While reading Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress I was comforted by the knowledge that I would be compensated for my opinion of it.

Here it is: Don’t bother.

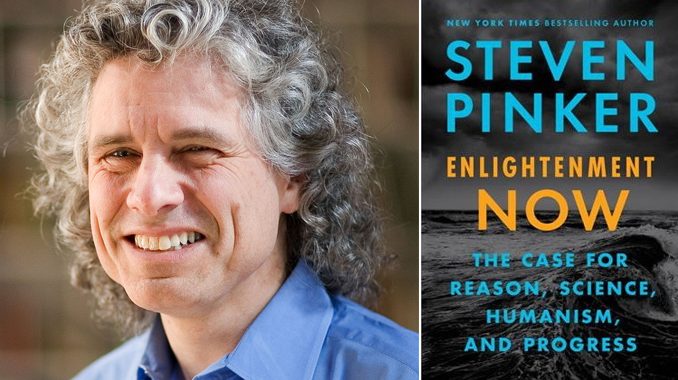

Enlightenment Now is the latest book by Pinker, a Harvard professor of psychology and prolific writer of pop academic books and articles. It is really two books for the price of one, but this is a burden, not a bargain. Together the first and third parts provide a slim (less than 150 pages) case for “Enlightenment ideals” and secular humanism—think of Christopher Hitchens without the style. Sandwiched between these sections are 300 pages extolling human progress. Pinker asserts that peace, prosperity, health, freedom and knowledge have increased, and he has the charts and graphs to prove it. Imagine reading an optimistic spreadsheet—forever.

Pinker’s goal is to show that Enlightenment ideals and humanism are the driving force behind human progress and flourishing. He claims that, unlike religion, the “Enlightenment has worked.” This connection between Enlightenment thought and human flourishing is the heart of his thesis. Without it the book is only a middling case for humanism wrapped around a stat dump on human material progress.

Consequently, a reader would expect a thorough historical account of how Enlightenment ideals led to the progress he recounts. However, despite having hundreds of pages in which to make his case, Pinker relies on assertion instead of rigorous historical analysis. He is content to work in the broadest possible terms, and he does not explore different strands of the Enlightenment. That he did not want to write a paean to Enlightenment thinkers is understandable; that he did not bother to demonstrate how their ideas led to the material wonders around us is inexcusable.

But even if the connection between Enlightenment thought and human progress is assumed, he must also show that the form of progress he describes has led to true human well-bring. The core of his argument is eudaimonistic—the Enlightenment is vindicated because it has promoted human flourishing. But although our increased wealth and scientific mastery are indisputable, Pinker struggles when it comes to the data on happiness, which has not increased as much as he seems to have expected.

He begins by scolding us, declaring that “If we have a shred of cosmic gratitude, we ought to be [happier]” and that “none of us are as happy as we ought to be, given how amazing our world has become.” Americans in particular “punch below their wealth in happiness.” This begs the question, as it assumes that prosperity produces happiness. But to the extent that happiness can be measured by surveys, the data suggest that there is something in the moral wisdom of the ages, which avers that the happiness that wealth can bring is limited and subject to diminishing returns. Prosperity and technology seem better at reducing physical sources of misery than at producing positive happiness.

Pinker seems to recognize the insufficiency of scolding people for ingratitude (and to whom, one wonders, does he believe they are ungrateful?). So at times he spins frantically to show that happiness is increasing. For example, he argues that a rising suicide rate is not so bad because past peaks have been higher than the current one. Elsewhere he asserts without evidence that if social media makes us unhappy, it is because “Social media users care too much, not too little, about other people.” This is outlandish to anyone who has looked at Twitter lately, but it illuminates Pinker’s ultimate diagnosis of modern unhappiness, which is that it results from increased wisdom and empathy.

Pinker recognizes that the good life is more than safety and prosperity, and that we also seek a sense of meaning that is often in conflict with the happiness provided by creature comforts. Meaningful activity often requires struggle, and caring induces worry. Thus, he suggests that “a modicum of anxiety may be the price we pay for the uncertainty of freedom.” He argues that enlightened moderns must confront the mysteries of existence and the responsibilities of the world without the comforts of traditional religion and authority. And so, “Though people today are happier, they are not as happy as one might expect, perhaps because they have an adult’s appreciation of life, with all its worry and all its excitement.” This is unconvincing and contradictory—are today’s citizens really more mature than their grandparents? Do they have more reason to worry than their ancestors who, according to Pinker, faced far more poverty, disease and danger?—but revealing. Pinker reaches for a flattering, but unproven and unlikely, explanation when the data do not go his way.

Fortunately, the tension between comfort and purpose has been explored by better minds than Pinker’s. Dostoyevsky gave us the image of the Grand Inquisitor—great, terrible and tortured as he defiantly seeks to “correct” Christ’s work and provide for the happiness of mankind. The masses will be happy: “we shall set them to work, but in their leisure hours we shall make their life like a child’s game…we shall allow them even sin, they are weak and helpless, and they will love us like children because we allow them to sin.” Only the rulers, such as the Grand Inquisitor, will be unhappy as they bear the burdens of humanity.

Life increasingly resembles the indulgent, comfortable world envisioned by the Grand Inquisitor, though we are bereft of the authority and mystery provided in Dostoyevsky’s tale. But this is no obstacle for Pinker, who is a sort of Bland Inquisitor. He instructs us to enjoy material comforts while finding our own meaning in life (provided it does not conflict with Enlightenment ideals—none of that traditional religion).

Perhaps Pinker’s sanguine faith in enlightened humanism will prove correct, but he has failed to join the two halves of his thesis. He does not prove that the Enlightenment was essential to the material prosperity and technological advances that surround us, and he struggles to show that Enlightenment ideals have provided for genuine human flourishing.

Consequently, the two portions of Enlightenment Now are left floundering, though the case for progress is stouter, as even thoroughgoing critics of modernity acknowledge the wealth and technological wonders of our age. But Pinker’s account of progress still has weaknesses. Some of the trends he praises, such as increased literacy in parts of Europe, started well before the Enlightenment, others well after. He selects some convenient starting points and data sets, and sometimes there is not much data to go on. Some statements are simply ridiculous, such as his claim that the “Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment set in motion the process of using knowledge to improve the human condition.” This dishonest conflation of two separate intellectual currents is historically false, though it suits Pinker’s narrative to pretend that rational thought began in 1753 (or thereabouts).

Throughout the book he misinterprets and misrepresents figures ranging from Burke to Hitler, and retcons anything he likes into the Enlightenment, and anything he dislikes out of it (i.e. attempts at the rationalization of society that failed horribly, such as communism). His historical and philosophical narratives tend to have more narrative than history or philosophy.

Furthermore, Pinker punts on a subject that must be confronted: abortion. He claims it as a virtue of quantitative methods that they treat each life as equal to others, but he does not factor abortion rates into his calculations. His ambiguity on the subject (he notes that abortion is controversial, and then hurries on) reveals intellectual cowardice; he is either afraid to defend abortion’s place in his progressive project, or afraid to put it into question. If developing human beings in utero have moral value, then his narratives of decreasing violence, increased human rights and longer lifespans fall apart before a ghastly medicalized murder machine.

This unwillingness to address difficult problems also hobbles Pinker’s case for Enlightenment ideals and humanism. Pinker confidently appeals to reason, but like the Enlightenment itself, he fails to provide an adequate definition of what reason is, or to adjudicate between the different and incompatible theories of reason suggested by various philosophers.

This is representative of a general failure to address the challenges posed to his views by opposing philosophers and intellectual traditions. For example, he mentions Thomas Kuhn’s classic The Structure of Scientific Revolutions in a single paragraph, and does not address its substance. He is content to abuse philosophers like Heidegger and Foucault in passing, even though he has hundreds of pages available to dissect their ideas in detail.

In the rare instances when he addresses a philosopher directly, the superficiality of his knowledge is revealed. He spends a few pages criticizing Nietzsche, but it is clear that he has probably not read him (his use of the usual out-of-context quotations is a giveaway), and has certainly not understood him if he has. Ironically, many of his attacks on Nietzsche are almost indistinguishable from those made by the religious fundamentalists he despises. He even has an absurd fantasy of confronting Nietzsche with violent threats to prove a point—as if Nietzsche wouldn’t see right through him, laugh, and compose a devastating aphorism in reply.

Pinker is also loath to engage with arguments made by serious Christian theologians and philosophers (such as David Bentley Hart’s takedown of Daniel Dennett), or even with intelligent popular apologists like C. S. Lewis and G. K. Chesterton. He prefers to target fundamentalists and the squishy spirituality expounded by the likes of Oprah.

Reading Pinker on religion is like reading the average angry internet atheist with a penchant for theodicy, with the addition of a copy editor and graduate assistants. He seems to think himself clever for comparing belief in the doctrine of the Trinity to belief in the Pizzagate conspiracy. A representative sample of his style is the assertion that, “To take something on faith means to believe it without good reason, so by definition a faith in the existence of supernatural entities clashes with reason.”

He nonetheless has faiths of his own. For instance, he would rather believe in multiverse theory (which must be taken on faith) than God. And throughout the book, his prejudices, which are almost a caricature of technocratic liberalism, are on full display. Conservatives may enjoy his digs at social justice warriors, communists and environmental doomsayers (his policy prescriptions will warm the hearts of nuclear energy lobbyists). Leftists will applaud his hatred of Donald Trump and other populists and nationalists, and many will delight in his attacks on traditional religious beliefs. But in either case, many of his assertions are rooted not in evidence, but the prejudices of his class.

These prejudices frequently lead him into a cascade of unsupported opinion and even misinformation. For example, he writes that “to this day it is unclear whether the Orlando nightclub massacre was committed out of homophobia, sympathy for ISIS, or the drive for posthumous notoriety that motivates most rampage shooters.” Apparently the murderer’s pledge of loyalty to ISIS is insufficient evidence for Pinker to determine his motivation. In another obvious bit of misinformation, he credits Trump’s campaign promise to repeal the Johnson Amendment for a “large part” of Trump’s evangelical support. In reality, most evangelicals have no idea what that is, and the ones who do had many other reasons for voting as they did.

These errors would be more excusable if Pinker were not so smug and humorless throughout this book. He tries to rely on borrowed wit to liven the slog, with his own contributions rarely rising above juvenile sarcasm (e.g. “ever-merciful God”). It does not help much. This is not a serious intellectual work; it is a mediocre entry in the genre of pop academic books. It is the atheistic equivalent of a prosperity gospel televangelist and it is unlikely to convince any informed person who was not already in agreement with Pinker. He is most successful in demonstrating that we are richer and more technologically advanced than we used to be, but that is not in much dispute. His attempts at historical, philosophical and theological arguments betray his ignorance of their substance.

However, Pinker is not out of his depth in Enlightenment Now, as he is perfectly suited to the intellectual shallows, with occasional commentary on what he sees on the surface of the depths he dare not explore.

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress

by Steven Pinker

Viking, 2018

576 pages

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

In his book “The Whys of a Philosophical Scrivener”, Martin Gardner wrote “About two-thirds of the face of Marx is beard, a vast solemn woolly uneventful beard that must have made all normal exercise impossible.” I wonder if anyone would take Steven Pinker seriously if he were bald.

A classic review!

From a more mathy viewpoint, Pinker’s problem is that he doesn’t understand the proper use of statistics. His assessments of progress are based on means instead of medians. The mean makes it sound like everyone is gaining when only the wealthiest are gaining. Medians and quintile-type measures give a much more accurate picture.

He also misses the basic nature of human perception. We don’t know or care about things that happened 1000 years ago, or conditions halfway around the world. We judge well-being compared to last year, and compared to conditions in our city. Most of us are worse off than last year and worse off than the Pinker types that we see around us.

What a great review!

Nothing in it surprised me about Pinker. He is just another example of the shallowness of those who parade their scientific knowledge as philosophy. They are oblivious of the great contributions made to all fields of knowledge, from the glory that was Greece to the achievements of catholic thinkers of all types from ancient through medieval times and continuing even today. That really is shallowness.

Even worse, modern scientists are poor historians even in the field of the history of science and its debt to Christian civilisation, as that great writer and researcher Fr. Stanley Jaki demonstrated in his immense life’s labours.

How strange it is that the shallow views gain so much traction today! Our reviewer had an easy target but it is essential that we persist with him in our struggle for the truth.