The poet, literary biographer, and Catholic spiritual writer, Paul Mariani published his last book of poems, Ordinary Time, in 2019. Much of it written in the aftermath of his recovery from a brain tumor, the volume radiated gratitude to our God for life, for his wife, and his grandchildren, a gratitude only deepened by the harsh, sometimes violent, childhood in Mineola, New York, from which Mariani had long ago escaped. I reviewed that volume when it first appeared. Soon after, I gave a lecture to the Catholic Artists Society, in New York, that further discussed Mariani’s work. As I boarded the train at Penn Station, that night, to return home, I did not know I was fleeing Manhattan only a few weeks before the city would shut down, along with the rest of the country and the world, as the corona virus pandemic descended.

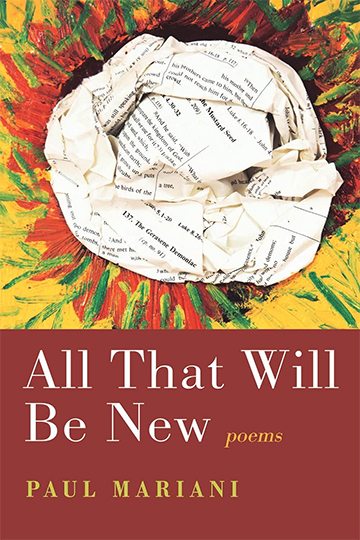

Three years on, and Mariani has published a new book of poems, All That Will Be New. Rumbling in the background of the volume, from beginning to end, are those events that have scored and dyed the last three years in our country’s life: the pandemic; the killing of George Floyd; the violent riots that overtook our cities, the anti-institutional sentiments that have swelled our provinces; and the general descent into partisan divisions of the nation as a whole.

Mariani’s previous volumes of poems were often touched, however gently, by recent events. As I noted a moment ago, the poems of Ordinary Time frequently express his gratitude for surviving a brain tumor; an earlier volume, Deaths & Transfigurations (2005), contains a good number of poems inspired by that inevitable moment, in one’s early old age, when friends and contemporaries begin to drop away. But, this new volume is shaped as a whole by these very recent events and, in contrast to Mariani’s other poems, it is the public history of our day as much as the private that informs the poems. For better and for worse, All That Will Be New comprises poems that are about, and for, and of our times.

The fine arts of their nature depend upon the act of sublimation or transformation. Our ancient ancestors expressed this by proclaiming Mnemosyne (Memory) the mother of the nine muses (the inspiring goddesses of the fine arts). Events occur in time; no sooner do they appear from the nonexistent future and manifest themselves as the present than they have already been carried off into the nonexistent past. Sunk as we are in the mutability of things, existence is momentary and thinner than the glassy surface of a pool of water. Before we can touch its sheen, we have already broken it. Thus it is, Hesiod and Homer, Plato and St. Augustine, all teach us that Memory allows what passes away to be gathered up and held together. Memory gives to what is always dissolving a place of timeless stability; it is from that deep and invisible place that the muses draw forth materials that will, finally, inspire the artist to give them manifest and permanent form. The arts give to passing events the permanent form of a story; they give to invisible, elusive ideas and wisdom permanent expression; they allow even the most evanescent of passions to strike us with an everlasting note.

What is true of all the arts has been true of Mariani’s poetry in particular. Mariani’s best-known poems are in what is generally called the confessional mode. The poems burrow deep into the memory of his past; they retell the events, and grapple towards understanding. They are works of recollection and reckoning. The shock of the confessional mode of poetry, when Robert Lowell and others inaugurated it in the 1950s, was the apparent absence of sublimation and the supposedly unfiltered, unformed, self-disclosure. But, as even a moment’s reflection on the classical idea of Mnemosyne reminds us, transformation is essential and also inevitable. Confessional poetry sometimes pretended that this transformation falsifies, but in fact it merely allows what passes away and would be otherwise unknowable to become something formed and permanent and intelligible.i What made much of Mariani’s work so compelling was his understanding of this. If many confessional poems merely shock with the—stylized—appearance of the raw, Mariani’s Catholic understanding of confession consistently sought truth, including that truth which escapes all appearing. As I have noted elsewhere, his confessions are those of Saint Augustine and not Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

The kind of sublimation we find in All That Will Be New is not exactly new in Mariani’s work, but it is distinctive. While one feels the constant presence and pressure in the poems of our recent public history, Mariani often finds ingenious ways to transform history into art, the violent passing of time into the stillness of poetic form. The opening poem indicates that this is exactly what Mariani intends. “Prologue: Northeaster at Prout’s Neck” begins with a vision of raw matter, utter mutability, a crashing sea:

The primordial tensions of those natural forces.

Watch, as the massive waves surge forward, then back

out of the vast Atlantic, as if sucked into some blueback

vortex, even as another wave and then another comes

crashing in to smash against the jagged granite shore.ii

We are set in that place of force, surge, crash, and vortex where nothing can stay. But, in the stanzas that follow, we are quickly informed it is not the sea we are looking at but a seascape of Winslow Homer’s. Homer the painter “caught the drama . . . back then,” (in 1895) just as Homer the poet “caught the drama” of the rage of Achilles nearly three thousand years earlier. And now, we can see it, the painting, where it “glowers in the cloister-like environs / of the New York Met, replete with a sleepy guard.”

As Mariani tells us, Homer caught other violent waves, including the cataclysm of the Civil War, the hard years of Reconstruction, and he sublimated the force of politics into the natural forces shown in seascape and landscape. So it will be “with the poet who must face the blank canvas // of the page and stare and stare and stare again.”iii Seven of the thirty-five poems in this collection directly take classic paintings for their subject. They are what are called ekphrastic poems: their explicit subject is a work of art, their meaning resonates far beyond the artwork.

The final two such poems consider paintings of Caravaggio—The Calling of St. Matthew and Supper at Emmaus—and this is significant. Caravaggio “was a brawler . . . And just how many he maimed / or killed or conned must be left for scholars to figure out.”iv He was also a singular painter and relied upon others, including the Pope, to recognize his talents and to pardon him his offenses—but this is no mere cunning. Caravaggio would include his visage in his own paintings and reveal “himself as one more member of the gang” that murdered Saint Ursula, “staring / down in disbelief at what his brushstrokes have revealed / about himself.”v That is one kind of sublimation, the kind that allows for turning upon oneself in moral reckoning. “Supper at Emmaus” depicts another sort:

And there’s that hand again, reaching out this time

to bless the bread that’s been set before him on the table.

It’s a small loaf, really, just a roll, and it’s been broken,

much as his body was three days before. To his left

there’s a pewter pitcher with black lines striped across

it and a glass half hidden, filled with bloodred wine.vi

The sacramental transformation of confession precedes the sacramental transformation of bread and wine into Christ’s Body and Blood—and these precede our own transformation, through the Eucharist, into the real presence, the mystical body of Christ.

In the best of these poems, we find kindred transformations. Jules Bastien-Lepage’s Poor Fauvette leads Mariani to meditate on the power of an innocent and earnest stare to strike our conscience, to lead us to moments of unguarded attention and communion:

Like the daughter of an old friend, himself long gone,

catching you in the frozen parking lot of the old brick

church just after Mass this morning, when all you

wanted was to climb inside your car for warmth,

her face and yours masked by this pandemic,

though her teary eyes spoke volumes as she began

to speak of the deep rifts between her brother and herself.vii

“The Wheel” recalls an uncanny episode in Mariani’s life, when he may have been spared a fatal car accident through the intervention of a guardian angel. He leads us from the steering wheel of the car and the saving angel to the turning wheel of Dante’s heavens, composed of the angels and the blessed saints: “That Force behind / those starry wheels that spin about the earth.”viii This is sublimation that is also sublime.

The volume comprehends other sorts of transformation. The summer of George Floyd leads Mariani back to an old favorite of his not especially known for the act of sublimation: the anti-poetic poet William Carlos Williams. Williams “wanted” to “Write about / the people close to me, to know them in detail, / the men and women and the kids playing . . .”ix Williams knew and, as a medical doctor, treated the modest and poor of Patterson, New Jersey. His life provides Mariani occasion to turn his own attentions to the meek and invisible among us. Williams was in his way a selfless poet, insofar as his poems are about “things,” but he could also be selfless as a doctor and provides an example of caritas.

Another poem on Williams, from which Mariani’s book takes its title, shows us Williams discovering that the true heart of America in the French Jesuit missionary Sebastain Rasles. Whereas the Puritan Cotton Mather dreamed of the “manifest destiny of New England,” Rasles made contact with the land itself and its native peoples, ate with them and “in the end would die with them.”x Williams, that most distinctly, baldly, obsessively American poet would thus conclude that the French Catholic more genuinely represented the history and spirit of the country. (It is almost as if America were a Catholic country.)

This reflection on the caritas of Williams and Rasles alike leads more or less naturally into three poems on African Americana: “A Brief History of Cotton,” “Harriett” (Tubman), and “That Morning after the Assassination of Malcolm X.” Here again is a reckoning with the meaning of the summer of 2020 through an indirection and sublimation that allows us to see the thing more fully and more clearly. They are not always successful poems, but they do show an effort to see into the permanent form of things.

Mariani’s style, as my quotations from the poems attests, has often been a colloquial one and, in that respect, follows the example of Williams. His most cherished poet (and the subject of more than one of his books), however, has always been Gerard Manley Hopkins. From the early poem, “Crossing Cocytus” to those collected in Deaths & Transfigurations, Mariani shows a capacity for the dense, awkward, richly jeweled and alliteratively playful language inspired by that poet. Deaths is Mariani’s greatest single collection precisely because of how fully, there, he marries his confessional subjects with a heightened poetic speech. All That Will Be New is comparatively plainer, despite a frequent use of long lines of rhymed quatrains and longer stanzas with irregular rhyme, and despite even a Dantesque vision poem of meeting his favorite poets, all told in a loose terza rima.

Given that most of Mariani’s strongest poems, in the past, have been those that dealt directly with his own youth and experiences as a young professor in New York, it is surprising to see that the least successful poems in this volume are those that, on the surface at least, seem similarly direct. Perhaps this is because the events involved are so near at hand that they cannot yet be handled without gloves. Perhaps there are degrees to which the transformations of Mnemosyne are necessary.

This weakness is evident in poems where Mariani’s language—questing after immediacy—feels like a recycling of the bebop language of the Beat poets, as when he proclaims, “Sing it, then, Homer, Hezekiah, Virgil. Sing!” or when he speaks of a pack of philosophers who once accosted S.T. Coleridge as “angel-headed hipster Danes.”xi There are too many “angel-headed” things altogether. At such moments, Mariani’s great resources fail him as he tries to represent the passions of our hour.

One poem, “Covid Boogie” fails particularly. Mariani has always treated with gravity his working-class origins and the great grace that allowed him to study, to enter the seminary for the priesthood, and eventually to attend graduate school and spend his life teaching the poets he loves. In much of his work, one gets the strong feeling that he is a poet and scholar whose heart idles in the empty lot behind his father’s filling station.xii But the passions of our hour, above all a general fear and partisan division, overwhelm him in this poem.

Writing in August 2020, long after the response to the George Floyd protests and riots had exposed as hollow all pretenses on the part of our public figures to contain the virus, Mariani nonetheless complains about “Three quarters of a million bikers, tattoo- / branded maskless bearded faces” descending on Sturgis, South Dakota.xiii “Masks, they sneer, are for dumb-ass liberals like me and you.”xiv He mocks a woman who refuses to wear a mask in a store for appealing to “the U.S.S. Constertution.”xv And, finally, the poem complains of college kids going to parties and then testing positive for the virus: “and it’s goodbye college, as all (or much of what) they hoped for dies.”xvi In another poem, he ridicules the “aspiring patriots” who would “make Amurka great again.”xvii

I understand the challenge here. The divisions in our time and place are real and the contempt running along the partisan divide is great. Having published a book-length poem on our shared—if also isolated and violently divided—experience of the epidemic myself, I think it is important to capture those divisions. But I also think it necessary to transform them, to distill them, to see into and also beyond them. Caricature is a kind of sublimation, and an important one at that, but it works only when we are certain that all there is to represent about someone is their vileness and absurdity. The problem of our day is not so much that people are contemptible, but rather that we as a people have lost every feeling except contempt. Some people would recommend we overcome this by way of “empathy,” but that is a lame word. How about “insight”?

Nearly all Mariani’s poems, over the course of a long career, testify to the insight that comes of sublimating even the most personal stories. His ekphrastic poems help us find, as it were, an objective canvas on which to inspect our private passions. Many other poems in this volume stare into the face of loss and find words to give loss permanent expression. I mention the failings in this poem only to set in relief and remind us of that glorious achievement when an artist, working with any material that is at hand, including the stuff of his own life, finds a way to give it form and permanence, to see all that has been and all that will be, and to see it anew.

All That Will Be New: Poems

By Paul Mariani

Slant Books, 2022

Hardcover/Paperback, 70 pages

Endotes:

i See Adam Kirsch, The Wounded Surgeon: Confession and Transformation in Six American Poets (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2005).

ii Paul Mariani, All That Will Be New, xi.

iii ibid., xi-xii.

iv ibid., 62.

v ibid., 63.

vi ibid. 67.

vii ibid., 7-8.

viii ibid., 66.

ix ibid., 28.

x ibid., 29.

xi ibid., 4, 23.

xii See, for instance, the essay “Class” in Paul Mariani, God and the Imagination (Athens: the University of Georgia Press, 2002), 15-29.

xiii All That Will Be New, 41.

xiv ibid., 42.

xv ibid., 41.

xvi ibid., 42.

xvii ibid., 64.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Sufficient time must elapse and space intervene before one can gain a proper perspective on the events of one’s life. Perhaps that’s what the Particular Judgment is all about: having gained sufficient time and space in death, God allows us to view our lives with a clarity never before possible – to know Truth as we never knew it before. If so, that will be a real eye-opener!

Sufficient time must elapse and space intervene before one can gain a proper perspective on the events of one’s life.

Yes! Absolutely, and hopefully pray that before the ‘Particular Judgement’, via the guidance/gifts of the Holy Spirit that the Truth of this eye-opening teaching will hold true and be earnestly desired by all Christians

“For every one that asks receives; and he that seeks finds; and to him that knocks it shall be opened To the reality of the selfhood/ego. (Now in the present moment)

Then seeing clearly, while now dwelling in humility we will then be able to say the words of this teaching and actually mean them

“So, you also, when you have done everything commanded of you, should say, “We are unworthy servants”

St Mother Teresa “If you are humble nothing will touch you neither praise nor disgrace, because you know what you are”

“Otherwise, having (Now) gained sufficient time and space in death”, you find the place of clarity “Where their worm does not die, and their fire is not quenched.”

kevin your brother

In Christ

My Brother:

So good to see your name and the peace of God that you bring to the discussion!

Arguably, poetry is the highest form of literature. We might turn to the Book of Job for inspiration.

Yet, to contemplate the music of Mozart, Haydn, Vivaldi, etc; poetic words from scripture in conjunction with melody is a great blessing.

2 Corinthians 9:8 And God is able to make all grace abound to you, so that having all sufficiency in all things at all times, you may abound in every good work.

James 1:25 But the one who looks into the perfect law, the law of liberty, and perseveres, being no hearer who forgets but a doer who acts, he will be blessed in his doing.

James 1:17 Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights with whom there is no variation or shadow due to change.

Numbers 6:24-26 The Lord bless you and keep you; the Lord make his face to shine upon you and be gracious to you; the Lord lift up his countenance upon you and give you peace.

Yours in Christ,

Brian

Thank you, Brian, my brother for your good-natured comment with scriptural blessings.

“Arguably, poetry is the highest form of literature I agree, and yes music can edify it, especially in relation to moral and religious knowledge while looking to scripture for inspiration.

Although beauty in all its forms can inspire and draw us closer to our Creator while not forgetting that ‘beauty’ is in the eye (Heart) of the beholder. An example is John Atkinson Grimshaw’s paintings which are significant to me as they stir up pensive memoirs such as the gas-lit Streets in which I played as a child in the City of Leeds in the North of England which were bleak nevertheless children adapted to harsh living conditions as reflected in these lines of poetry

Bumbling schoolboy having fun;

school over homeward run

New, cap on head, happiness in every tread

Dilapidated town, mean to the eye;

but not to a boy that wants to fly

A heathery down was this part of town

Booted feet, on clattering street

Clonking foot on hollow and soot…..

My penny catechism taught me that ‘God made me, to know Him’ so do not all true seekers of Truth no matter what their state of being, glorify God.

Many poets/searchers/seekers of truth have subverted the values of the world with a handful of words, and they could claim a share of these beautiful mystical words (which entranced me many years ago) by Francis Thompson

“Turn but a stone, and start a wing! ‘Tis ye, ‘tis your estranged faces, that miss the many-splendored thing”

For all true searchers, the pull of the Cross ‘draws us into His infinite beauty’ as it exposes the reality of sin, leading to the turning of stones/sins within our own hearts which stirs the wing (Higher consciousness) of the Holy Spirit to act (enlighten) while He endeavors to create a humble heart within us, His known dwelling place, without which our estranged hearts cannot truly see (Embrace) the wonder and beauty of our God in our neighbor and creation.

kevin your brother

In Christ

Dear brother:

A ray of sunshine to hear from you!

Francis Thompson, The Hound of Heaven! I have a friend who is a bookseller and purveyor of art. An interesting man of the world with strong opinions. Have mentioned that the hound of heaven is on his trail, he agrees yet, is resistant to the gospel message.

If Christ didn’t come and get us, where would we be and yet, some find the idea controversial! Perhaps a topic for another time. Speaking of discussions that can generate some crossfire, was reading Peter the other day. He is a man that God uses to bless many. What a thorough change in his life through his encounters with Jesus. Our sanctification process is often gruelling. Thanks be to God!

1 Peter 1:3 Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ! According to his great mercy, he has caused us to be born again to a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead,

A weighty thought for man to ponder. Yet it does not stand in isolation.

John 3:3 Jesus answered him, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born again he cannot see the kingdom of God.”

Ezekiel 11:19 And I will give them one heart, and a new spirit I will put within them. I will remove the heart of stone from their flesh and give them a heart of flesh,

John 16:12 “I still have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now.

Deep appreciation for what the Lord is doing in your life and what a blessing it is to others.

In Christ’s glorious name,

Brian

Addendum to my post above directed at Deacon Edward Peitler

“To know Truth as we never knew it before. If so, that will be a real eye-opener!

Rather it will be purgatory to face the fire (Of Truth) that the majority of us must face, which will be the completion of redeeming grace.

kevin your brother

In Christ

That’s an absolute fact. I speak from personal experience.

A most informative post Kevin. As always your poems are a pleasure to read. I hadn’t heard of the Poet Francis Thompson. I’ve just had the joy of reading The Hound of Heaven. Beautiful. I’m going to look further into this poets life.

Thank you for the introduction.

Blessings always.

Thank you Hannan for your supportive comment. I was unaware for many years where these words originated from “Turn but a stone and start a wing! ‘Tis ye, ‘tis your estranged faces, that miss the many-splendored thing” that is until a few years ago, so I was most pleased that I was able to introduce and share the writings of Francis Thompson with you.

So yes Hannan, Blessings as always

kevin your brother

In Christ

Dear Kevin. Since my last comment I have researched (as much as is available) a great many things on Francis. Some things I discovered were nearer to home than I could have imagined. I’ve also introduced Francis Thompson to a wonderful Priest in America who I am in touch with. All thanks to you!

Servus

Hannah