Christopher Dawson, though he never earned the doctorate nor held a permanent university post, was recognized in his day as one of Europe’s most profound thinkers. He delivered the Gifford Lectures in 1947, he served as editor of the Dublin Review, and he held the Stillman Chair for Catholic Studies at Harvard University. But Dawson’s standing today, a half-century after his death in 1970, speaks more of the state of contemporary culture and religion—the two chief focuses of his work—than of his dozens of books and countless essays. Among those who have no interest in religion or the spiritual forces within culture, Dawson is a nonentity, forgotten with the passage of time. By contrast, among certain types of Catholics who long for a more religion-friendly society, Dawson is a hero who articulates a vision dear to their hearts.

But Dawson’s vision is far too broad and too deep to be enlisted for sectarian or partisan battles. This fact is another reason for many to forget Dawson: since both his vision and his style of historiography transcend typical categories and myopic specializations, it is easier to throw him to the side rather than engage his formidable ideas.

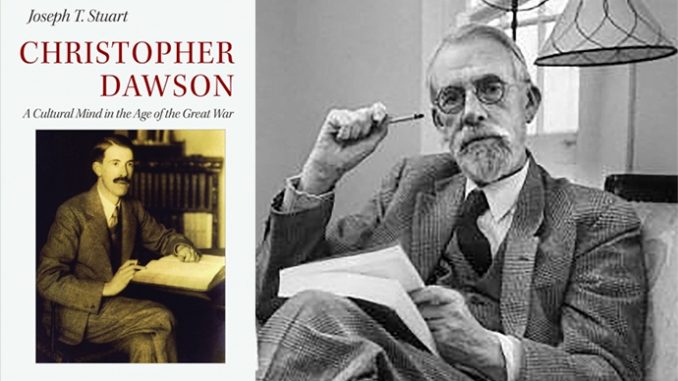

How Dawson—who wrote history shaped by sociological, anthropological, and metaphysical insights—developed his vision of culture as the reflection of peoples, and of religion as the heart of culture, is the subject of Joseph T. Stuart’s meticulously researched and carefully organized book Christopher Dawson: A Cultural Mind in the Age of the Great War. Stuart labels his work a “biographical study” that probes how Dawson came to think about culture, which he understood “simply as the common way of life of a people, including their vision of reality.” Dawson possessed a “cultural mind,” which Stuart characterizes as looking “at the world through the lens of culture, connecting ideas and social ways of life” in order to see the many facets of history in light of their whole. The culture of a given time, place, and people anchored Dawson’s historiography. He never once wrote a history that turned on a national or political axis.

Stuart’s focus on how Dawson first formed and later applied his cultural mind is his unique contribution to the field of Dawson studies, which have to date focused primarily on the man and his work. By showing how Dawson’s books and essays came to be, Stuart not only illuminates the enduring value of Dawson’s insights, but he also makes the case for how and why culture should serve as an essential component of historical thinking.

Dawson’s cultural mind, Stuart argues, was shaped by the cultural fallout of the Great War. Acutely aware of how the war and its subsequent years of political and societal turmoil “seemed to unmoor the present from the past,” Dawson “saw the crisis of the modern world as the result of the denial of spiritual reality, the loss of contact between religion and culture, the loss of the humanist tradition,” and the unmooring of human society from nature. While other thinkers turned to theology, philosophy, or literature for answers, Dawson turned to the new fields of anthropology and sociology, academic territory into which Catholics had not ventured before him.

Dawson was convinced that studying culture with the help of these new social sciences was the best approach for the historian. He rejected Arnold Toynbee’s multi-volume A Study of History because, in Stuart’s image, it employs the telescope to study civilizations rather than the microscope needed to understand cultures. As Dawson wrote,

The higher civilizations usually represent a fusion of at least two independent traditions of culture…. [T]he essential basis of the study of history must be, not just a comparative study of the higher civilizations, but a study of their constituent cultures, and here we must follow, not the grand synoptic method of the philosophers of history, but the more laborious and meticulous scientific technique of the social anthropologists.

Stuart breaks new ground in tracing how Dawson came to the fields of sociology, anthropology, and comparative religions, and how he meshed what he learned from them with eternal metaphysical and theological truths to form his “science of culture.” Critically, Dawson balanced two “modes” of cultural thinking. Stuart calls the first the “socio-historical” mode that is descriptive of cultures as phenomena unique to themselves; in this way, Dawson worked as a sociologist offering analysis in the style of Durkheim and Weber to show “how cultures are.” He calls the second mode “humanistic,” and it is prescriptive in nature, seeking the truths of “how culture should be.”

The two modes gave Dawson a perspective that few share. Dawson’s “transdisciplinary thinking” worked symphonically because of the discipline engendered by the “four rules of the cultural mind”—an “intellectual architecture” that situates new knowledge and facts in light of a broader whole; “boundary thinking” that sees both the integrity and the limits of different disciplines; “intellectual bridges” that form the intellectual architecture by bringing together what boundary thinking distinguishes; and “intellectual ascetism” that connects “factual fastidiousness, ideological restraint, and English reserve to clear writing” that did not serve “Catholic triumphalism or pedantry or political ideology.”

One crucial attribute that the two modes of cultural thinking and the four rules gave Dawson was what Stuart terms a “moderate cultural relativism,” which helped him see that, when studying culture, “‘universal’ and ‘particular’ present a false dichotomy.” For Dawson, the field of comparative religion links theological truths with local manifestations of belief so that the two are not antagonistic, but complementary.

It is with the book’s second part, the “application of a cultural mind,” that we clearly see Dawson’s continued relevance to contemporary historiography, culture, and politics. This relevance stems largely from Dawson’s sociological thinking, which is brilliantly analyzed by Stuart. Dawson, he explains, adapted Patrick Geddes’s environmental sociology that studied how human populations both affect and are affected by their geographic and economic situations. People, economics, and geography, rendered with the shorthand “FWP” (“folk, work, place”) are also heavily influenced by ideas, Dawson argued, and the key idea animating every culture is its dominant religion. “The spiritual faith and ideals of a man or a society—their ultimate attitude toward life—colour all their thought and action and make them what they are,” Dawson wrote in 1920. Religion, in other words, is “the key of history.” Hence Stuart summarizes Dawson’s “environmental sociology” with a schema that took a giant leap past that of Geddes: I/FWP, with the “I” being “ideas.”

This sociological framework is the key ingredient, Stuart argues, for Dawson’s penetrating insights into Europe’s post-war totalitarian movements that became “political religions,” that is, “movements ascribing ultimate values to the political realm…that take on some of the functional apparatus of religion.” In fact, the “secularization” that is used to describe the West’s slow rejection of Christianity “fosters conditions conducive to the sacralization of temporal realities.” These political religions have changed their smells and bells in the ensuing decades, but, from Communism to Wokeism, they have maintained a similar creed. Because he penetrates to the essential motives and claims of political religions, Dawson’s analysis reads as if it were written yesterday.

Stuart’s most provocative chapter considers the second application of Dawson’s cultural mind: the educational plan of “Christian studies” he developed for American schools and universities in the 1950s. Here Stuart himself applies Dawson’s cultural mind and I/FWP sociological schemata to explain how and why Dawson’s plan, which called for an integration of knowledge within a broader vision of Christian culture and a balancing of theological and philosophical studies with courses in the social sciences, was rejected by the pre-conciliar American Catholic establishment. To American Catholics finally integrating into public life, Dawson’s Christian culture “seemed a throwback to an older cultural pattern derided as the ‘ghetto’ by the rising Catholic middle class seeking to leave all that behind.”

In a theory that will rankle staunch supporters of Catholic universities’ former commitment to multiple courses in philosophy and theology, Stuart argues that had American Catholics adopted Dawson’s educational ideas and “moderate cultural relativism,” they would have prevented the social and institutional Catholic collapse that followed Vatican II but was already afoot with intellectual and sociological changes occurring in American Catholicism in the 1950s. “[W]ithout grounding in history and a moderate cultural relativism informing an understanding of doctrinal development in the church,” philosophy and theology taught as ahistorical universals led to “a reaction among the younger generation, and naiveté about enculturating the next generation.” Today, in the wreckage of Christian culture in America, few Catholic universities offer this former course of studies. But an increasing number of universities, including Stuart’s own University of Mary, offer Dawson-inspired Catholic studies programs that include philosophy courses within a larger sequence of courses in the humanities and social sciences.

Today, with many Catholic universities indistinguishable from their secular counterparts, with the humanities captive to ideological thinking, and with increasing scholarly focus that seeks to transcend disciplinary limits, Dawson’s idea of culture, concludes Stuart, offers “an itinerary for coordinating research in consideration of the whole, human picture” and “is capable of connecting to permanent things, normative outlooks, and life-guiding values.”

In other words, Dawson teaches us that culture is the measure of all things, and we would be foolish not to invite Dawson to help us measure.

Christopher Dawson: A Cultural Mind in the Age of the Great War

By Joseph T. Stuart

Catholic University of America Press, 2022

Paperback, 448 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Article about Dawson and Stuart himself very interesting. Am changing subject somewhat, but my admiration for John XXIII in part stems from fact he was church historian plus a Hebrew student. Added to his deep spiritually, he moved with this profound sense of divine providence. We need a new John.

This looks like a fantastic book. Whatever cultures flourished in the past, the growth of the “multi-cultural” mindset, which I believe has morphed into “diversity” is the death-knell of authentic, organic, religion-based culture. Now, customs (the frothy top-layer of cultures) are packaged in boutique fashion, displaying rituals as mere artifacts to compare in a kitschy sort of way (“Ooh, we have seven fish on Christmas Eve,” or “We always wear green on Saint Patrick’s”) and the only buzzkill in the conversation is that the deeper roots of ONE custom or another are somehow TRUE.

Diversity of organic cultures is a marvel in the history of mankind, but diversity as a present-day ideology crushes all momentum to allow any authentic life-giving culture to flourish. Looking forward to reading this, thanks!

I am getting the book.

I have 1 or 2 of Dawson’s books (in paperback), explaining the life of local Catholic cultures of English and Irish places and their survival against the onslaught of war from the predatory Vikings and other war cults.

The account of the modern age and its culmination in the 20th century idolatry of nationalism rings true. It not only happened in “Great Britain” and Europe and Japan etc; it happened in the United States, a global contest of “all-demanding-sacred-states.”

I will never forget the moment, some 30-40 years I guess, when I heard Chris Matthews doing his nightly commentary and expressing his astonishment that some Christians put their devotion to God before their devotion to the USA (I cannot recall, but he may have been specifically focused on Catholics).

We were assigned Dawson’s “The Making of Europe” when I was a college sophomore studying the Medieval period. It was one book that made a lasting impression on me.

If politics is everything [Charles Krauthammer] because it touches every dimension of human life, religion is everything because it directs history. Although religion can lose its directive effectiveness if it flounders intellectually.

Evidence of Dawson’s warnings targeted by Stuart [here per Bonagura], that “Catholic universities’ former commitment to multiple courses in philosophy and theology, Stuart argues had American Catholics adopted Dawson’s educational ideas and ‘moderate cultural relativism’ – they would have prevented the social and institutional Catholic collapse that followed Vatican II”.

Precisely my experience when entering higher studies, philosophy and theology was presented as a hodgepodge of equally relevant ideas [presented] in the name of religious liberty [or conscientious freedom for that matter]. Land O Lakes, Fr Hesburgh’s legacy had much to add to the intellectual [general] demise of Catholicism.

Christopher Dawson a genius, a philosopher of history and culture gave the diagram for intellectual development, his “intellectual architecture” that processed new ideas in accord with what this writer perceives as an integral right reasoning – thought developed and assessing transient or more permanent novelty from the parameters of permanent principles.

God who created the intellect for man didn’t intend that it flounder in a morass of competing ideas. The historical standard of permanent principles in philosophy and theology have been attacked as confining thought [example, in current Catholic thought the disputation of whether there are moral absolutes as contended in Amoris Laetitia] in the world of academia, now with Church hierarchy the pontiff himself labeling this as “crystallization” [of the Gospels].

I admire Christopher Dawson, who, along with personal experiences, was among the constellation of influential minds that affected my conversion from atheism to Catholicism. Yet I did look elsewhere for apologists who seemed less confident in the liberal tradition that holds so much faith in disciplined and truthful academics producing greater cultural stability. It’s so easy to lose sight of the pervasive reality and consequences of original sin.

My early studies in freshman philosophy in the “countercultural 60s” valued Plato’s emphasis on objective truth but recoiled at his notion of the philosopher king, an instinct that continued throughout my life into an appreciation for Trump’s hostility towards elitism. When near everyone in the world who thinks they are intelligent thinks you are stupid, you must be embracing and promoting something very noble and very truthful.

Does a mind motivated by sin leapfrog over competent education just as easy as a mind poorly educated? I used to think not, but the more I learn about current Church events, especially the behavior of high prelates who have come forward as enthusiastically supportive of “evolving thought” that actually contradicts its point of origin, or the fact that just as many “Catholics” support abortion as non-Catholics, or a Pope who is charged first with defending the Deposit of Faith but first insults those who defend it, and cannot perform such tasks as making a rational connection between the act of abortion, for which he claims to despise, and the sinful ethos of the sex revolution, for which he suggests we turn a blind eye, the more I know the connection between virtue and inheritance can only be by example.

Very good, EJB, but I think we can dial it back a bit further. Given the corrosive effect of sin on the intellect, we must believe that ignoring the first few commandments will impair one’s judgement—allowing him to transgress the rest. We express a horror at abortion while shrugging over neglect of the Sabbath, when it’s all of a piece.

“[T]he essential basis of the study of history must be, not just a comparative study of the higher civilizations, but a study of their constituent cultures, and here we must follow, not the grand synoptic method of the philosophers of history, but the more laborious and meticulous scientific technique of the social anthropologists.”

Sounds to me like Dawson was doing Annales style social history before Bloch and Lefebvre. Hmmm.

Dawson calls for “Intellectual asceticism that connects factual fastidiousness, ideological restraint, and English reserve to clear writing that did not serve Catholic triumphalism or pedantry or political ideology”.

Britain, with a long history of empire contact with multiple cultures, academically versed in the Greek and Roman classics developed a greater sense of holding back opinion until reaching reasonable certitude. Unlike Americans, builders and doers, more apt to make quick judgments. Social anthropologists Claude Levi-Strauss, Malinowski et al were making discoveries, Levi-Strauss cross cultural dynamics that speak to a deeper appreciation of human nature.

Academia in Britain had a greater field of reference and developed that intellectual asceticism Dawson required for true scholarship. In philosophy, we find that in the methodology in St Thomas Aquinas, who followed the Paris U system of question and answering debates seen in his writing constantly referencing various philosophical theological opinions [including Islamic Ibn Sina, Ibn Rushd] evident in the Summa Theologiae and elsewhere. Cicero [Tullius] one of the earliest political philosophers who firmly established principles of natural law by observation of similarities in Justice in Greece and in Rome.

Wisdom, as perceived in sacred scripture, perceived the wise man traveling abroad studying among various cultures, laws, principles of justice, the common good. Natural law is evident by observation and study of those cross cultural similarities we find expressed in what Aquinas calls the Natural Law Within, that universal sense of justice man shares by his created nature as ordained by God, the undergirding of conscience and right reason.

That is why Aquinas remains indispensable to theology [and reason in general or philosophy], the pursuit of truth, because he identified those coordinates by which reason is contained [Dawson] toward its proper end, which is truth.

Agree. The unique greatness of St. Thomas lies in the astonishing union that he achieves between doctrine and charity, between wisdom and holiness, between instructing one’s neighbor and learning from God. He has a medicinal or therapeutic conception of doctrine. When it comes to heresies, he does not get heated or indignant, as certain preachers do in whom anger prevails over mental clarity, thus endangering charity because charity is born only from the truth. Still, Thomas assumes the seriousness and calm of the doctor, who diagnoses the disease and prescribes the treatment.

Great minds, another gift from the Almighty. Energy well spent and developing a good memory, once more, assets from God. Anything we have that is favourable is from God. The best gain is Jesus Christ and when stellar intellect is used to exalt and explain godliness to us, we praise and thank the Lord for men such as Dawson.

Colossians 3:2 Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth.

1 Corinthians 2:16 “For who has understood the mind of the Lord so as to instruct him?” But we have the mind of Christ.

Romans 12:2 Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.

2 Corinthians 5:17 Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come.

Philippians 4:8 Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is honourable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things.