Rome Newsroom, Oct 21, 2021 / 06:05 am (CNA).

A canonization Mass is a global event, drawing thousands of people to the Vatican — the heart of the Catholic Church — to celebrate the pope’s declaration that a holy man or woman is a saint in heaven.

Like other large meetings around the world, canonizations have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions on travel and gatherings. And it remains unclear when the ceremonies can again safely take place.

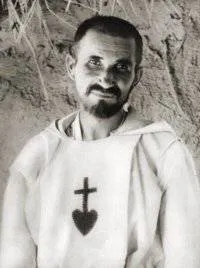

One of the canonizations on hold is that of Bl. Charles de Foucauld, a dissolute French soldier who became a Trappist monk and Catholic missionary to Muslims in Algeria. “Brother Charles,” as he was known to many, was killed in 1916 at the age of 58.

Pope Francis approved a miracle obtained through Foucauld’s intercession in May 2020, and the Church’s cardinals signed off on his and six other canonizations during a Vatican consistory a year later.

“Only the date is missing. It is the only thing missing,” Fr. Bernard Ardura, the postulator of Foucauld’s cause, told CNA last week about the canonization’s delay.

The Vatican is waiting for the global situation with COVID-19 to improve before it schedules the event, Ardura explained, noting that thousands of people from countries such as the United States, Canada, France, and Algeria traveled to Rome for Foucauld’s beatification in 2005.

Ardura, who is president of the Pontifical Committee for Historical Sciences, said that both he and Pope Francis hope the canonization can be held soon.

“Most recently we were thinking [the canonization would take place] around Christmas,” he said. “I told the pope, ‘So, we are waiting for this canonization?’ and he told me, ‘I want to do it! But…’”

“Canonizations are not for the saints, they are for us,” the priest said. “Because for them it changes nothing. It changes nothing for them. It is for us. It is a great ecclesial act.”

He suggested that the canonization would probably take place next year.

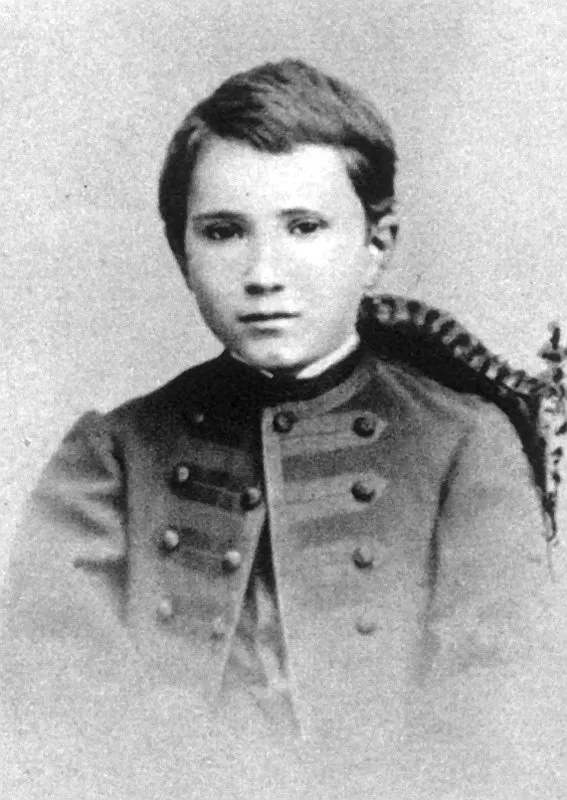

Foucauld was born in Strasbourg, France, in 1858. He was raised by his wealthy and aristocratic grandfather after being orphaned at the age of six.

He joined the French military, following in the footsteps of his grandfather. Having already lost his belief in the Catholic faith, as a young man he lived a life of indulgence and was known to have an immature sense of humor.

Foucauld resigned from the military at age 23, setting off on a dangerous exploration of Morocco. Contact with strong Muslim believers there challenged him, and he began to pray: “My God, if you exist, let me come to know you.”

He returned to France and, with the guidance of a priest, came back to his Catholic faith in 1886, at the age of 28.

Fr. Ardura said that after his reversion, Foucauld understood that “all of his life should be an imitation of the life of Jesus.”

“At the beginning, he thought he should imitate Jesus even materially. So he went to the Holy Land, and spent two years as a gardener in the convent of the Claretians in Jerusalem,” the postulator explained.

“Then little by little his faith matured,” Ardura continued. “And he understood that, yes, he should be an imitator of Jesus, but above all in that which Jesus is, in his actions; it is not necessary to go where Jesus lived geographically.”

At this point, Foucauld decided to join a Trappist monastery. Remembering his experience in Morocco before he returned to his Catholic faith, he desired, the priest said, “to be close to those who are poorest, the most disenfranchised.”

This is what led him to live among the Muslim Tuareg people, a nomadic ethnic group, in the desert of French-occupied Algeria.

“He decided to be an isolated, silent missionary, offering the witness of his life, of his presence, of his commitment to their service,” Adura said.

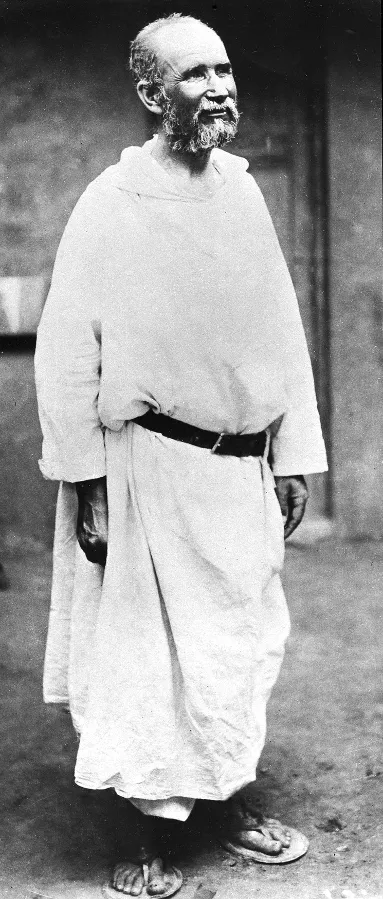

During his 13 years in the Sahara, Foucauld learned about Tuareg culture and language and compiled a Tuareg-French dictionary. The Tuareg people felt so loved by Brother Charles that when he was sick they cared for him in return.

The postulator explained that in Algeria, Foucauld found himself living between “two very different realities.” On one side, there were the French soldiers living in forts, many of whom were Catholic by birth but no longer believed in or practiced the faith. On the other side were Muslims, who were ritualistic but nonetheless an example of believers who took their religion seriously.

Foucauld’s approach, he said, was to speak “the language of charity.”

“He wanted to be the brother of everyone: beyond differences, even differences of religion, of culture, of language, etc., even differences in social situations,” Ardura noted. “Even if they do not know Him or they call Him by different names, there is one Father.”

“This is the essential lesson left to us today by Charles de Foucauld.”

Foucauld was assassinated by a band of men at his hermitage in the Sahara on Dec. 1, 1916.

Commenting on Foucauld’s great popularity among many Catholics and even some non-Christians, Ardura said he thought that people find the blessed attractive “because he presents himself as he is, without any particular decorum. He doesn’t pretend to play a role.”

The postulator pointed to some of the last photos taken of Foucauld before he died, when he was not even 60 years old, noting how he looks much older and even a bit rough around the edges.

“You no longer recognize the gentleman who once had so much success. It is as if his body lost some of its consistency, some of its beauty, and only his heart remains,” he said. “In him, we see Jesus, whom he wanted to imitate throughout his life.”

He continued: “‘Who is my neighbor?’ the young man asked Jesus. And Jesus responded by recounting the parable of the Good Samaritan. This illustrates the life of Charles de Foucauld: love your neighbor, be close to those around you. He did this by becoming the universal brother. He teaches us this, I think.”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

A few added comments:

First de Foucauld is to be contrasted with (not likened to) Muhammad. Both had been orphaned at eight, but de Foucauld’s turning point to the (Trinitarian) Faith came in a Paris confessional, rather than in a darkened cave echoing earlier caravan/fireside chats about a monotheistic Allah.

Second, among the Touareg people de Foucauld gained many converts, but he did this not by conquest (jihad) but by the witness of his personal poverty and simplicity.

Third, of missionary activity and, shall we say, the negation of “ideological colonization” (in the different Catholic Social Teaching), he said, “Neither does our role as Little Brothers include working for their adaptation to the Western materialistic, technological form of civilization, which, moreover, comes far from representing the only conceivable idea of a really human civilization” (cited in Rene Voillaume, “Seeds of the Desert,” 1964).

Fourth, regarding the deficiencies of generic, or only-fraternal (?) Christianity, Luigi Giussani recounts how Albert Schweitzer himself, an intelligent and profoundly dedicated humanitarian in Africa, questioned de Foucauld on how he received the level of love and devotion that he, Schweitzer, so dearly wanted? The difference was that while Charles did less, he lived more directly with his people as he shared his “certainty of hope” (!) in the ever-present Christ (citation from Gilbert Cesbron, 1952, in “Is it Possible to Live the Way?” 2008).

Thirty years ago I knelt in the empty confessional at the Église Saint-Augustin de Paris in which Blessed Charles made the confession marking definitively his conversion asking for myself the grace to return to the sacraments. Two years later it was accomplished. He surely was instrumental in “my miracle.” He was and is an extraordinary man, one I hope to see ever more widely known, and one to whom we can confidently provide our devotion. He is a saint for men.

The author left out an important truth stated repeatedly by Charles de Foucauld, one that might make his canonization uncomfortable for some people. Foucauld knew that only way that Arabs could ever be integrated into French society would be through Muslim conversion to Christianity. In other words, he recognized the folly of the notion of peaceful coexistence – at least on a national level – between these two cultures. Of course, he could not have foreseen the full extent of French apostasy and indifference in the face of a growing Islamic menace to Western Civilization.