Denver Newsroom, Feb 25, 2022 / 16:00 pm (CNA).

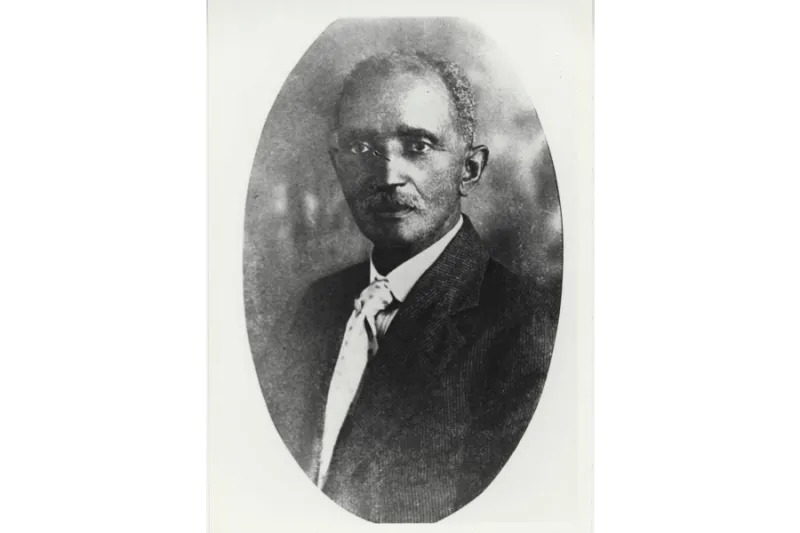

In the wake of the American Civil War, the former slave Daniel Rudd launched a newspaper that sought to inform his readers, advance racial equality, and convert the world to his Catholic faith.

“Daniel Rudd believed that the Catholic Church was the path to equality for Black people, and he published editorials in his newspaper, ‘The American Catholic Tribune,’ to that effect,” Valerie Washington, executive director of the National Black Catholic Congress, told CNA Feb. 23. “His beliefs, as published, reached not just Black Catholics at the time, but a large readership of White Catholics as well.”

Washington praised his efforts organizing Black Catholic leaders “to create discourse on the role of Black Catholics in the Catholic Church, and the issues impacting their ability to serve as full members of the Church.”

Rudd was born in Bardstown, Ky. to Catholic parents on Aug. 7, 1854. Though he and his parents were held in slavery, he seems to have been educated by a local Jesuit priest, Father John S. Verdin. He could read and speak German. After the Civil War, Rudd moved to Springfield, Ohio and became a member of St. Raphael Parish.

Perhaps his most prominent efforts came through journalism. By 1885 he had launched a weekly newspaper called The Ohio State Tribune, later renamed the American Catholic Tribune when Rudd moved to Cincinnati.

The Tribune carried news of the secular world and of other Black Americans, including an essay by Frederick Douglass. Rudd saw the newspaper, in part, as a way to show the Catholic Church as a place of racial equality.

“We will do what no other paper published by colored men has dared to do-give the great Catholic Church a hearing and show that it is worth of at least a fair consideration at the hands of our race, being as it is the only place on this continent where rich and poor, white and black, must drop prejudice at the threshold and go hand in hand to the altar,” he wrote.

Gary B. Agee, the author of two books on Rudd, told CNA Feb. 18 that the journalist “always just wanted a level playing field.”

Agee is the author of the forthcoming book “That We May Be One: Practicing Unity in a Divided Church” from the publisher Eerdmans. He is an affiliated faculty member at Anderson University’s School of Theology and Christian Ministry. Agee, a Protestant minister, is lead pastor at Beechwood Church of God in Camden, Ohio.

“There were some really ugly views of African Americans in this time and Rudd was able to negotiate and work and educate and agitate at times,” said Agee, who spoke at a December 2021 dedication of a historical marker outside St. Raphael Church. “I really tried to emphasize the difficulty of listening across boundaries and borders and then in recovering his legacy as someone who really did that, when it wasn’t easy,” he said.

“During his time in Cincinnati he sued an eatery that denied him the right to eat with a couple of his advertisers, who were white,” Agee said.

Rudd advocated for Blacks to be allowed to join labor unions, asked white Catholics to hire Blacks, and encouraged Black business owners to hire whites. He pushed for fair housing and opposed segregation in schools, hospitals, and other areas of American life. He specifically advocated for the hiring of Black firefighters in Cincinnati.

His work included organizing Black Catholics. In 1888 he led the call for a national group of Black Catholic men. The Archbishop of Cincinnati William Elder and Cardinal James Gibbons of Baltimore endorsed the effort, which became the Congress of Colored Catholics. The organization found some successes, including a meeting with U.S. President Grover Cleveland, but it would exist for only a few years. It is a forerunner to the National Black Catholic Congress, which launched in 1987.

To Catholic bishops of his time, Rudd made the case that Black Catholics had no one to act on their behalf. As an organized presence, they could work to support priests and to bring Blacks into the Church.

Another goal of Rudd, advocacy for justice issues, was much less popular and required a diplomatic approach.

He would argue against racists of his time, including other Catholics. But he considered racism among White Catholics to be an “Americanism” that did not reflect the universal Catholic Church, Agee said. He also faced obstacles in “paternalistic” attitudes. Would-be White allies could back job opportunities for Blacks and their ability to testify in court, but balked at social equality.

One exception was Archbishop John Ireland of St. Paul. His May 5, 1890 sermon at St. Augustine’s Church in Washington, D.C. condemned racial prejudice and the marginalization of Blacks. “Let Christians act out their religion, and there is no more race problem,” he said, insisting that Blacks and Whites “are both equally the children of a common Father, who is in heaven.”

Many Black Catholics welcomed Ireland’s homily, even when some of their own allies did not.

Despite some signs of social progress, Rudd’s work took place in a national environment that could be extremely hostile.

When Blacks became the victims of a wave of racist lynchings in 1892, he vocally opposed such murders. Rudd’s newspaper sold only in the northern states, Agee said. When one of Rudd’s employees traveled to Mississippi to sell newspapers, he too was almost lynched.

The circulation of the American Catholic Tribune peaked in 1892 at 10,000 copies per edition. A competing newspaper launched under Catholic auspices in Philadelphia, and subscriptions to Rudd’s newspaper dropped.

Agee suggested that Black Catholic advocates lost support from White Catholic leaders because they increasingly demanded that the Church live up to its own standards. For instance, the clergy told lay Catholics to send their children to parochial schools, but Catholic schools in many places did not allow Blacks.

Rudd’s own newspaper faced financial problems. He moved the newspaper to Detroit, but it folded in 1897 and he had to change careers.

He would go on to work under Scott Bond, a Black businessman in Arkansas who was an associate of the leading Black educator and self-help advocate Booker T. Washington.

Late in life, Rudd returned to Bardstown, Ky. and died on Dec. 3, 1933. His death certificate identifies him as a teacher. He is buried in the church cemetery of what is now the Basilica of St. Joseph, his childhood church. Then-Archbishop Joseph Kurtz of Louisville blessed an historic marker near his gravesite in 2020.

An historic preservation effort sought to preserve the site of Rudd’s death, the mansion house of the Anatok plantation which is now on the property of the Catholic Bethlehem High School. But demolition of the mansion began there Feb. 7.

The Archdiocese of Louisville voiced support for the high school’s decision to demolish the property, saying the property is unsafe, in disrepair, and has been the site of disturbances requiring police attention. The high school needs the space to increase enrollment and other needs of the school.

At the same time, the high school will create a memorial to Rudd at the mansion’s location.

“Rudd is a Black Catholic hero whose enslaved mother worked on this property,” the Louisville archdiocese said in a Feb. 9 statement, saying the school will seek to educate about “the sin of racism” and speak of Rudd’s contributions and “prophetic work.”

There are many other stories of advocates like Rudd.

“Rudd was only one of many African American Catholics that really contributed to the church,” Agee told CNA. “That’s something that we miss. It’s important for us not just to see Rudd as some kind of anomaly,” he said, citing the examples of Black Catholic advocates in Washington and in Philadelphia.

“There were a lot of folks that were doing this kind of thing. But then the climate changed with Jim Crow,” said Agee, referring to the racist system of state and local laws implemented in the late 1800s that blocked Blacks from advancement and equal participation in society.

Washington, the executive director of the National Black Catholic Congress, told CNA the organization sees Rudd as its founder. It has set up the Daniel Rudd Grant Program, which supports ministry to African-American Catholics, to honor “his legacy of ministry and support to the Black Catholic community.”

Washington noted that Black Catholics faced significant obstacles to being ordained or to participating in vowed religious life. She cited the example of Father Augustine Tolton, the first openly acknowledged Black American to be ordained a Catholic priest, who could not attend a seminary in the U.S. and had to go to Rome. Black women who faced obstacles in religious life would establish new orders, like the Oblate Sisters of Providence in Baltimore and the Sisters of the Holy Family in New Orleans.

For Washington, these “inspiring examples” led lives that “show that God’s will shall always prevail over the fears of people and their resistance to change.”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Leave a Reply