In 1832, responding to drastic social, political, and economic changes spreading chaos throughout society, Pope Gregory XVI issued Mirari Vos, “On Liberalism and Religious Indifferentism” — the first social encyclical. Previous encyclicals (letters by popes intended for general circulation) had addressed matters of faith and morals, or specific issues, such as usury in Vix Pervenit in 1745. Mirari Vos was the first encyclical to address an entire paradigm that Gregory and subsequent popes considered not merely “utterly foreign to Christian truth,” as Pope Pius XI put it later,1 but contrary to the universal principles of natural law “written in the hearts of all men.”2

Why, however, did the head of the Catholic Church take it upon himself to issue such a comprehensive document?

The Democratic Religion

Early nineteenth century society was in chaos following the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Age-old institutions, forms of government, organized religion, even marriage and family seemed dysfunctional. People began looking for new ways to address economic disparity, social inequality, and war.

What people got was nothing new, however, but a bundle of old heresies, rebranded as le démocratie religieuse, “the Democratic Religion.” This was a plan to remake the world into the image and likeness of a new deity and establish “the Kingdom of God on Earth.” The transcendent, absolute, supreme Being would be replaced with an immanent, conditional, subservient Becoming. God would be a divinized society. Religion would consist of the group’s worship of itself. Man would change from God-created to God-creator.

As described by Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon, in his posthumous 1825 book, Le Nouveau Christianisme (“The New Christianity”), the whole of society should be associated in one monolithic organization. There would be a total focus on material wellbeing, especially that of the poor. Private property, organized religion, and marriage and family would be abolished along with traditional concepts of God.3

Anticipating the World Economic Forum’s “Great Reset,” the social order would be organized into what Venerable Fulton Sheen called a “Religion without God.” It would be run by an industrial hierarchy, a secular priesthood that would replace traditional civil, religious, and parental authority.4

After Saint-Simon’s death, his apostles founded Le Église Saint-Simonienne (the Church of Saint-Simonism) to promote the teachings of their Revelator. They selected two Supreme Fathers, designed a special costume, and proceeded to shock Parisienne society with their outlandish theories, licentious behavior, and a drift into the Occult.5

Others followed the same program, almost to the letter. These included Charles Fourier and his Associationism, Albert Brisbane’s bowdlerized version of Fourier’s system, Étienne Cabet’s Icarian communism, Robert Owen’s socialism, Alphonse-Louis Constant (Éliphas Lévi Zahed) with his Universal Catholicism and ceremonial magic, and countless others. As Alexis de Tocqueville commented years later, there were a thousand different systems, each with its own prophet or messiah, but all coming under the common name of socialism.6

Socialism was intended from the start to be entirely separate from, and a replacement for, traditional Christianity. Adherents of the various socialist schools typically expressed varying degrees of hostility for the old religion, with special venom directed at the Catholic Church. G.K. Chesterton later noted that socialism is a fierce attack on Christianity from outside the Church.7

The Rise of Modernism

Chesterton added that, more subtle, and thus more dangerous, is the “treason” corrupting the Church from within8: modernism, the “synthesis of all heresies.”9 Modernism is not everything modern, but an attempt within Christianity to conform to the modern world based on personal interpretation of God’s law without regard to human reason.”

Originally called “Neo-Catholicism,” modernism began as an ultramontane movement under the leadership of Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre, to update the Church to meet the changing conditions of the modern world. There would be development of doctrine and more emphasis on immediate, temporal matters — what Pope Benedict XV would call doing “old things but in a new way.”10

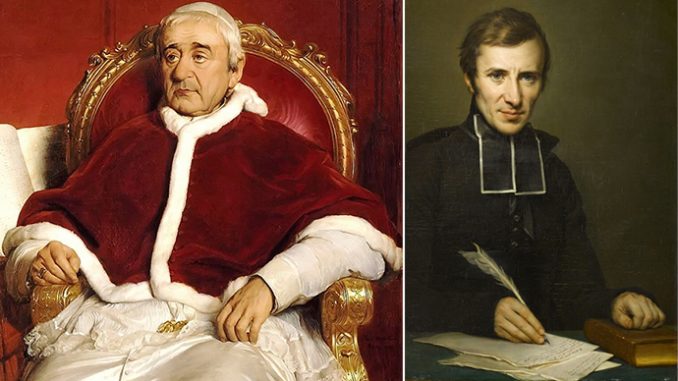

After de Maistre’s death in 1821, a Breton priest, Hugues-Félicité-Robert de Lamennais, assumed leadership of the movement. A true genius, de Lamannais was also an egotist with an unshakable faith in his own intellect. As de Tocqueville remarked after a run-in with him, de Lamennais had “a pride great enough to walk over the heads of kings and bid defiance to God.”11 Pope Leo XII thought about making him a cardinal, but reconsidered, commenting that de Lamennais’s fanaticism would, if left to itself, destroy the world.12

Charles Périn, who first used the term modernism in its Catholic sense, considered de Lamennais the first modernist. This was due to de Lamennais’s “theory of certitude,” which denied that God’s existence and the natural law can be known by individual human reason.13

Instead, de Lamennais asserted that humanity collectively reasons and thereby knows God and the natural law. Individuals can only accept God’s existence and moral absolutes on faith.

De Lamennais’s theory requires a supreme authority who, by divine right, has been given the power to interpret and promulgate this sensus communis. This authority, he argued, is the pope, who has absolute temporal and spiritual power.

Thus, socialism aims at separating organized religion from society and subsuming everything into a single form of organization the better to meet humanity’s material needs. Modernism’s goal is to make civil society subservient to religious society to enable the Church to meet the changing conditions of modern society.

In this way, socialism and modernism end up being two roads to the same destination. That is why Pius XI declared, “Religious socialism, Christian socialism, are contradictory terms; no one can be at the same time a good Catholic and a true socialist.”14

Socialism and modernism can be understood as the secular and religious aspects of shifting the basis of natural law from reason to faith. As Heinrich Rommen noted in his book, The Natural Law (1947), this leads inevitably to pure moral positivism and the belief that “might makes right.”15 It also promotes a form of liberal democracy contrary to Catholic teaching, in which, instead of the human person, the collective or an élite is sovereign.

The Pilgrims of God and Liberty

Energetic and industrious, de Lamennais worked to promote his vision of the Catholic Church and defend human dignity. In this he was joined by Charles Forbes René de Montalembert and Jean-Baptiste Henri Dominique Lacordaire, who later helped restore the Dominican Order in France.

Chief among de Lamannais’s projects was L’Avenir, “The Future,” a journal with the motto “God and Liberty” promoting his versions of Christianity and liberal democracy. It attracted some of the most noted Catholic intellectuals of the day, such as Blessed Antoine-Frédéric Ozanam, until its increasingly provocative tone and espousal of radical ideas alienated them. As Montalembert admitted years later, “To new and fair practical notions, honest in themselves, which have for the last twenty years been the daily bread of Catholic polemics, we had been foolish enough to add extreme and rash theories.”16

Running low on funds and facing harsh criticism from Church authorities, de Lamennais suspended publication of L’Avenir. At the suggestion of Lacordaire, the trio decided to go to Rome to appeal to the newly elected Gregory XVI. Calling themselves “the Pilgrims of God and Liberty,” de Lamennais, Montalembert, and Lacordaire set out for Rome in November 1831.

On their arrival in Rome, the Pilgrims were not granted an audience. This offended de Lamennais, even though the visit was unannounced and unsolicited.

Instead, the trio submitted a lengthy memorandum presenting their arguments. In late February 1832, Cardinal Secretary of State Bartolomeo Pacca let them know that the pope’s decision regarding de Lamennais’s theories would take some time, and they were free to return to France. He also informed them Gregory was not pleased with their activities, but they were free to continue them if they toned down the rhetoric.

This was more than enough for Montalembert and Lacordaire, but de Lamennais seemed deaf to Pacca’s polite, if unsubtle dismissal. He had not come for permission and a pat on the head, but enthusiastic support and endorsement. He continued lobbying until, finally, the three were granted an audience, but not on de Lamennais’s terms. Probably suspecting that de Lamennais would try to press the pope for a favorable decision on his theories, Pacca warned them not to raise any political issues.

Gregory received the men in a friendly manner in his private office. While impressed with their efforts to defend the Church in France (though not the manner of it), the pope pointedly confined the conversation to artistic and religious topics. Still, as His Holiness later remarked of de Lamennais, “That dangerous man deserved to be brought before the Holy Office.”17

After the meeting, de Lamennais continued to insist on an audience to discuss his theories and aired his grievances openly. Pacca chastised him for making private matters public.

At that point, Lacordaire, increasingly uneasy about de Lamennais’s intransigence, made a final, unsuccessful attempt to persuade him to return to France, then left Rome, alone. He continued to write to Montalembert, asking him to persuade de Lamennais to abandon his collectivist liberalism (the essence of the theory of certitude), and return to France.

The First Social Encyclical

None of the Pilgrims appeared to appreciate the difficult position into which they had put the pope. Powerful Gallicanists in France were urging Gregory to condemn all democratic principles, not just de Lamennais’s distortions of them. A blanket condemnation would have been contrary to Catholic doctrine, which recognizes the sovereignty and dignity of each human person, but not of the collective or an élite. Plus, it was a virtual certainty that condemning any type of democracy would likely have been applied erroneously to all forms.

At the same time, Gregory was dealing with the aftermath of the Polish “November Uprising” of November 29, 1830, to October 21, 1831. This began as a riot in which Polish collaborators and Russians were lynched during an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich and reassert Polish independence.18 This was something the pope would almost certainly have officially ignored except for two circumstances.

One, the Uprising became coupled with socialism, modernism, and the Occult. This was largely through the efforts of the anti-Catholic “New Christian” Ludwik Królikowski, “an ardent propagandist” for the Uprising who had associated with the Saint-Simonians while in Paris. Although the Uprising failed, it linked legitimate Polish nationalist aspirations to illegitimate religious and social concepts.19

Two, a renegade priest, Father Piotr Wojciech Ściegienny, had circulated a forged encyclical, Złota Książeczka (“The Golden Book”). In the pope’s name, people were urged to rise and destroy their presumed oppressors, including most priests and prelates of the Church, and redistribute their wealth.20

Especially in rural districts the forgery was accepted as genuine and circulated for years. It strongly influenced the development of socialism and popular understanding of Catholic social teaching in Poland. Among other things, it was a source for Mariavitism, a Polish heresy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that sought to establish the Kingdom of God on Earth.21 It is a tribute to the genius of Pope Saint John Paul II that as Bishop and then Cardinal Karol Józef Wojtyła he developed a Thomistic personalism that weeded socialism and erroneous versions of democracy out of Polish nationalism, and integrated authentic Catholic social teaching into the Solidarity movement.

Gregory obviously could not ignore either the attacks on Church doctrine and teachings by Królikowski and others or the usurpation of his authority by Fr. Ściegienny. Consequently, on June 9, 1832, he issued Cum Primum, “On Civil Obedience.” This was primarily directed at the Uprising, although he did not mention either Królikowski or the forged encyclical.

De Lamennais was infuriated at what he considered the pope’s betrayal of democracy. After letting his rage simmer for a few weeks, he left Rome in disgust in mid-August. A few days later, on August 15, 1832, Gregory issued Mirari Vos.

Ironically, the bulk of the encyclical is concerned with collectivist liberal doctrines — “novelties” — de Lamennais himself condemned, even as he applied versions of them in his own proposals. These included separation of Church and State, denial of the ultimate sovereignty of God, attacks on duly constituted authority (although de Lamennais disagreed that monarchy could be “duly constituted”), and freedom of conscience.

It is important to realize that some of these terms have both legitimate and illegitimate meanings, depending on the context. In the collectivist lexicon, for example, “separation of Church and State” does not mean religious and civil society have their proper spheres of authority, albeit with many areas of cooperation. Rather, it means organized religion has no place in society and is relegated exclusively to personal opinion.

In censuring “freedom of conscience,” the pope did not mean people can legitimately be coerced in religious matters, or that the State should enforce religious doctrine or practices. In context, “freedom of conscience” means all truth is relative. What is true in one set of circumstances or at one level of consciousness might not be true in another set of circumstances or at other levels of consciousness. What Gregory denounced was not religious freedom, but moral relativism — what Pius XI later condemned as “a species of moral, legal, and social modernism.”22

Rerum Novarum

De Lamennais’s reaction was not long in coming. On reading Mirari Vos, he told Montalembert it finished them, but that for the good of the Church, he would accept it. Not long afterwards, however, he expressed his real opinion in a series of intemperate letters. After one of the recipients made the contents public, Gregory demanded de Lamennais again submit.

De Lamennais complied, but almost immediately, possibly within hours, changed his mind. He repudiated his priesthood, renounced Christianity, and eventually established his own Religion of Humanity, with himself as supreme head.

Montalembert and Lacordaire attempted to argue with their former mentor, but to no avail. Lacordaire, especially, having adopted de Lamennais as his “spiritual father,” felt betrayed. He abandoned the effort to return de Lamennais to obedience and never spoke to him again. Montalembert continued for a few more years until it was painfully obvious that de Lamennais had no intention whatsoever of being dictated to by anyone.

His rage boiling over, in 1834 de Lamennais published a short pamphlet, Les Paroles d’un Croyant, “Words of a Believer.” In apocalyptic terms he denounced a conspiracy of kings and priests against the people. Virtually everything he had condemned as a Catholic he now endorsed, and vice versa. Translated into many languages, it sold tens of thousands of copies in a few weeks.

For nearly two centuries, adherents of liberalism have attempted to explain away the vitriol that permeates de Lamennais’s tract. There is, however, no disguising the malice it exudes against Christianity and the established order.

Unfortunately, many people even today have failed to realize that the collectivist liberalism espoused by de Lamennais is not the personalist liberalism consistent with Catholic teaching. They regard de Lamennais as the founder of liberal or social Catholicism, and a martyr to liberty.

Gregory responded to de Lamennais’s attack with the second social encyclical, Singulari Nos (“On the Errors of Lamennais”). After expressing sorrow at the apostasy of one for whom he had entertained great hopes, the pope condemned Les Paroles d’un Croyant as “small in size but great in evil.”23 He then proceeded to list certain problems with de Lamennais’s theories, referring to them as rerum novarum, “new things.”24

The Principle of Social Justice

Gregory’s reasoned arguments carried no weight either with de Lamennais or those swept away by the fervor of his rhetoric. Nevertheless, both he and his successor, Pope Pius IX, tried to counter de Lamennais’s emotion with empirical evidence and logical consistency. Nowhere was this more evident than in the work of Msgr. Luigi Aloysius Taparelli d’Azeglio, Gregory’s point man in the Thomist revival, which he viewed as the main response to the New Things.

In the 1830s a new term, “social justice,” had appeared. It was applied loosely to everything from fair administration of the legal system to socialist redistribution. Alert to the immense damage that errors in the social sciences can cause, in his 1840 work, Saggio Teoretico di Diritto Naturale (“Theoretical Essay on Natural Law”), Taparelli presented a more precise definition.

Not a particular virtue in the classical sense, Taparelli’s social justice was a principle directing individual virtue (habits of doing good) within a social context. As Taparelli construed social justice, it was the practice of individual virtue guided by the precepts of the natural law and the Magisterium of the Church, but always with an eye to the common good, that is, the effect of individual acts on others and society as a whole. It was not, and could never be, a substitute for individual justice or charity, or any form of socialism or modernism. Not understanding this, however, most people continued to use the term in its condemned socialist sense.

Pius IX continued Gregory’s efforts to counter the New Things with encyclicals and the 1864 Syllabus of Errors, but with indifferent success. His major effort, however, was the First Vatican Council.

Although the Vatican I’s work was cut short by the Franco-Prussian War, the Council Fathers defined two essential doctrines, papal infallibility, and the primacy of the intellect in matters pertaining to natural law. The combination completely refuted de Lamennais’s theory of certitude and the other New Things.

By limiting infallibility to faith and morals, and then only under certain conditions, the definition repudiated de Lamennais’s grossly exaggerated version of the doctrine. This was welcomed by those who, like Saint John Henry Newman, were worried that the Council would expand infallibility in a mistaken effort to overcome errors by fiat and assertion instead of by reason and argument.

Defining the primacy of the intellect made this even clearer. To counter the modernist and socialist reliance on faith as the basis of natural law, the Council declared denying that knowledge of God’s existence and of the natural law can be known by human reason alone is heretical. Pope Saint Pius X reiterated the primacy of the intellect in the first article of the Oath Against Modernism, while Pope Pius XII made it the basis of his argument in Humani Generis.

Intellectual arguments had little effect against socialism’s and modernism’s promise of a better life in the here and now, however. In 1891, therefore, Leo XIII issued Rerum Novarum, “On Capital and Labor.”

In common with previous efforts, Rerum Novarum condemned the New Things, but also presented a specific remedy for the evils of socialism: widespread capital ownership. As Leo stated, “The law . . . should favor ownership, and its policy should be to induce as many as possible of the people to become owners.”25

Endnotes:

1 Quadragesimo Anno, § 117.

2 Humani Generis, § 2.

3 “Saint-Simon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 19: 14th Edition, 1956, Print.

4 Ibid.

5 “Societary Theories,” The American Review: A Whig Journal, Vol. 1, No., 6, June 1848, 640.

6 Alexis de Tocqueville, The Recollections of Alexis de Tocqueville. Cleveland, Ohio: The World Publishing Company, 1959, 78-79.

7 G. K. Chesterton, Saint Thomas Aquinas: “The Dumb Ox”. New York: Image Books, 1956, 108.

8 Ibid.

9 Pascendi Dominici Gregis, § 39.

10 Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum, § 25.

11 De Tocqueville, Recollections, op. cit., 191.

12 Heinrich A. Rommen, The State in Catholic Thought: A Treatise in Political Philosophy. St. Louis, Missouri: B. Herder Book Company, 1947, 436n.

13 Charles Périn, Le Modernisme dans l’Église d’après les lettres inédites de Lamennais (Paris, 1881).

14 Quadragesimo Anno, § 120.

15 Heinrich A. Rommen, The Natural Law: A Study in Legal and Social History and Philosophy. Indianapolis, Indiana: Liberty Fund, Inc., 1998, 51-52.

16 Montalembert, from his Life of Lacordaire, quoted by John Henry Newman, “Note on Essay IV., The Fall of La Mennais,” Essays Critical and Historical. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1897, 173-174.

17 E. L. Woodward, Three Studies in European Conservatism, 265, quoted by Philip Spencer, Politics of Belief in Nineteenth-Century France. London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1954, 47.

18 Adam Zamoyski, The Polish Way: A Thousand-Year History of the Poles and Their Culture. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1994, 269-276.

19 Piotr Kuligowski (2018) “The Utopian Impulse and Searching for the Kingdom of God: Ludwik Królikowski’s (1799-1879) Romantic Utopianism in Transnational Perspective,” Slovêne 7, no. 2, 199–226.

20 Piotr Kuligowski, “Sword of Christ: Christian Inspirations of Polish Socialism Before the January Uprising,” Journal of Polish Education, Culture and Society, no. 1 (2012): 120.

21 Lukasz Liniewicz, “Mariavitism: Mystical, Social, National, A Polish Religious Answer to the Challenges of Modernity,” Master Thesis, School of Theology, Tilburg University, 2012/2013.

22 Ubi Arcano Dei Consilio, § 61.

23 Singulari Nos, § 2.

24 Ibid., § 8.

25 Rerum Novarum, § 46.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

I would argue that Lammenais was the composite of very active Jansenism. Later Lefebvre would encounter its more recessed form and find he could not work with it either.

A valid point — in “Enthusiasm” (1950), Msgr. Knox claimed that Jansenism and Quietism are both forms of “enthusiasm,” which IMO he used instead of the loaded term “modernism.” In my research I found that modernism by any name is far more pervasive than many people realize.

Greetings in the name of the Lord:

You touch on Jansenism, something that has its critics and proponents. As I understand, they view predestination as the correct pathway. Whereas the church views the subject as heretical.

If it is not too much trouble would you offer your perspective? A few verses that might give some credence to their perspective are as follow:

Ephesians 1:4-5 Even as he chose us in him before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and blameless before him. In love he predestined us for adoption as sons through Jesus Christ, according to the purpose of his will,

Ephesians 1:5 He predestined us for adoption as sons through Jesus Christ, according to the purpose of his will,

Romans 8:29 For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers.

Romans 8:28-30 And we know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose. For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified.

John 15:16 You did not choose me, but I chose you and appointed you that you should go and bear fruit and that your fruit should abide, so that whatever you ask the Father in my name, he may give it to you.

Thank you and God bless you as you strive to proclaim His glorious name.

Jansenism is a little out of my area, as I’m more focused on the post-French Revolutionary period and the rise of the “New Things.” I think Msgr. Ronald Knox’s analysis in “Enthusiasm” is probably the best around, and is much better than anything I could offer. I know it’s lengthy (unless you skip the parts you’re not directly interested in — in which case you miss the full context), but it’s well-written and in parts entertaining when you catch his little satiric insertions.

Thank you for noble work! Those who pursue scholarly tasks in spiritual matters are a blessing. When we know that our eternal soul rest safe in the arms of Jesus, we have the peace that passes all understanding.

Your response is respected and all that proclaim Jesus Christ in an academic setting add to our peace and understanding of God’s love.

Full appreciation

Thanks indeed for your interest.

The Church has been seeking to uphold Lefebvre and it is a fitting thing because of the fidelity that marked his life. My intuition is that this is central to reconciling the Lefebvrists – and history.

Lefebvre was able to identify Jansenism where he found it. It shows a rare clarity in understanding and his experience would contain valuable lessons for both his disciples and for the whole Church.

Heresy tends to affect whole groupings of society religious and lay and will persist down through generations. The arrival of a new heresy (eg., Modernism) doesn’t mean an earlier one (Jansenism) ended.

I have absolutely no idea what the current dialogue is with the SSPX what what long-term resolution is in mind. Looking back, it’ troublesome that Cardinal Baggio was interposed between the Holy See and Lefebvre.

Baggio of course being Freemason (another heresy), Lefebvre would have known that the interchange that was unfolding could never be ordinary or end in any norm. Once again he was exercising perspicuity that offends.

Thank you for your response. It is thought provoking and appreciated.

God bless you as you strive to proclaim His eternal truth.

Well done.

To borrow The Regina Academies mantra, “Faith without reason leads to superstition, and reason without faith to nihilism and rationalism.”

Mr. Greaney, thank you for a very informative and well-constructed article. Covers lots of ground prior to Rerum Novarum. Hopefully more such articles in the future…

Maybe even something that presents the depth of Mirari vos not only within the tradition of the later Rerum Novarum (the concluding citation about widespread ownership versus socialism), but, moreover, connects with what’s going on today as in the sinkhole “synodal way” of Germania…

August 15 of this year marks the 190th anniversary of Mirari vos, and some of its language, relevant to Germania (and others), might be this:

“The obedience due to bishops is destroyed […] Academics and universities resound with new and monstrous opinions, and no longer secretly or obscurely do they attack the Catholic faith [….] all legitimate power is menaced by an ever-approaching revolution-abyss of bottomless miseries, which these conspiring societies have especially dug, in which heresy and sects have so to speak vomited as into a sewer [!] all that their bosom holds of license, sacrilege and blasphemy.”

Again, the “synodal way.” A lot of water under the bridge—political, sociological and cultural—since 1832, but the watercourse of the “synodal way” is presciently identified in Mirari vos, and it’s not the Danube.

Very informative article. “The Council [1st Vat] declared denying that knowledge of God’s existence and of the natural law can be known by human reason alone is heretical” [M Greaney] is a paramount premise, as you cite Lamennais stating it required faith. Both Aristotle and Aquinas, as well as Moses, the Apostle in Rm 1, the Church have held both are accessible to reason, whereas it requires faith to efficaciously believe [some choose to believe devoid of faith, faith always a gift of the Holy Spirit evident in disposition to do God’s will] that Christ is the Son of God and exclusive Savior of Man.

To that point, Paul in Romans 1 made the case that the Gentile Romans were obliged to comply with what reason revealed in nature regarding the existence of God, and by their rejection incurred God’s punishment, a form of withdrawal from the soul that led to perversity, same sex behavior. Natural law is inherent as prescient knowledge in Man, the Natural Law Within written in Man’s heart, whereas reason is by nature inclined toward truth, and with that, inference leading to the existence of God.

Yes, I’ve gotten into some rather “lively” discussions on this point, with people insisting that because the Will (faith) has the primacy in supernatural matters, it necessarily has the primacy over the Intellect (reason) in natural matters. They didn’t realize they were accepting the basic premise of modernism, and usually ended up calling me a heretic. Or worse.

It’s a little bit like differential Calculus. The human intellect is capable of discovering the truth, but the very precise tipping point into actual faith is a theological virtue, a divine gift, and the flawed human will can obstruct (not cause) this event. Original sin casts a shadow over every step of the way.

As to belief in God it’s not an act of faith, and we must be clear on that. Insofar as faith in Christ, it’s not first arrived at in the intellect by steps of reason finally requiring faith. It’s actually the converse. The gift of faith, our willful assent of Jesus as Son of God is in consequence supported by reason.

Got it. Thank you. Yes, we have scientific reason and the case of Albert Einstein who believed in God, but not a personal God–which he understood very incompletely:

“The main source of the present-day conflicts between the spheres of religion and of science lies in the concept of a personal God [….] In their struggle for the ethical good [only], teachers of religion must have the stature to give up the doctrine of a personal God [revealed in the incarnate Jesus Christ], that is, to give up that source of fear and hope which in the past placed such vast power in the hands of priests. In their labors they will have to avail themselves of those forces which are capable of cultivating the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in humanity itself [….] After religious teachers accomplish the refining process indicated they will surely recognize with joy that true religion [but not supernatural faith] has been enobled and made more profound by scientific knowledge” (Out of My Later Years, 1950).

He goes on to note the error of thinking the Bible a scientific text (as opposed to Galileo, etc.), but also adds: “On the other hand, representatives of science have often made an attempt to arrive at fundamental judgments with respect to values and ends on the basis of scientific method, and in this way have set themselves in opposition to religion. These conflicts have all sprung from fatal errors.”

Dear pastor and brother in Christ:

As you plum the depths of scripture for truth and guidance, we readers (followers of Christ) are blessed. It brings to mind the riches of God passed along to His followers.

Too, what a blessing to know that our faith is no vain matter. God authors the subject and perfects it through the process of sanctification. To rejoice that He has chosen us and we affirm that amazing grace by saying “Thank you Lord”, in turn making us profitable servants.

Hebrews 12:2 looking to Jesus, the funder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is seated at the right hand of the throne of God.

Micah 7:7 But as for me, I will look to the Lord; I will wait for the God of my salvation; my God will hear me.

1 Peter 3:18 For Christ also suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive in the spirit,

1 Peter 2:23-24 When he was reviled, he did not revile in return; when he suffered, he did not threaten, but continued entrusting himself to him who judges justly. He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, that we might die to sin and live to righteousness. By his wounds you have been healed.

Hebrews 1:3 He is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power. After making purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high,

Thank you and God’s richest blessings,

Brian

Leo XIII’s encyclicals that preceded “Rerum Novarum” should be read first in order to understand it’s context.

Michael Greaney: You should do a series on all the social encyclicals of all the Popes till the present. It’s much needed today given how most Catholics have forgotten this important segment of the Church’s teaching, making it indeed “the Church’s best kept secret.” Many Catholics would rather be guided by their preferred political and partisan ideologies rather than the Social Teachings of the Church in living out the faith in the social and political arena. Also there is a selective focus or intentional twisting on receiving the Pope’s encyclicals. Examples are like most American Catholics received Paul VI’s “Humanae Vitae” while ignoring his social encyclical “Populorum Progressio.” Or take George Weigle and his neoliberal capitalist cohort’s twisting of John Paul II’s “Solicitudo Rei Socialis” to make it appear as an endorsement of neoliberal capitalism when in fact a close reading would expose this lie as the Pope equally critiques both capitalism and socialism. Sadly their sophistry became the standard American reading of JPII as the apostle of neoliberal capitalism. Or take Pope Francis now gloriously reigning. Many Catholics would rather believe the lies and falsehood crafted by the fossil fuel industry and promoted and spread by politicians and so-called scientists in their payroll labelling the cry for lifestyle and structural changes in the face of climate change emergency as alarmist and a hoax. These Catholics follows these climate change deniers and question and cast doubt on the competent climate scientists’ findings or Pope Francis’ social encyclical, “Laudato Si” and the sequel “Fratelli Tutti.”

“ There are five encyclicals that, taken together, make up a “crash course” in the fundamentals of Catholic Social Teaching (CST): Diuturnum Illud of 1881, on the origin of civil authority; Immortale Dei of 1885, on the Christian constitution of States; Libertas Praestantissimum of 1888, on true and false freedom; Sapientiae Christianae of 1890, on the duties of Christian citizens toward their states; and Rerum Novarum of 1891, on labor and capital — i.e., the rights and duties of owners and workers. These documents and others akin to them are contained in A Reader in Catholic Social Teaching, which I edited for Cluny Media, and which has become the basis for many book clubs and parish classes. The texts contained in this volume have been purged of their typos (plentiful in online sources) and, in some cases, corrected against the Latin originals”. -Dr. Peter Kwasniewski

https://www.lifesitenews.com/blogs/what-leo-xiii-can-teach-the-21st-century-about-money-freedom-and-church-and-state/

Thank you Josemaria for this reading material, you have abridged my work and I am very grateful. What is also good about this is that it will help me to get fortified up with good instruction when so many spiritual statements and spiritualizations are being emphasized and almost imposed, irrespective of context.

I was the first to comment, above, in this article by Greaney, concerning Lamennais. By this time I had already gotten the spelling of his name, wrong, in the article “What does it mean to reject VATICAN II?” (see link); and had aimed to get it right here. Yet nonetheless, I got it wrong again in spite of my sense of purpose. With names I have a dyslexia in the memory and it appears a dyslexia in the will as well!

https://www.catholicworldreport.com/2022/07/07/what-does-it-mean-to-reject-vatican-ii/