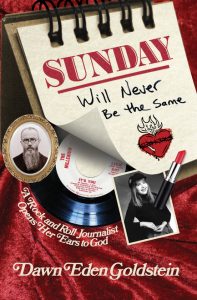

Dawn Eden Goldstein’s latest book, Sunday Will Never Be the Same: A Rock and Roll Journalist Opens Her Ears to God (Catholic Answers, 2019), chronicles her spiritual journey from a Jewish upbringing to Protestantism, and then to the Catholic Church, where she found healing and happiness. In 2016, she was the first woman to earn a doctorate in sacred theology from the University of St. Mary of the Lake, and is currently an assistant professor of dogmatic theology for Holy Apostles College and Seminary.

I recently spoke with Goldstein about her new book and her journey into the Catholic Church.

CWR: Congratulations on the publication of your memoir, Sunday Will Never Be the Same: A Rock and Roll Journalist Opens Her Ears to God. Not only is it an inspiring account of your spiritual journey, I think it also has considerable literary merit. What made you want to write it?

Goldstein: Ever since 2004, when the American Chesterton Society’s Gilbert magazine ran an article on my conversion from Judaism to Protestant Christianity—before I was even Catholic—people have been asking me to write a memoir. But I resisted because I thought a memoir meant telling every detail of my life. That sounded like an enormous task, plus it would mean that, for as long as I lived, my entire past would belong to every curious reader.

Even apart from my desire not to dwell on my past sins, the idea that strangers would know my entire life story wasn’t appealing. There are some beautiful memories that I wish to keep between myself, my family and close friends, and God.

What changed my mind was a conversation with my friend Kevin Turley, a Catholic journalist. He wanted me to write a memoir, and when I balked, he explained to me that I was confusing memoir with autobiography. An autobiography does indeed claim to be comprehensive, but a memoir focuses only on a particular time or event in a person’s life.

Once Kevin explained that distinction, I became eager to write what I had really wanted to share all along. It’s the story of how divine grace worked throughout my life, from earliest childhood, to guide me so that in spite of a most tangled path, I might eventually find the capital-L Love and capital-B Beauty that I had wanted all along. And it is intimate, and it does involve telling many details of my life. But it’s also reverent to myself and to my readers in a way that I couldn’t have accomplished if I were striving to be comprehensive.

CWR: Did you have any literary models in mind when you set out to write your memoir?

Goldstein: One model that often came to mind as I wrote was Sally Read’s Night’s Bright Darkness, which was recommended to me by Kevin Turley.

Read is a poet and it shows in the astonishingly powerful quality of her writing about her spiritual life. What’s more, her background is in some ways similar to mine. I found it helpful to see how she had condensed long swaths of her past, capturing what was essential so that she might convey the mental and emotional trajectory by which she came to open her heart to God.

I also noticed that Read paused her narrative at various places to explain Catholic theology on each of the seven sacraments. Her explanations are beautiful, as is the rest of her book. But I made a conscious decision not to follow that aspect of her approach because, as a professor, I worried that readers would think I was lecturing at them.

So I decided that, rather than stacking layers of theological interpretation onto memories of my life—which I did do in earlier books—I would instead write in the voice of my interior self as it was at the particular times that the events of the memoir took place. That way, I could make my story more immediate to readers.

Because of that choice, the few stories in Sunday Will Never Be the Same that I have related in past books read much differently. Now I am telling them not as they seem to me after eight years of studies in philosophy and theology but rather as I experienced them at the moment they happened.

CWR: What about Saint Augustine as one of your models? Do you see this book as your own version of doing an honest self-inventory, as he did in his Confessions? I thought your book was spiritually refreshing because of its unusually honest exposure of your inner thoughts at various times in your life. I don’t know if we would want to describe Augustine’s Confessions as more “autobiography” than “memoir,” but in any case your book did remind me of that Augustinian spirit that allows the reader to see you being honest before God about yourself.

Goldstein: I’m so glad you found my memoir to have an Augustinian spirit. It’s all but impossible for a Catholic memoirist to not have Augustine in mind, and certainly I did think of him as I wrote.

The teachings of Augustine that most influence my personal life, and that are beneath the surface of my memoir, concern his theology of prayer and desire. Augustine teaches that God created me with a hole in my heart so that He might fill it. That understanding—and the way Augustine reflects upon it in writings such as his Confessions and his Epistle 130 on prayer—is a never-ending source of reflection for me.

CWR: In your book, you describe how on October 22, 1999, during an episode of “hypnopompic sleep paralysis,” you heard a voice saying: “Some things are not meant to be known. Some things are meant to be understood.” It reminded me of the key episode when Augustine hears a child’s voice:

As I was saying this and weeping in the bitter agony of my heart, suddenly I heard a voice from the nearby house chanting as if it might be a boy or girl (I know not which), saying and repeating over and over again, ‘Pick up and read, pick up and read.’ [‘Tolle, lege! Tolle, lege!’] At once my countenance changed, and I began to think intently whether there might be some sort of children’s game in which such a chant is used. But I could not remember having heard of one. I checked the flood of tears and stood up. I interpreted it solely as a divine command to me to open the book and read the first chapter I might find. [Augustine then reads Romans 13: 13–14, and] … a light of relief from all anxiety flooded into my heart. All the shadows of doubt were dispelled.[1]

Why were you so convinced that the voice you heard was saying something from the Bible? You talked to your stepfather Ron, and also asked your mother about it, which caused you to think about and discuss Romans Chapter 5 with them, which finally led you to say, “Mom, I have to believe in Jesus now!” Maybe the voice could have been you remembering a song lyric you heard once? What made you so insistently want to look up Romans 5:1 when you were talking to Ron? It seems almost random, like Augustine flipping open the Bible. Was it?

Goldstein: When I described that episode—all those events that really happened, and which I interpreted as God drawing me to faith in Christ—I knew there was a risk that readers would think I was forcing a theological interpretation upon experiences that had a natural source.

Just a couple of days ago, a reviewer wrote to me that my feeling of being frozen in bed and feeling watched echoed that of people who claim to have been abducted by aliens. And indeed, a skeptic could say that, like alien abductees, I’m processing subconscious imaginings or hallucinations as though they were evidence of real-world events.

Writing about what happened to me on that date in 1999 gave me an opportunity to re-experience every moment, asking myself—as I did at the time—what was really going on.

I don’t doubt that my experience of sleep paralysis had a natural cause. But I can’t doubt that God, who is Lord of nature, had a hand in what happened through it and after it.

The voice that I heard was a voice that led me to the faith that I had fruitlessly strived after for years. And why would Romans 5:1 come to my subconscious mind as a means of interpreting the voice?

Perhaps my subconscious had simply been storing that verse, which I had probably read at some point or other, until the right moment. I don’t know.

But the truth is that even if there was a completely natural explanation to what happened, God was working in all of it. Because when I woke up on October 23, I finally had the faith that I had longed for, and—this is so important—after suffering from the temptation to suicide for my entire adult life, I no longer wanted to even think about killing myself. And after suffering likewise from the temptation to self-harm, I had the strength to resist harming myself again.

I don’t believe that my experience on October 22, 1999, is going to convert anyone. But it converted me, and that’s what matters.

CWR: Wonderful! I also thought that the theme of “God speaking through other people” was symbolically encapsulated in this episode. Your hearing of the voice (which the book’s subtitle perhaps alludes to?), or rather the voice itself, seems to represent all the ways God showed love to you through other people in your life. (I guess the theological distinction would be: the way primary causality used secondary causality to communicate love to you throughout your life.) Then at the end of the book you have a spiritual epiphany in a Catholic church about how God loves through the love of other people all the time, including the love of Mary. Weren’t you also using music in the book as a parallel metaphor for how God speaks to us and shows us love through the voices of others?

Goldstein: That’s a great question. When writing Sunday Will Never Be the Same, I did not make a conscious connection between the experience that sparked my conversion to Christianity and the epiphany I had about how God has been loving me through other people. And I wish I could say I had the wisdom to intentionally use music as a parallel metaphor, but that wasn’t conscious either.

Just the same, I do think you’ve hit upon an important connection, especially with regard to how I treat my love of music in the book. In writing Sunday, when I relived certain experiences of going to concerts or listening to a friend play records for me or receiving a cassette tape in the mail from my long-distance boyfriend, I felt great nostalgia and love for those who brought such beautiful experiences to my life. They may not all have intended to bring me a taste of God’s love, but that love was in those musical encounters just the same.

CWR: Indeed! What music are you listening to these days? You have great taste in music, and it is fun to read in the book of your experiences with the NYC music scene. I think people are looking for music that unexpectedly speaks to them in deeply spiritual ways. Do you have any recommendations for readers of your book who love your taste in music?

Goldstein: One of the great joys that has come to me through writing Sunday Will Never Be the Same is rediscovering the music of Robyn Hitchcock. I was fond of his music since first hearing him around the time I started college. However, at a certain point I stopped following him because I was too much in love with him, as only a teenage girl can be. It was actually painful to listen to him because he was this unattainable, romantic, David Bowie-like genius man of mystery.

Four years ago, I got up my courage and went to a Hitchcock concert for the first time in decades to see if I could handle it—bringing a friend for support. Although he was still everything I remembered, I was relieved to discover that I could tolerate all that beauty better than I could back in the day. Afterwards I went back to my room in graduate housing at the University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary and didn’t cry myself to sleep. Victory!

Now, during the run-up to the publication of Sunday, I’ve finally started catching up with the music Hitchcock’s put out since I lost track of him. It’s amazing, like listening to him for the first time. There’s much more going on beneath the surface of his records, both musically and lyrically, than I realized when I was focused on the romantic fantasy of him that I’d built up.

One thing that particularly strikes me is how God-haunted he is. I have no idea if he’s a believer—some of his songs poke fun at a kind of fundamentalist caricature of Christian faith—but he clearly takes the Bible to reflection. Just listen to “The Abyss” or “Shimmering Distant Love.”

CWR: Will do, thank you. Do you ever use musical examples and analogies when you teach theology to your students?

Goldstein: Very rarely, as I don’t share many musical touchpoints with them. But occasionally I’ll break into song just to make them laugh.

CWR: When you break into song, what does your singing voice sound like? I need you to name a musical artist, someone whose voice is closest to your own… or at least who you aspire to sound like as best you can…

Goldstein: I’d love to sound like Judee Sill, but I sound more like Nico.

CWR: That’s great, I like both, especially Judee Sill! Thank you, Dawn, and I hope everybody reading this gets the chance to read your book. I couldn’t put it down. I thought it was so good. Thanks for answering my questions. Your story is so beautiful!

Endnotes:

[1] Confessions VIII. xii (29), trans. Henry Chadwick (Oxford University Press, 1991), 152–153. Cf. also James J. O’Donnell’s electronic edition of the Latin text.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

Dawn is an excellent writer, and I’m sure her memoir will touch the hearts of many. Let’s give thanks to God for revealing his love through Dawn in such a powerful way.

Thank you, Ms Goldstein, How good, fresh and real (not to mention wise) to meet “I AM” on our way and embrace HIM. In all the chaos and noise of the world, one by one we meet HIM. The ones who are running so hard and fast the other way are doing all sort of harmful things to themselves and others. Even within the Church some are lost but I can never forget HIM who simply came into my life and I fell on my knees. No one can ever take that joy away. They have no right to my joy no matter what title they may claim. HE IS.

This is a wonderful interview.

One at a time.

The late great Frank Zappa was once quoted as having said “Rock journalism is people who can’t write interviewing people who can’t talk for people who can’t read.”

I don’t know if he ever really said it, but it is funny.