingness to dedicate their existence to a life with and for God. “In the headwind of history, in the experience of a non-musical and an anti-Christian ideology, its brutality and its spiritual emptiness,” he wrote, “an inner firmness and determination was formed that gave him strength for the road ahead.”

As Pope, he explained at a 2005 youth meeting at the Vatican that his decision to enter the Church ministry was also explicitly a counter-reaction to the terror of the Nazi dictatorship. In contrast to this culture of inhumanity, he had understood that God and the Faith point the right way. “With her power coming from eternity, the Church”, Ratzinger maintained, had “stood her ground in the inferno that had engulfed the powerful. She had proven herself: The gates of hell will not prevail against her.”

CWR: You mention the impact of reading Guardini, Newman, Bernanos, Pascal, and others, but emphasize in particular how important Augustine’s Confessions were to Ratzinger as a seminarian. Why and how was that book so significant to him?

Seewald: If he could take just two books with him to an island, Ratzinger once told me, they would be the Bible and Augustine’s Confessions. Ratzinger was endlessly inquisitive as a young student. Like a sponge he soaked up the world of the intellect that opened up for him. And while he found the thinking of Thomas Aquinas “too closed in on itself,” “too impersonal,” and ultimately somehow inanimate and without dynamism, in Augustine, on the other hand, he felt, the passionate, suffering, inquisitive person was always directly there, one “with whom one can identify,” as he said. In the Doctor of the Church he discovered a kindred spirit. “I feel him like a friend,” Ratzinger confessed, “a contemporary who speaks to me.” With all the reason, with all the depth of our thinking.

Ratzinger had some patrons, but his real master is Augustine, the greatest father of the Latin Church, as Ratzinger saw him, and “one of the greatest figures in the history of thought.” He found himself so well expressed in Augustine that when he spoke about the Doctor of the Church, it always sounded a bit like a Ratzinger self-portrait: “He always remained a seeker. He was never simply satisfied with life as it is, and as everyone else lives it, too. … He wanted to find the truth. To find out what man is, where the world comes from, where we ourselves come from, where we are going. He wanted to find the right life, not just live along.”

CWR: During his studies, Ratzinger apparently enjoyed lectures given by a wide range of professors, from “progressive” to “traditional”. How did this help him form his theological and pastoral perspectives? And why was Gottfried Söhngen so important to him during that time?

Seewald: After the end of the war, of the Nazi madness, which was also a madness of godlessness, the signs were for departure and renewal. The professors at the Theology Department of the University of Munich were the best in their field. The “Munich School” was characterized by an open-minded and at the same time history-oriented theology.

His doctoral supervisor, Gottfried Söhngen, had immediately recognized Ratzinger’s enormous talent and, with the topic of his doctoral thesis – it was called “People and House of God in Augustine’s Doctrine of the Church” – led him onto a track that, with the teaching about the Church, also had as its goal the love of the Church. Söhngen was someone, Ratzinger said, who “always thought from the sources themselves – beginning with Aristotle and Plato, through Clement of Alexandria and Augustine, to Anselm, Bonaventure and Thomas, to Luther and finally to the Tübingen theologians of the previous century.” The approach of drawing “from the sources” and knowing “really all the great figures of intellectual history from one’s own encounter” had become a decisive factor for him, too.

The topic of his habilitation, which Söhngen had picked for him, is undoubtedly one of the great moments in the life of Benedict XVI. After the dissertation had dealt with the ancient Church and addressed an ecclesiological topic, he was now to turn to the Middle Ages and modern times. The title was “The Theology of History of St. Bonaventure.” Ratzinger’s research results and his formula of the Church as the People of God from the Body of Christ then replaced at the Council the inadequate concept of the Church as the People of God, which could also be understood politically or purely sociologically.

CWR: Why did the young Ratzinger quickly gain so much attention as a priest, professor, and theologian?

Seewald: It was because of the way the world’s youngest theology professor held lectures. The students listened attentively. There was an unprecedented freshness, a new approach to tradition, combined with a reflection and a language which in this form had not been heard before. Ratzinger was seen as the new, hopeful star in the sky of theology. His lectures were taken down and distributed thousands of times throughout Germany.

Yet, his university career almost failed. The reason for this was a critical essay from 1958 entitled “The New Pagans and the Church.” Ratzinger had learned from the Nazi era: the institution alone is of no use if there are not also the people who support it. The task was not to connect with the world, but to revitalize the Faith from within. In his essay, the then 31-year-old noted: “The appearance of the Church of modern times is essentially determined by the fact that in a completely new way she has become and is still becoming more and more the Church of pagans …, of pagans who still call themselves Christians, but who in truth have become pagans.”

CWR: At the time, this was an outrageous, scandalous finding.

Seewald: Certainly, but if you read it today, it shows prophetic features. In it, Ratzinger stated that in the long run the Church would not be spared “having to break down piece by piece the appearance of her congruence with the world and to become again what she is: a community of believers.” In his vision, he spoke of a Church that would once again become small and mystical; that would have to find her way back to her language, her worldview and the depth of her mysteries as a “community of conviction.” Only then could she unfold her full sacramental power: “Only when she begins to present herself again as what she is, will she be able to reach again the ear of the new pagans with her message, who up to now have been under the illusion that they were not pagans at all.”

Here, for the first time, Ratzinger used the term “Entweltlichung” (lit.: de-worldization = detachment from worldliness). With that he followed the admonition of the Apostle Paul that the Christian communities must not adapt themselves too much to the world, otherwise they would no longer be the “salt of the earth” of which Jesus had spoken.

CWR: You write that the “most important Church event of the twentieth century” – that is, the Second Vatican Council – ”seemed tailor-made for him…”

Seewald: One can only understand the Second Vatican Council from its historical context. Pope John XXIII saw the need to seek a new relationship between the Church and modernity in the face of a post-war changed world. In retrospect, it seems like a heavenly coincidence that Ratzinger not only received the chair for dogmatics in Bonn at that time, but after giving a lecture on the upcoming Council he also immediately became a close advisor to Cardinal Josef Frings of Cologne, who was to play a prominent role in Rome. The young theologian was virtually predestined to give decisive impetus to the Second Vatican Council. Without his contribution, the Council would never have existed in the form we know it.

CWR: What are some reasons for that assessment?

Seewald: This already began in the run-up to the Council with the legendary “Genovese Speech”, which he had written for Cardinal Frings. John XXIII said afterwards that this speech expressed exactly what he had wanted to achieve with the Council, but had not been able to formulate in this way. In his opening address, the Pope had then declared, in reference to this speech, that it was “necessary to deepen the immutable and unchangeable doctrine, which must be faithfully observed, and to formulate it in such a way that it corresponds with the requirements of our time.” At the same time, he called it the Council’s task to “transmit the doctrine purely and completely, without attenuations or distortions.”

Ratzinger was well prepared. Some of the task areas that would prove to be the keys of the Council – such as Sacred Scripture, patristics, the concepts of God’s people and of revelation – were his special topics, due to the specifications of his doctoral advisor, Söhngen. And furthermore: Through his education in the “Munich School” he brought with him the vision of a dynamic, sacramental and salvation-historical form of Church, which he set against the strongly institutional and defensive Church image of Roman school theology.

In order to modify the relationship between local and universal Church, between the Office of Peter and the Office of Bishop, he had developed beforehand the image of Communio, which was to become decisive for the Council. The constitution of the Church was to be “collegial” and “federal”; with simultaneous emphasis on the primacy of the Pope and unity in doctrine and leadership.

Moreover, as a connoisseur of Protestant theology and through his preoccupation with world religions, Ratzinger was familiar not only with the issues of ecumenism, but also with the relationship of Catholics towards Judaism. In other words, exactly the subject matter for the schema Gaudium et spes, which, along with the schema on revelation, was to become the most important document of the Council.

Already in his first statements on the schemata prepared by Rome for the coming Council, the then 34-year-old professor guided the 74-year-old Cardinal Frings. Ratzinger’s expert opinions were not only aimed at criticism. In a statement from September 17, 1962, for example, he said: “These two draft texts correspond in the highest degree to the objectives of this Council as declared by the Pope: Renewal of Christian life and adaptation of ecclesiastical practice to the needs of this age, so that the witness of Faith may shine forth with new clarity amid the darknesses of this century.”

CWR: Nevertheless, underestimated problems emerged.

Seewald: Yes. Ratzinger became the Vatican Council’s spin doctor alongside the influential Cardinal from Cologne, who adopted all of his texts. The Curia had assumed that its submissions needed only to be rubber-stamped by the assembly of cardinals, and the council could be completed in a matter of weeks. Ratzinger was then involved in ensuring that the given agenda and predetermined processes could be broken up and everything renegotiated. Traditionalist in his basic attitude, but modern in habitus, language and orientation, he was able to gain recognition and a hearing in both the conservative and progressive camps. In retrospect, of course, he also realized the collateral damage he had caused with the uprising of the cardinals, which he had helped to incite, namely a “fateful ambiguity of the Council in the global public, the effects of which could not have been foreseen”. It gave impetus to those forces that regarded the Church as a political issue and knew how to instrumentalize the media. “More and more the impression was formed,” he noted at the time, “that actually nothing was fixed in the Church, that everything was up for revision.”

CWR: Near the end of this volume, you write, “Recent research shows that [Ratzinger’s] contribution [to the Council] was much greater than he himself revealed”

Seewald: This already began with the groundbreaking “Genovese Speech” of November 1961 and his appeal that the Church should discard what impedes the witness of Faith, from the expert reports on the schemata, in which he criticized the lack of ecumenism and pastoral style of speech, to the eleven major speeches for Cardinal Frings that brought the Council Hall to a boil. In addition, there was the textual work he did as a member of various council commissions.

As mentioned before, Ratzinger wrote the draft with which Frings, on November 14, 1962, brought about the overturning of the Council procedure established by the Curia. He was behind the November 21, 1962, dismissal of the schema on the Sources of Revelation, which he had criticized as being “frosty in tone, in fact, downright shocking.” That was the turning point. From that hour on, something new could happen, the true Council could begin. Joseph Ratzinger had thus a) defined the Council, b) moved it in a forward-looking direction, c) through his contributions had played a decisive role in shaping the results.

With Ratzinger’s contribution to Dei verbum, the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation – which, along with Nostra aetate, Gaudium et spes and Lumen gentium, is one of the keys of the Council – a new perspective opened up: away from an overly theoretical understanding of God’s revelation and toward a personal, historical understanding based on reconciliation and redemption.

CWR: Later it says in your biography: “The doors had barely shut on the last session when a Herculean task began for Ratzinger, a 50-year battle for the Council’s legacy.” What are the main features of his contributions and what he – as prefect for the CDF and as pope – sought to do in relationship to the Council?

Seewald: To be clear, the Council Fathers had not legitimized any rhetoric that would amount to a secularization of the Faith. Neither was celibacy shaken, nor was the priesthood of women envisaged. Neither was Latin banned from the liturgy, nor was there a call for priests to no longer celebrate Holy Mass facing ad orientem together with the people.

Nevertheless, it had become clear that the Vatican Council had strengthened forces that sensed an opportunity to jettison basic tenets of the Catholic Faith with the help of an ominous “spirit of the Council” to which they consistently referred. Ratzinger and his comrades-in-arms had underestimated that the desire for change could also develop into a desire to deconstruct the Catholic Church. And they had underestimated the influence of the media that were aiming for a systemic change in the Church.

For Ratzinger, therefore, a fifty-year struggle for the true legacy of the Council began. What John XXIII wanted, Ratzinger said, was precisely not an impulse for a watering down of the Faith, but an impulse for a “radicalization of the Faith.” He saw himself as a progressive theologian. However, being progressive was understood quite differently from today, namely, as the effort for a further development out of tradition – and not as empowerment by means of self-important self-creations. The search for the contemporary, he proclaimed, must never lead to the abandonment of the valid.

CWR: Finally, will there be one more volume in this biography? How is work going on that?

Seewald: The text for the second volume of the English edition is available. It has already been published in the German, Italian and Spanish editions. This second part takes us from the time of the Council and the collaboration with John Paul II to the pontificate of Benedict XVI and the years as Papa emeritus. It also reveals, in particular, the background to his resignation. I hope that Bloomsbury Press will be able to publish this volume soon.

(Translated from German by Frank Nitsche-Robinson. The theologian Eugen Drewermann was erroneously identified as “Jürgen Drewermann” in the interview; that error has been corrected.)

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

To read Pope Benedict XVI’s works is to encounter a heart and mind steeped in the love of Christ and the Church. His writing shines with a penetration, clarity and profundity inspired and schooled by personal and liturgical prayer, sacred scripture, and an intimate familiarity with the Fathers and Doctors of the Church; it also demonstrates a remarkable knowledge of history and the ideas that shape it. Pope Benedict is thus eminently placed and equipped to exercise searching and judicious discernment of the signs of the times in relation to the past and the Church’s mission in the present. Reading his works provides stimulus and opportunity for the integration of faith and reason that is distinctive of Catholic theology and necessary for the Church’s task of evangelising.

As the above interview indicates, the significance of his contribution to the Church and the modern world becomes increasingly recognisable as the inadequacy of contemporary secularism plays itself out in bizarre and extreme ways.

And not the least of his virtues is humility. We are indeed blessed to have him among us, and the legacy of his thought, witness and dedicated service.

Very true.

There is a factual error that needs correction in this insightful interview: the name of one of the two opponents is “Eugen Drewermann,” not “Jürgen Drewermann.” Hopefully, the article can be updated to reflect the correction of this error.

Thank you for pointing out the error. It has been corrected and a note added.

“They had underestimated the media that were aiming for a systemic change in the Church.”

Scary – and true.

And it’s going on today.

And it’s not just the media but well funded non profits.

What is of immediate interest to this reader is interviewer Carl Olson’s eliciting from Seewald his own life experience, and the insightful positive influence of Josef Ratzinger. Abhorrence to brutal Nazism is contrasted to love of his sensual mother. Focus on Beauty in Bonaventure shaped his thought and spirituality. Ratzinger finds Augustine much more personal than dry Aquinas. Josef senior the principled intellectual anti Nazi policeman is the apparent other influence. All of which brings to real life Ratzinger the CDF Panzer. Exacting regarding truth modified by his actual soft, gentle personality. A rare combination in an exceptional man.

Ratzinger per Seewald give us a needed correction of John XXIII, “He called it the Council’s task to transmit the doctrine purely and completely, without attenuations or distortion”. Seewald touches on the departure from intent of Ratzinger, the documents authors by Modernist “forces that sensed an opportunity”. Allegations since are that the latter introduced revisions into the documents that provided even greater opportunity. It’s of interest to know if that allegation has been confirmed. Whether true we remain with a Church of Christian pagans needing interior conversion to Christ. A judgment made decades past by Ratzinger. That is the quandary today with a Church becoming more incorporated in the world than in Christ.

Excellent. Thank you for the interview and for the discussion of “Entweltlichung” (lit.: de-worldization = detachment from worldliness). It was still his dominant theme during his September 2011 papal visit to his homeland. We ignore him at our peril.

Pope Benedict XVl played a huge role at the Council. He is now being blamed for beginning the destruction of the Church at the Council. Benedict had his views, he was sincere. But his liberalism caused great damage to the Council. Archbishop Vigano has pointed out how Pope Benedict, whom Vigano highly reveres, was part of the cause of the destruction of the Council that damaged the Church with unheard of proportions. Vigano states on the tossing out of the 9 original Schemata, “By what authority did they do this?”. Pope Benedict himself spoke of how he had taken a wrong turn, leaning towards liberalism. After the Council Pope Benedict speaks of how he saw what such erroneous thinking could do harm to the Church. He said he made a complete turnaround, and thus he became a great defender of the Holy Roman Catholic Faith. Pope Benedict XVl’s life is a powerful witness to being human and at the same time living the Supernatural life. Pope Benedicts story of his life is like reading the life of a Saint. One day he too I hope will declared a Doctor of the Church, maybe Patron Saint of those who seek God 100%, not part of God but all of God.

“Pope Benedict himself spoke of how he had taken a wrong turn, leaning towards liberalism. After the Council Pope Benedict speaks of how he saw what such erroneous thinking could do harm to the Church. He said he made a complete turnaround, and thus he became a great defender of the Holy Roman Catholic Faith.” Where did you take these words from ? Are these words from a book ? or an article ? Lou

Lou, Yes they are from both a book and he saying it before his resignation. The book is his Biography. Read the details from his biography on Rorate Coeli, Ratzinger and Vatican ll, they are his own words. In it he says he spearheaded the dumping of the 9 Schemata that St. Pope John XXlll had prepared. Pope Benedict says he wanted a different approach to the Council, different from the official 9 Schemata. I in no way condemn Pope Benedict XVl. He is revealing to us that something did in fact go wrong at Vatican ll. The Biography of Pope Benedict XVl justifies Archbishop Vigano’s call for declaring the Council illegitimate. Many, Many, things went wrong. Also Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre has been vindicated. I now maybe understand why St. John Paul the Great and Pope Benedict XVl held Lefebvre and his SSPX with such great importance. All 3 were at the Council, Lefebvre as a Council Father voiced out so many concerns at the Council. Such that at one Session of the Council he walked out yelling to all the Bishops, “You will destroy the Church!!!, You will destroy the Church!!!”, was he wrong?

“Pope Benedict himself spoke of how he had taken a wrong turn, leaning towards liberalism. After the Council Pope Benedict speaks of how he saw what such erroneous thinking could do harm to the Church. He said he made a complete turnaround, and thus he became a great defender of the Holy Roman Catholic Faith.” Where did you take these words from ? Are these words from a book ? or an article ? Lou

“Ratzinger and his comrades-in-arms had underestimated that the desire for change could also develop into a desire to deconstruct the Catholic Church.”

I’m curious what really was “The New Pagans and the Church” about? How one can be aware of the paganization of believers and underestimate them years later?

And which was the last Church event able to observe signs of times? Papal infallibility definition?

This article indicates in explicit terms that “the spirit of the council” is not something subsequent to VATICAN II; it was a formula that arose concurrently with the Council. Two things are suggested thereby to me. The first is that it was a catch-phrase rallying those who were seeking to establish or impart their own stylizations through the Council; and that this stylization has not stopped but continues on to this day. The second thing suggested to me is a little more subtle (if I may). This pursuit of stylization is not unique to the Council event; nor is it the unique result of the Council or of the convoking of the Council; nor is it dependent on the Council. It utilizes the Council for sure and it has a certain relentlessness going with it -or, sense of its own conviction. Incidentally, it can and does reveal its own weaknesses, falsehoods and artifice. In broad terms we can see that sometimes it will refer something from the Council and get it wrong; then sometimes it will refer something to the Council and get it wrong; and then sometimes it will not refer to the Council at all and get it wrong. The way to treat with it is not “strict traditionalism”. What is needed is prayer and prudence, faithfulness and understanding. For it is the case that our very lives and our encounters are a Christian unfolding that have to attain to their own goodness; and we can be very surely certain that offered with the Church, they will find their fulfillment and participate and be upheld, in the truth of the Fathers.

Elias Galy, When the Council is now spoken of I can’t take things about the Council seriously anymore. I completely agree with Archbishop Vigano that the Council must be declared illegitimate. The opening of the Council in October of 1962 was actually to finish the Council. The Council was completed and all the Bishops of the world took part. All the Bishops of the world were instructed to come to Rome to sign the 70 Decrees of Vatican ll. The Modernists planned well in advance to do away with the Council of St. Pope John XXlll. When the Council began it was the actual end of the very Council itself. The Modernists took over and garnished just enough votes to vote the real Council out. Vigano rightly asks, “By what authority, by what right did they do this?” The Modernists then went on to make their own Council. Jesus says, “know them by their fruits”, this includes a very Council itself. The Council was a battleground of Traditionalists VS Modernist heretics. We have had 60 years of destruction and it keeps getting worse. These are the fruits of the Hijacked Council. It shows that their Council was not ever Blessed by God. Bring back the 70 Decrees of the Council, the Vatican ll 1962 Missal, and the Apostolic Constitution on Latin. Then and only then can we have a “New Springtime” in the Church. Bring back the Council of St. Pope John XXlll so that the “windows of the Church be opened to let the fresh air in”. Make the modernists stop stifling God the Holy Ghost.

The fact that the neo-modernists interpreted the Council, both during and after, does not make it illegitimate. To me Dei Verbum is profoundly important as it is written, not as it has been interpreted by modernists biblical scholars and theologians after the council. We have the actual teachings of Our Lord recorded by eyewitnesses: what Jesus teaches and what Jesus did. Bishop Borromeo kept a dairy during the council and nailed it: there was a kind of neo-modernism at work in the Council that had the form of orthodoxy, but shifted the foundation of Church teachings from the Gospels, to a secular understanding of reality. We live with the consequences, but we have a clear picture of where this leads in our time. I have no doubt that remaining within the Mystical Body of Christ is the path to salvation.

Cognitive dissonance is the condition where one does not perceive 2 realities properly and as a result he is at cross-purposes in what he himself is asserting.

Andrew Angelo, the Church subsists in the Council and the Council subsists in the Church with no confliction.

For you to say that the Council must be rescinded means the Church is hobbled by the Council. The Church is not hobbled by the Council. So there.

Maybe you would like to say that the Council is revocable according to a putative assembly who would revoke. But the Church established the Council. So there.

If you spend all your time trying to realize some part or all of those mis-conceived visions, you either have no apotolate or your apostolate will ultimately be in vain. So there.

The Council dogmatically declared the BVM Mother of the Church. She herself will add to both dimensions what is due to them and we can depend on her “full of confidence” and we OWE HER THAT. So there.

I already told you how I pray for you and I already told you to make your prayers with me to go like incense YOU KNOW WHERE. So there.

‘ “More and more the impression was formed,” he noted at the time, “that actually nothing was fixed in the Church, that everything was up for revision.” ‘

When I read the Council documents I really get no sense that everything is or was up for revision. Paul VI is very clear about the Church engaging the age according to her very nature. For example, APOSTOLICAM ACUOSITATEM 14, laity must be good stewards of Christian wisdom. If, however, it is repressed, the repression is not happening “from VATICAN II”. This problem is a matter of who is speaking. First “strict traditionalism” or “absolutist traditionalism”, acts in a way that exacerbates the errors and divisions, quite as to help them by blaming VATICAN II not the perpetrators -very unjust. Second, generally there is the inevitable influences from concupiscence, worldliness, institutionalisms, poor instruction, party spirit, sin, etc. As a result adaptation is taken as authenticity. Or places fall apart over time. Third, the synods currently being held and those proposed for the near future seem to be not targeted on the right matters and so would not be geared to working out improvements. Likely they will make things worse. Fourth, there could be a need for an ordered hierarchical approach but it has become the norm to batch everyone together all at once; where pointing it out is thought to be “attacking the whole Body”. Fifth, frankly, many do not know the Council at all and many who would appreciate it, can not find the reception. There is a lot of excising and sidelining. Sometimes, humiliation. The Council was not supposed to be shut in behind the doors!

I am sorry to chatter so much, please accept my apology.

Insight into and direction with Benedict’s own thought can be found in VERBUM DOMINI and in ON THE WAY TO JESUS CHRIST; and here -:

https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2014/05/06/new-book-compiles-ratzingers-contributions-to-the-synod-of-bishops/

This is the material available to me so far. But I do not have the actual book by Eterovic.

I found the simple discussions in ON THE WAY TO JESUS CHRIST most helpful indeed.

Thank you for republishing this interview at this time. Long and informative, but maybe the takeaway nugget at the end best defines the special contribution of Benedict to the perennial and living Catholic Church, in addition to someday being recognized as a Doctor of the Church…

Seewald summarizes: “…being progressive was understood quite differently from today, namely, as the effort for a further development out of tradition – and not [!] as empowerment by means of self-important self-creations. The search for the contemporary, he proclaimed, must never lead to the abandonment of the valid.”

“The valid,” as developed and affirmed, for example, in the Magisterium’s Veritatis Splendor regarding moral absolutes. And not as likely [?] to be abandoned under the weather-vane logic of Cardinals Grech and Hollerich…in an adulterated synodal compendium or “synthesis,” with their signaled pretense to either displace or rhetorically sidestep the universal natural law on sexual morality and, too, even the Second Vatican Council itself with its “valid” and “contemporary” Catechism (given to the universal Church as “fruit of the Council).”

Most broadly, the tension between what is forever permanent in God, and the flow of human history, is found only in the concretely real and singular Incarnation of divinity into our history: “Jesus Christ, the same yesterday, today and forever” (Heb 13:8).

Thank you ! Interesting words of the Pope Emer. about ‘paganism’in the Church as far back as 1958 … ? Paganism in the sense of not knowing the True God , not knowing and loving His Holy and Divine Will, to live in same ..the love and honor he gave to St.Hannibale – having his statue at the Vatican , the connection of the St. to the Divine Will mystic S.G.Luisa and the related 24 hour Passion meditation in Germany – through the Benedectine monk Ludwig Beda – also from Bavaria . Interestingly the mystic and the Pope born in April – the month devoted to the Eucharist and Holy Spirit ,thus the Divine Will … both were baptised on the day they were born .

The Eucharist as The Lord’s sacrifice of His human will to the Divine Will – the Pope Emr. too having done same , having sacrificed his desire to lead a quieter life in Bavaria to instead take upon the difficult task of moving The Church deeper into the times for the Reign of the Divine Will – amidst the flood waters of the carnal rebellions – Germany not spared either .. ..

May his prayers along with the outpouring of same from world over help to usher in more of the newness of Life into many more hearts through the Queen of the Divine Will whose blessing has been again invoked by the Holy Father too .

https://queenofthedivinewill.org/luisa-and-the-benedictines/

http://luisapiccarreta.me/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/00%20The%20Twenty%20Four%20Hours%20of%20the%20Passion.pdf

Hoping that Mr. Seewald would share any anecdotes related to the above even if the Pope .Emer. may not have mentioned same explicitly- since good part of the related writings of the Book of Heaven are still under review at the Vatican AFIK .

Having grown bit jaded in attitude towards the St.Benedict medals / the St ., the talk by Rev.Fr.Jim might bless many to rekindle same ,including the narrative about a school in a Texas district that had become drug infested and poorly performing , brought back to be the best in the district in an year after exorcism prayers and use of the medals –

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=02-PxrCO88g

God Bless !