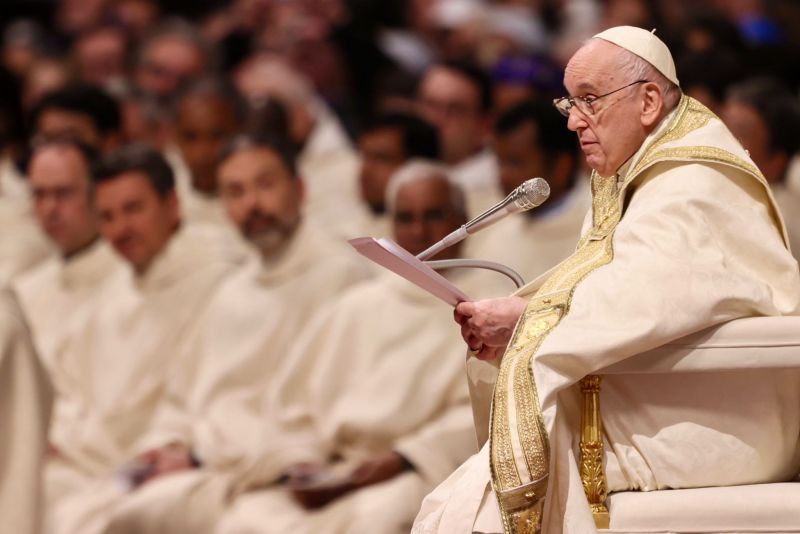

On June 19, 2023, Pope Francis marked the four hundredth anniversary of the birth of Blaise Pascal, the French mathematician and philosopher who remains one of the most important thinkers in the Western tradition. In his apostolic letter Sublimitas et Miseria Hominis (The Grandeur and Misery of Man), the Holy Father praises Pascal as a “tireless seeker of truth.”

The Pope rehearses some of the most important contributions from the seventeenth-century French thinker. The Holy Father, who trained and worked as a chemist as a young man, describes Pascal’s scientific prowess, including inventing a proto-computer. But he also highlights Pascal’s concern for the limits of human reason, pointing us to the famous “night of fire,” a mystical encounter where Pascal’s heart was moved to understand more fully the truth of Christ’s revelation. For Pascal, God was not a theory, but reality itself, and Pope Francis demonstrates his sympathy with this view by quoting from Pascal’s Pensées (Thoughts), “This is not the abstract God or the cosmic God, no. This is the God of a person, of a call, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the God who is certitude, who is sentiment, who is joy.”

Pope Francis also briefly describes Pascal’s relationship with the Jansenists, while somewhat downplaying it, I must admit. The Jansenists were a rigorous group who espoused the theories of double predestination and total human depravity, both of which the Church rejects. The Holy Father reminds us, however, that although Pascal’s sympathy for this sect was a scandal, it also came from an understandable concern for a problem that may be even worse today than it was in the seventeenth century: Pelagianism, named after the fourth and fifth-century heretic Pelagius, who espoused the general idea that we can achieve salvation by our own efforts rather than as a gift of God’s grace.

For these and several other insights into Pascal, we should be grateful for the Holy Father’s letter. But, curiously, one thing the pontiff does not discuss is Pascal’s famous “wager.” And as the wager is perhaps the most famous and important takeaway from Pascal’s broad intellectual offerings, it is worth exploring in the context of this anniversary tribute. The initial light that Pope Francis has shined on Pascal in his letter, therefore, provides an opportunity to open the aperture wider and capture the significance of this major element in Pascal’s worldview. Today, as in the seventeenth century, the choice of faith vs. skepticism—of God vs. nothing (or anything)–stands before us. Reading Pascal can help us cope, and by God’s grace, act.

In simplified form, Pascal’s wager describes how a person ought to live as if God exists, since if God does not exist, the worst-case scenario will be a finite, material loss rather than the loss of his soul. On the surface, Pascal’s wager may come across as kill-joy religion, reinforcing his association with the puritanical Jansenists. After all, Jesus turned water into wine at the wedding feast at Cana in John 2, and he declared elsewhere, “I came that they may have life, and have it abundantly” (John 10:10). Being a Christian isn’t supposed to be a drag!

But digging a little deeper, taking the wager is not meant to rob a Christian of joy in this life, but rather “to incite to the search after God,” as Pascal explains in the Pensées. There is no neutrality in this life. If we do not choose to bet on the big promises of our God whose treasure chest of grace is bottomless, then our default bet will go to the biggest charlatan of all time. As Bob Dylan sings on his 1979 album Slow Train Coming, “Well, it may be the Devil or it may be the Lord, but you’re gonna have to serve somebody.”

Moreover, Pascal’s wager does not presume an unreasonable demand on human freedom now. He is not saying we must be miserable slaves to God on earth so that we can be happy in heaven. Rather, his wager is meant to provide a framework for fruitful decision-making for the sake of joy in this life too. After all, we must choose, over and over again, and our reason alone will not deliver us in the right place. In fact, if our strategy is to be “free” to choose entirely on our own, we are guaranteeing our misery.

Pascal writes, “You have two things to lose: the true and the good; and two things to stake: your reason and your will, your knowledge and your happiness; and your nature has two things to avoid: error and wretchedness.”

Accordingly, the payoff for trusting in God’s revelation does not come only after we die.

Here it may be helpful to consider a couple of examples from basic moral decision-making. Drinking alcohol is permitted, for example, but we know when we’ve had too much. In our wretchedness, we may continue to overindulge; but as we mature, God willing, our own judgment may improve based on what we have experienced, and drinking up to a limit and no more becomes a joy instead of a chore. Sex is permitted too, and when we have sex only according its purposes as revealed to the Church, we are not only spared the soul-destroying misery present in any manner of sexual deviations–broken relationships, sexually-transmitted diseases, etc….–but we are blessed with the stability of a wife or husband to care for us “in sickness and in health.” In our old age, we may even be “free” to receive the loving care of children and grandchildren rather than be forced to accept the prison-like conditions of an old-folks home.

My favorite French filmmaker, Eric Rohmer, explores the question of Pascal’s wager in at least two of his films: My Night at Maud’s (1969) and A Tale of Winter (1992). I share here an extract from a piece I wrote about Maud in the print-only Evangelization & Culture journal last year:

Rejecting the Puritan tendencies of secularism, Marxism, and certain versions of Christianity, Jean-Louis [the film’s protagonist] holds up the example of food and drink, wondering what Pascal would have thought of an earlier vintage of the same local wine they are enjoying. Vidal [Jean-Louis’ Marxist friend] notes that Pascal never said about anything, “This is good,” prompting Jean-Louis to slap the table, point to his glass and say, “That’s it! Me, I say, ‘this, this is good!’” To Jean-Louis, Christianity ought to be the experience of an abundant reality, not an insurance policy against hellfire.

But then, Jean-Louis is presented with a real test of Maud’s objection to his piety. What are the limits of freedom for a Christian? Where does enjoyment of the gifts of God’s creation stop and indulgence in deadly sin begin? Vidal departs, leaving Jean-Louis and Maud alone for a long, tense scene in which the viewer wonders whether chastity or debauchery will win out. Jean-Louis’ moral resolve appears to fail just as Maud grows tired of the game, and the frigid night gives way to warm sun coming through the windows. In the darkness, Jean-Louis has explored the moral landscape right up to its furthest limit, and until the last minute, but without transgressing. A reader of the Bible may recall the Psalmist’s declaration, “joy comes with the morning” (Psalm 30:5).

Jean-Louis approaches Françoise the next day, and the new couple experience their own wintry night, stranded indoors together. But whereas intellectual debate and sexual tension dominated Jean-Louis’ night with Maud, pleasant theological badinage between fellow believers, as well as the total presumption of chastity, characterize his night with Françoise. The next morning, the two attend Mass together, and the priest says in his homily that Christianity is not mere morality, “but life.” Just as Jean-Louis has foreseen, the couple marry, beginning the next phase of a wholesome, joyous life with God together after confessing to each other the sins of their past.

Despite Jean-Louis’ explicit rejection of Pascal’s austerity, in a certain sense he nonetheless participates in Pascal’s wager. Leszek Kolakowski notes that “Pascal appeals to a kind of practical reasoning in order to compel the libertine to admit that he cannot avoid the choice between religion and irreligion.” Both Jean-Louis and Maud are, or were, libertines; but he chooses religion, and she chooses irreligion. In the end, Rohmer makes clear who made the better decision.

Pascal writes, “I tell you that you will gain even in this life, and that at every step you take along the road you will see that your gain is so certain and your risk so negligible that in the end you will realize that you have wagered on something certain and infinite for which you have paid nothing.”

We take a risk, yes, that our creator knows better than we do. And why would we not? Peter Kreeft notes that Pascal’s philosophy, and particularly the wager idea, reminds us that too often in this world “more attention is paid to the journey and its troubles than to the outcome.” But our end point informs the steps we should take to get there. That’s the wager, which Kierkegaard would later rebrand “the leap of faith.”

Celebrating 400 years of Blaise Pascal’s brilliant intellect and sincere heart for God reminds us today to tend today to what ultimately matters.

Take the bet. And enjoy the Penseés.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Dear Andrew,

Finding the Light: Science and its Vision by Dr. James, A. Cannon, recently published posthumously, is another wonderful witness to Paschal’s relevance at his 400th anniversary.

I considered Pascal’s wager on my way out of Catholicism. I came to the conclusion that if God doesn’t exist / Catholicism is false and I waste my life away trying to live according to a religion that’s making me miserable, depressed, anxious and unable to deal well with the tangible realities of everyday life, my loss is going to be pretty darn infinite – literally no higher one is thinkable in that case! Same can, of course, be said if God exists and Catholicism is true. However, since I can see a good deal more evidence against this possibility than for it, the rational choice seemed to ve clear.

I am sorry to hear that, but thanks for letting me know. May God’s great love for all his creatures embrace you.

Well, good luck with that. It’s a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God.

The author writes, “taking the wager is not meant to rob a Christian of joy in this life, but rather to incite to the search after God.” He continues, “his wager is meant to provide a framework for fruitful decision-making for the sake of joy in this life too.” Well put.

JPMA argues, “my loss is going to be pretty darn infinite,” that is, if he passes on the benefits of a totally secular existence by maintaining a belief in God and Catholicism.

Well, no. First of all, that could not be an “infinite” choice (i.e., in his view of the matter) but purely a secular one (of the saeculum) and, hence, quite limited.

He claims it as “rational.” Yes. But it misses the author’s and Pascal’s insight about the limits of reason. Is there surety in well-ordered reason toward the end of discerning how the truth of things stands? Yes, to a point. Is there an absolute guarantee attached to it. I think not.

But another question JPMA’s statement raises: what was it about his experience of Catholicism that led to his being miserable, anxious, etc.? Is there some inherent fault(s) in the Catholic system, or is something else going on?

If there is something else going on for JPMA, then THAT may be the deciding factor for him.

I would just add that the door is always open for JPMA and anyone else

Good article. Does anyone else feel that Pascal’s wager comes off more like an insurance policy rather than a genuine response to the living God? Perhaps I’m misunderstanding Pascal’s argument.

Pascal’s Wager is not primarily intended for believing Christians, but is one of a number of rational arguments to help bring nonbelievers to a willingness to consider Christianity.

You mean rationalism but you don’t want to say it.

Philosophy joke: Pascal asked Spinoza what he would wager and Spinoza said “Everything”. Get it?

The wager isn’t about Christianity. It just came from the mouth of a Jansenist.

From the mouth of one of the greatest scientists in history: f1=f1=pa1=pa2 ~ D(Ei-Ef)-D(Qi-Qf)+D(Ei-Ef)=D(nft/V)=XPascal=0 ! As I tell my kids, this and Newton’s First Law is proof of Aquinas’ unmoved mover. Pascal didn’t intend his personal notebook to be published but we who believe that science is affirmation of the Almighty thank his sister for publishing ‘Pensees’ posthumously.

Try another angle in Pascal’s favour, see what happens.

Question: How many ladders would you have to climb to reach Heaven?

Answer: One long enough.

Conclusion 1. : Proof of God

Conclusion 2. : Proof of Aquinas

Conclusion 3. : Proof Debunking Pascal’s Wager

Conclusion 4. : Proof Pascal won’t be Apostolic.

The constant canonizing of mixing of religion and science going on in and around Pascal hobbles and contemns the correct investigations required from faith and reason. Pope Francis is adding to problems.

Separately, Pascal’s scientific method(s) as well as his philosophy are defective and over-played and this is not the way to go about unpacking the complexity.

Physics is beautiful, calculus is beautiful and all of God’s creation is rendered as wonderful poetry in the languge of sciene and math. Pascal has no philosophy, does not try to mix science with theology, he just had some randomn thoughts in a notebook that he never intended to be published. But for many of us who use science, math and engineering principles on a daily basis, “Pensees” is the recorod of an attempt of a great scientist to bridge, the seeming contraditions between STEM and revealed word (“Reson, custom and insperation”- Pensees 245). “For the truth is perverted only by the change of men (Technology)” – Pensees 623. I am so glad that the Pope as a trained scientist gets it.

‘ It is necessary then, for a proper understanding of Pascal’s thinking on Christianity, to be attentive to his philosophy. ‘

https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_letters/documents/20230619-sublimitas-et-miseria-hominis.html

Pope Francis’ letter is structured in such wise as to set down that Pascal can’t be a danger back into Jansenism, Pelagianism and rationalism. Also Pope Francis assumes implicitly that Pascal understood Pelagianism at all or rightly -from which Pascal was at pains to distinguish his own work and separate the two. Pope Francis gets into a confusion adding that it is not necessary to reopen debate about Molinism in order to uphold Pascal and have him as a trusted guide for reasoning. And that Pascal mustn’t be seen as Jansenist even though his unresolved standing remains a scandal.

Very strange business!

‘ Pascal’s philosophy, ever paradoxical, is grounded in an approach as simple as it is lucid: it seeks to attain to “reality illumined by reason”.

…..

We should realize, however, that, just as Saint Augustine sought in the fifth century to combat the Pelagians, who claimed that man can, by his own powers and without God’s grace, do good and be saved, so Pascal, for his part, sincerely believed that he was battling an implicit pelagianism or semipelagianism in the teachings of the “Molinist” Jesuits, named after the theologian Luis de Molina, who had died in 1600 but was still quite influential in the middle of the seventeenth century. Let us credit Pascal with the candour and sincerity of his intentions.

This Letter is no place to reopen the question. Even so, what Pascal rightly warned against remains a source of concern for our own age: a “neo-pelagianism” that would make everything depend on “human effort channelled by ecclesial rules and structures” and can be recognized by the fact that it “intoxicates us with the presumption of a salvation earned through our own efforts”. It should also be pointed out that Pascal’s final position on grace, and in particular the fact that God “desires everyone to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth”, was set out in perfectly Catholic terms at the end of his life. ‘

https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_letters/documents/20230619-sublimitas-et-miseria-hominis.html

Thank you Mr. Galy, very informative. I have little familiarity of Pelagianism but will research more about it to put ‘Pensees’ in a better theological context. Also, don’t get me wrong, I am not a big fan of our Pope or Jesuits in general but am a big fan of St. Augustine, our local parish priest and of the mighty BH BB5 DDHFM hydraulic pump – possible because of the other writings of Pascal.

Justa Tourista, I would like to say, what (little) I have is from the Church and I am glad that you should see it.

Somewhere after 2014 WIKIPEDIA changed its original article on Pelaginaism that had insights from Jerome; to what is there now, not so clear anymore.

I am fond of saying that it was -is- Jerome who was the undoing pf Pelagius. It was not Augustine (all due love and honour).