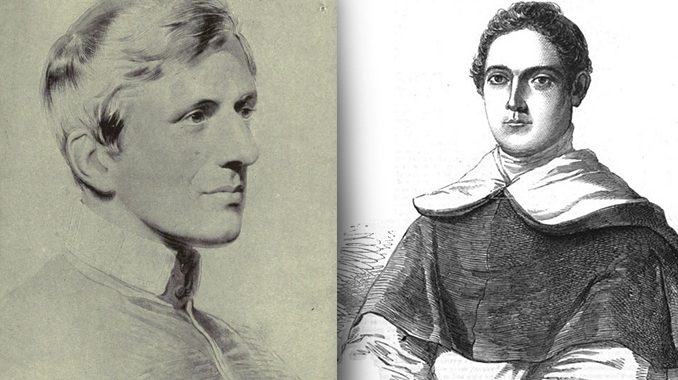

The Achilli Trial, as it came to be known, grew out of a lecture that John Henry Newman gave in Birmingham in 1851 entitled “The Present Position of Catholics in England”, only six years after his conversion, in which he referred to the sexual offenses of a former Dominican friar named Giovanni Giacinto Achilli (c. 1803–c. 1860), who made a lifelong habit of seducing and raping women on a truly Olympian scale.

A zealous convert to evangelical Protestantism after he was shown the door by the Dominicans, Achilli was a regular speaker on the anti-Catholic lecture circuit. In the impresarios of this circuit, William Francis Finlason, the barrister of the Middle Temple who was one of the trial’s reporters, saw a certain inveterate consistency. “They have eagerly laid hold of any instrument to assail that Church which is the object of their insane hatred; and of any agency to inflame their animosity against Catholicism… And in this frantic eagerness they have been utterly indifferent to the antecedents of their tools. They have stopped not to inquire, and even if they have heard cared not to reflect, but have recklessly employed any apostate who would assist them in their fell purpose of pandering to the fierce passions of a people perfectly possessed by the spirit of prejudice, against the Church which founded their Constitution and their Crown.”

Indeed, in the wake of the reconstitution of the English hierarchy in 1850, known as the period of ‘papal aggression,’ Achilli was taken up by the powerful Evangelical Alliance and gleefully exhibited as an eyewitness to the sins of popery. He even published an account of the grief he suffered at the hands of his former co-religionists, Dealings with the Inquisition, or Papal Rome, her priests, and her Jesuits, with important disclosures (1851), which one English reviewer could not have praised more highly:

Among the many volumes which the recent Roman Catholic movement has called into existence, this work of Dr. Achilli’s is likely to obtain the most permanent popularity. As an able and lucid digest against Popery, as a graphic description of many of the practices of the Romish Church, and as the record of the experience of a vigorous and enlightened mind, the work is one of the most valuable which the subject has called forth. There is in the generalities of our author’s account a truthfulness, knowledge, and mastery of the subject, and opportunity of observation, which will go far to make his volume a standard work in defence of the principles of Protestantism.

What is striking about Achilli’s confessions is how revelatory they are of his thoroughgoing apostasy: “While holding the head professorship of theology at Viterbo, and teaching with great zeal the Romish doctrine… I was no longer a Papist, for I had long ceased to believe in many doctrines which are matters of faith in the Romish Church.” Although a patent rapscallion, Achilli did occasionally contrive to tell the truth. “I had ceased to believe in the Mass,” he wrote. “I was like Luther and many others, who no longer believed the Mass, and still continued to celebrate it.” Finlason’s response to this admission is worth quoting:

“Like Luther”? The parallel will be perceived in many points, and was recognized by the patrons of Achilli, in and out of the Court of Queen’s Bench… It is curious to observe the moral blindness of the man. “I continued to celebrate mass with the show of devotion. I was perfectly persuaded of its imposture.” Then soon after he says: “To me friars and priests savoured of imposture: and the more I advanced in spiritual light, the more I felt myself adverse to such hypocrisy.” Spiritual light! “Why do you seldom attend choir?” asked one of the friars one day. “The rumour got abroad that I allowed everybody to eat meat.” “A confession of sins makes one melancholy. Confession had at length become so odious to me, that I could no longer bear it myself, nor endure the practice of it in others. My understanding began to be illuminated about that time; I began to be aware that we are not saved by our own merits, but by the merits of Christ, and that these merits are not imputed to us by the efficacy of the sacraments, but the virtue of faith.” That is to say, the “spiritual light” he rejoiced in arose at the time he abandoned the sacraments, and disbelieved in the adorable sacrifice.

In his entry on Achilli in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, the sprightly historian Sheridan Gilley argues that it is doubtful whether the serial rapist was a hypocrite. For Dr. Gilley, “…given [Achilli’s] insistence to his colleagues and his victims that he was doing nothing wrong, and his scornful refusal at times to answer charges against him, he possibly became an enthusiast of the Calvinist antinomian type satirized by James Hogg in The Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824), whose religious assurance carries him straight into disregard for the moral law.” Seen in this light, Giovanni Giacinto Achilli might be a useful cautionary tale for our own antinomians.

A passage from Hogg’s book makes Dr. Gilley’s point. A lady who suspects her husband of adultery tells the hero, Robert Wringhim: “I am scandalized at such intimacies going on under my nose. The sufferance of it is a great and crying evil.” Wringhim disagrees. “Evil, madam, may be either operative, or passive. …To the wicked, all things are wicked; but to the just, all things are just and right.” To which the lady responds with mordant irony: “Ah that is a sweet and comfortable saying, Mr. Wringhim! How delightful to think that a justified person can do no wrong!” Hogg, a Scottish shepherd’s son, may not have had much in the way of education beyond his reading of Robert Burns and Walter Scott but he was shrewd enough to see that “Religion is a sublime and glorious thing, the bond of society on earth, and the connector of humanity with the Divine nature; but there is nothing so dangerous to man as the wresting of its principles, or forcing them beyond their due bounds: this is above all others the readiest way to destruction.”

It was after Newman referred to Achilli’s “extraordinary depravity,” which made him “the scandal of Catholicism,” that the defrocked Dominican brought his libel suit. Avid to make the suit as damaging as possible, Achilli brought it as a criminal, rather than a civil action both because it would entail the very real threat of imprisonment for the accused and because it would bar Newman from giving evidence on oath at the trial. Whatever his objections to Rome, Achilli clearly recognized the inadvisability of giving so eloquent a defendant any courtroom pulpit.

On October 27, 1851, Newman was duly served with a writ charging that he had acted maliciously by publishing words that subjected Achilli to “great contempt, scandal, infamy and contempt.” In addition, the writ stated that Newman’s “false, scandalous, malicious, and defamatory libel” was “in contempt of our said Lady the Queen, to the evil and pernicious example of all others in the case of offending and against the peace of our said Lady the Queen, her crown and dignity.” In response, Newman entered pleas stating that his references to Achilli in his lectures were true and that he published them not out of malice but solicitude for the public benefit — a sensible solicitude in light of the fact that, in 1840, when Achilli was prior of the convent of San Pietro Martyro in Naples, a fifteen year old girl, Sophia Maria Principe had accused him of raping her in the sacristy on Good Friday. Newman also pled that “Achilli [was] not deserving of credit or consideration, by reason of his previous misconduct; and … preach[ed] and lectur[ed] to excite discord and animosity towards [the Roman Catholic Church].”

Newman had no illusions about the difficulties of his legal position. “Badeley [one of his most trusted legal advisors] tells me I have a work of extreme difficulty,” he wrote one correspondent; “but I rely on our Blessed Lady and St. Philip to carry me through. Indeed, it is not my cause, but the cause of the Catholic Church. Achilli is going about like a false spirit, telling lies, and since it is forced upon us, we must put him down, and not suffer him to triumph.”

Even before the trial began, Newman’s defense encountered the difficulties Badeley foresaw. First, Cardinal Wiseman mislay written evidence verifying Achilli’s sexual offenses, which obliged Newman to dispatch friends to Italy to collect the necessary evidence. Secondly, Wiseman failed to furnish a strong enough letter to the Neapolitan police to enlist their cooperation in gathering the evidence. Consequently, Newman and his allies had difficulty obtaining the necessary documents proving Achilli’s guilt. Lastly, some of the witnesses contacted by Newman’s agents refused to sign affidavits. In November of 1851, Newman wrote to one correspondent: “The series of strange occurrences connected with this matter it is impossible to convey to any one who is not with me. If the devil raised a physical whirlwind, rolled me up in sand, whirled me round, and then transported me some thousands of miles, it would not be more strange… I have been kept in ignorance and suspense…”

Nevertheless, the evidence compiled by Newman’s friends was compelling. One woman testified that she had had sexual relations with Achilli after he explained to her that it was no sin; another that he had raped and impregnated her; eighteen others swore affidavits that they had personal knowledge of Achilli’s sexual offenses. Even that quixotic Evangelical and factory reformer, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury (1801-85) testified that Achilli had been relieved of his duties at St. Julian’s College, Malta when his sexual misconduct came to light there.

Still, such abundant evidence was no match for the bias of the prosecution and the bench. Sir Frederick Thesiger, the lead prosecutor, told the jury when the trial opened at the Queen’s Bench that whatever affidavits Newman might produce would be dubious because, as he mischievously claimed, Catholic witnesses would naturally favor the word of an English convert over an Italian apostate. Another prosecuting attorney questioned whether the evidence produced by Newman from the Court of the Inquisition regarding Achilli’s offenses could be admitted in an English court, since England did not recognize the pope’s jurisdiction.

Newman’s lead counsel, Sir Alexander Cockburn was forced to spend most of the trial defending the integrity of the evidence, rather than its truth, though in his summation he touched on the one aspect of the case that made Newman’s conviction a foregone conclusion.

Gentlemen, I ask you to take these things into your calm and dispassionate consideration. I know the difficulty I encounter: I have felt it from the commencement. I have felt all along the disadvantageous ground upon which I am placed in defending Dr. Newman. We have here two great champions of opposing Churches — two converts from the faiths in which they were bred: both come forward, each to assert and maintain the truth of the Church he has joined; and I am pleading for one, a Catholic, before a Protestant tribunal. And the difficulty I feel must be, in such times as these, greatly enhanced. The spirit of proselytism, re-enkindled after a long sleep, has again arisen; and the Catholic, with upraised cross, and the Protestant with open bible, have entered into the arena to contend for domination over the interests of mankind. God prosper the truth, say I!

Thesiger, for his part, sought to convince the jury that Newman’s defense was tantamount to a Catholic conspiracy. In his account of the trial, “Roman Catholicism on Trial in Victorian England: The Libel Case of John Henry Newman and Dr. Achilli” (1996), the legal scholar M.C. Mirow underscores the ways in which this willful misrepresentation followed predictable lines:

Thesiger seized many opportunities to extract evidence of this highly believable explanation. Ample evidence was offered including the involvement of the Pope’s personal secretary, Monsignor Talbot to the English Catholic servant, Sarah Wood [one of Achilli’s accusers], who was observed not to eat meat on Wednesdays or Fridays. The jury was convinced that the Catholic Church could easily produce false documents… and compel the attendance of perjuring witness… by instructing … [them] that [their] testimony would be for the greater glory of God and the good of the Church.

In other words, the anti-Catholic prejudices of the English, equating the ancient faith with intrigue, superstition, pious fraud, and treason, and not the evidence, determined the case’s outcome.

And, here, it is important to note that it was the virulence of this prejudice that always informed Newman’s appreciation of what he was up against in trying to convert the Protestant English. In 1850, when indignant Anglican churchmen responded to Pope Pius IX’s reconstitution of the English hierarchy with petitions decrying resurgent popery, Newman wrote the mother of a former student and dear friend: “I don’t agree with you at being troubled at the present row. It is always well to know things as they are. …It has but brought out what all sober people knew, though one is apt to forget it – that the English people is not Catholicly minded. Many foreigners, many old Catholics, have thought they were – I dislike our smoothing over the nation’s aversion to our doctrines, just as I dislike smoothing over those doctrines themselves.”

Lord Campbell, the presiding Chief Justice, admitted the evidence from the papal court but with such prejudicial reluctance as to leave the jury in no doubt as to the weight he attached to it. Certainly, this pillar of the Establishment did not hesitate to call the jury’s attention to the fact that the sentence of the papal court against Achilli was theologically motivated and therefore dubious: “Dr. Achilli says it was for heresy, and that no charge of immorality was brought against him. It is for you to say whether you believe it was for heresy or for immorality.”

After being found guilty, Newman was fined a nominal ₤100. For the beleaguered defendant, the verdict constituted a moral victory—it was not a charge against him but against Roman Catholicism—and he pointedly instructed his counsel to reaffirm that he retracted nothing of what he had said against Achilli. The Morning Post published Lord Coleridge’s remarks once the verdict was made, in which the supercilious Justice addressed Newman directly, praising “the tenderness and gentleness of spirit” of his Anglican writings but urging “that if you again engage in this controversy, you should engage in it neither personally nor bitterly.” Newman’s response to this judicial impertinence, which he shared with Frederick Bowles (the former Tractarian with whom he had been received into the Church by Blessed Dominic Barberi) is worth quoting: “I had a most horrible jobation from Coleridge – the theme of which was ‘deterioration.’ I had been one of the brightest lights of Protestantism – he had delighted in my books – he had loved my meek spirit etc. etc.” To another correspondent Newman was even more candid:

I could not help being amused at poor Coleridge’s prose… I think he wished to impress me. I trust I behaved respectfully, but he must have seen that I was as perfectly unconcerned as if I had been in my own room. … [M]ere habit, as in the case of the skinned eels, would keep me from being annoyed. I have not been the butt of slander and scorn for 20 years for nothing.

What Coleridge failed to realize is that, in cases where attacks on the integrity of the Roman Catholic Church required refuting, the controversialist in Newman was never averse to taking off the gloves. Nevertheless, Coleridge was convinced that his scolding of Newman was justifiable, as he confided to his diary.

Perhaps I have been so much accustomed to hear Newman’s excellence talked of that I have conceived an exaggerated opinion of him. But I have a feeling that there was something almost out of place in my not merely pronouncing sentence on him, but in a way lecturing him. And yet as I could not avoid the one, so it seemed to me quite in course for me to do the other, when by breach of the law he had fairly been brought under me. Besides, in truth Newman is an over-praised man, he is made an idol of.

Despite Coleridge’s special pleading, the Times took Newman’s part, summing up the misconduct of the Queen’s Bench in memorably damning terms: “We consider … that a great blow has been given to the administration of justice in this country, and Roman Catholics will have henceforth only too good reason for asserting, that there is no justice for them in cases tending to arouse the Protestant feelings of judges and juries.” The novelist and clubman William Makepeace Thackeray, who followed Newman’s career closely, thought Achilli “a rascal hypocrite” but still considered the verdict just, despite the fact that “the Judge’s behavior in the trial was most unfair and unworthy.” Finlason claimed that the verdict exhibited England’s “blind and bitter prejudice against the Catholic Church,” though he consoled himself with the conviction that most Englishmen would not agree with it. “They will not sanction a perversion of justice,” he wrote, “in order to secure a triumph for Protestantism. They may not appreciate religious houses, but they venerate religion; they may reluctantly tolerate Popery, but they will not perpetuate iniquity.”

This may have been true but Achilli went scot-free and Newman was required to pay court costs of ₤12,000, a tidy sum in mid-nineteenth century England, which friends and benefactors from Great Britain, Ireland, France, Belgium, Germany, Poland, Italy, Malta, and North America graciously picked up. (Twelve thousand pounds in 1853 would have the purchasing power today of £1,478,550.31.)

Nevertheless, at this pivotal point in his life, when so many of his Catholic endeavors lay before him, Newman was transformed. No longer simply an English convert at the mercy of the Evangelical Alliance and its friends on the Queen’s Bench, he had become an English Catholic at home in a truly universal faith that stretched far beyond the pale of No Popery, and it was not only the flagrant injustice of the English legal establishment but the faithful largesse of fellow Catholics that helped him to realize the full meaning of this embattled profession. As he told another correspondent in the wake of the trial:

What is good, endures; what is evil, comes to nought. As time goes on, the memory will simply pass away from me of whatever has been done in the course of these proceedings, in hostility to me or in insult, whether on the part of those who invoked, or those who administered the law; but the intimate sense will never fade away, will possess me more and more, of that true and tender Providence which has always watched over me for good, and of the power of that religion which is not degenerate from its ancient glory, of zeal for God, and of compassion towards the oppressed.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

I thank Edward Short for his remarkable account of hypocrisy and blindness regarding the Newman case. Fr Achilli’s evil [a priest remains a priest forever even in Hell] is overshadowed by the immense evil of his prejudiced defenders more blind to truth that the miscreant they defended. I pray no one is eternally punished in Hell including Achilli and his Protestant defenders. Although hatred of Catholicism frequently shows the haters have no issue in being in league with the Devil.

If the offending Priests remain priests in Hell, then they at least need an asterisk beside their name. I was disgusted to see “pray for deceased Priests” column in a local parish bulletin listing one of the most vile sex abusers in the history of our diocese. I forgive the parishioner who placed the column since 95% of the parishioners are retirees who have relocated to the Parish and would not know this Priest’s history. Doesn’t the Gospel tell us the wealthy man was condemned to eternal Hell for ignoring the poverty of the Leper? What then awaits the Priest who used his position to rape? Six months and all is forgiven? One of our “beloved” clergy frequently rails against Luther and Lutherans but groveled at the feet of Joe Biden when given the opportunity. Do you see the hypocrisy in that? We did have a previous Bishop who refused to allow Joe Biden’s name to be added to a local Catholic School and said he would refuse him communion, though Biden skillfully avoided the situation. So is it then that the one who hate Catholics out of ignorance is worse than the Sex Abuser who after all was ordained and therefore eventually guaranteed Heaven.

How was the offending priest “guaranteed Heaven”?

Great piece! And all of Short’s Newman books are terrific reads.