Rome Newsroom, Jul 28, 2021 / 03:00 am (CNA).

Hong Kong’s bishop-elect Stephen Chow has said that he wants to bring unity to his divided diocese when he assumes leadership later this year.

To achieve this goal, the incoming bishop will need to address differences among Catholics in Hong Kong, heightened by varying reactions to the local protest movement.

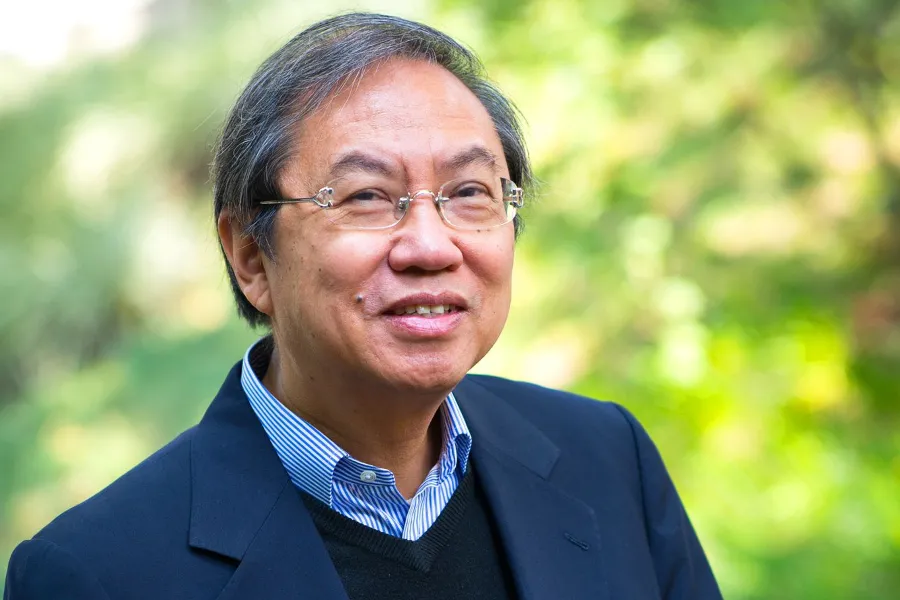

Joseph Cheng, a Hong Kong Catholic and retired political science professor, told CNA that Catholic institutions have been a major source of some of these divisions.

Hong Kong is a city filled with Catholic institutions, from hospitals to schools and universities. The universities, in particular, have formed a number of democracy activists, shaping the firm beliefs in justice and freedom that drove them into the streets.

But the desire to preserve these institutions has also led other Catholics to want to keep quiet, according to Cheng, who left Hong Kong in July 2020 and now lives in Auckland, New Zealand.

“The Catholic Church runs many important services for Hong Kong people, especially primary schools, secondary schools. Some of them are the most prestigious in Hong Kong in the territory. There are a number of hospitals and social service centers, welfare agencies run by the Church,” he said.

“Now all these service institutions are mainly funded by the government. So the Catholic Church in maintaining these services has to depend on financial support from the government. And there is a natural tendency … for these agencies to want to maintain an acceptable relationship with the government, a cooperative relationship with the government.”

This was not always the case, as the diocese of Hong Kong launched a suit against the government in 2004 after an amendment passed requiring “school-based management,” something that Cardinal Joseph Zen, the bishop of Hong Kong at the time, called a “conspiracy” by the government to take control of Catholic schools from the Church.

Other Catholics have responded to the dramatic changes that have occurred in Hong Kong since 2019 by entering into a “survival mode.”

Cheng said that many Catholics in the territory are middle class with good jobs and similarly have a tendency to accommodate the deteriorating situation.

“That is to say, well, since you can’t do much, you have to keep your head low. You have to simply accommodate, keep quiet, lie low, and survive,” he said.

“Then of course at the same time, many Catholics are idealists,” he noted. “They are concerned with the universal values that they cherish and they would like to uphold those values. They would like to continue to advocate social justice. They would like to continue to criticize the injustices that they see, the injustices of the authorities that they object to.”

More than a million people in Hong Kong, including a number of prominent Catholics, participated in pro-democracy protests of a controversial extradition law in 2019 and against the local government’s decision to push a national security law in 2020.

Jimmy Lai, the media tycoon imprisoned for his role in the pro-democracy movement, is a Catholic. But so too is Carrie Lam, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, who backed the contentious national security law.

Church leaders in Hong Kong are therefore faced with these broad divisions within the community, while recognizing that “solidarity is even more valued in times of difficulty,” Cheng said.

Chow, the incoming bishop of Hong Kong, is himself a product of decades of education, teaching, and administrative leadership in Catholic schools within and outside of Hong Kong.

The Jesuit bishop-elect has identified these tensions and divisions within Hong Kong and said at a press conference the day after his appointment that he thought that “listening and empathy” were very important to heal divisions, adding that “unity is not the same as uniformity.”

“I really have no big plan, grand plan of how to unify, but I do believe there is a God, and God wants us to be united,” the 61-year-old said.

Chow also told journalists that he did not think it would be wise to comment on especially controversial issues, particularly relating to China, the day after his appointment.

“That would be rash,” he said. “But it is not because I am afraid, but, I think, I believe that prudence is also a virtue.”

Nearly a year after the passage of the national security law, an official in the Vatican Secretariat of State said that he was not convinced that speaking out on the situation in Hong Kong “would make any difference whatever.”

Archbishop Paul Gallagher, the Vatican’s equivalent of a foreign minister, said: “One can say a lot of, shall we say, appropriate words that would be appreciated by the international press and by many parts of the world, but I — and, I think, many of my colleagues — have yet to be convinced that it would make any difference whatever.”

Hong Kong is at a turning point in its history, and Cheng believes that people will remember how the Church responded.

“This is a testing time,” he said, “And Hong Kong people, Chinese people, in the future will look back at these testing times and invariably they will say: What was the position of the Catholic Church? What was the position of the pope during these very difficult times?”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply