I would like to recall a scene of almost two decades past. I was in my first year of doctoral work and was studying, at home on a bright Sunday afternoon. I found myself reflecting on all I had been learning about the political history of modern Europe and the making of modern literature and, conversely, the troubling ease with which it seemed one could dissolve a literary work into its political and historical context as if these alone were its cause and meaning.

What had I come here to study? I asked myself. I wanted to write poems. I had already written some. I was committed to, reverent before, I wanted to practice, the craft of poetry: its traditions and techniques, the rigor of a meter that brings measure and order to human speech, of rhyme with its alogical but striking reasons, and of every other aspect of the art comprehended under the name of form. In reading a poem, we readily see how elements such as these converge to make of what was separate a new whole—a new whole that, taking its place in the world, has an integrity all its own. We see also that we may enter that new thing as we might into the depths of a mystery we shall never quite exhaust.

I had come to school in order to study form—aesthetic form—the forms of poetry. What I wanted most to do, I thought, was to write about those modern poets who had practiced those forms best, to be their interpreter and advocate, and to try to join them in the doing. This had once seemed important, not because I simply delighted in form—though I did—but because the perceiving of aesthetic form seemed to disclose something about reality. Good form said something about goodness. Poetic truth had something to do with truth in general.

But what had I really been doing? I asked now. I wanted to study good poetry, sure, but what made a poem good? I read it as if it were a source of true wisdom, or at least, I had thought I did. I heard in the back of my mind, some Victorian voice lost in reverie and speaking of the immortal beauties of poetry. Sitting there in the sunlight, I thought, What makes the beauty of a poem? And then, “wait,” I interrupted myself, “what is beauty?” The question embarrassed me. If someone were to say that word in conversation, I thought, I would probably smile an indulgent smile and change the subject.

But is beauty something to be smiled at? I would like to argue that, indeed, it is, but not in the way I then presumed. Certainly not with the condescension that I could then feel only as a reason to blush. “Let us talk about politics, let us talk about the use of ideas, but please,” I thought, “let us not talk about ideas as if they were vessels of truth in themselves—or of beauty, which sounds more like a cover for our indulged sentiments than the name of a reality.”

Beauty . . .

There was something wrong here. I sensed that beauty was no old word to be sniffed at, but I could not think of why. Intelligence, in our day, after all, often wears the mask of disillusion, disenchantment—it had nothing to say about “beauty.”

It took me some time to figure out even how to begin thinking otherwise. When I finally did, it was under the name of being. Not too many of us study metaphysics in our school days, and I was soon made to see how deeply that hurts and hinders us. When we try to make claims about the meaning of the world, we generally do so in a tentative and insecure fashion, and do so, because we fear a discontinuity between the fullness of thought and the ostensible bareness of things. Our experience of the world may be rich, but our confidence in the reality of that experience is thin. The first great discovery I made in my studies was the deceptively simple claim that all our thoughts about things find foundation, stability, and rest only insofar as they can find expression in terms of being. Being is our word for everything that is real, and nothing is real except being.

My studies in literature had, until then, been hobbled by a failure to take this properly into account. Literature builds up imaginary worlds, ideal worlds sometimes, fictive worlds often, but its interest for us always derives from its relation to reality. And so, it became my new ambition to think metaphysically, to think in terms of being, knowing that only then could one see reality as it was. I turned to the old masters of the subject, Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas, and in them I discovered the language of essence and existence, and matter and form, and sensed that these terms would bring clarity where frustrated incredulity had ruled before. They showed me, as did two other thinkers, the poet-critic Yvor Winters and Pope Saint John Paul II, that knowledge of being was the only possible source of confidence in reason. Knowledge is not a contemptuous smile for the fancies of others, but an experience of the adequacy of one’s thought, one’s reason, to being as it really is.

And so, I began to look for the occasions when the being of art seemed to demand consideration of being in general, when art touched not merely on life as we imagine it but on that place of meeting between essence with existence. This issued first in a series of essays that considered what it means to speak of being as deep. If to be is, as Aquinas suggested, the act of existence and essence together, then just to be one thing entails not being reducible to one dimension. Being is always a whole greater than the sum of its parts; it is always more than itself. In the modern poets as well as in the medieval and ancient philosophers, I found a vision of reality that could contain multitudes. Reality is not just the denuded substratum of matter, but the being of things in their depths . . . this my authors told me.

Those poets in whom I had long been interested I soon saw for the first time—it was just this insight they were honoring. They were trying, in poem after poem, or in their work as a whole, to reveal the error of our unhappy tendency to reduce reality to raw stuff. In the work of the Irish poet Louis MacNeice, I found a man who liked Aristotle’s vision of the world but was afraid to embrace it, because he feared that life, after all, may be just an empty motion of limbs. In the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins and T.S. Eliot, of Winters and Helen Pinkerton, I found authors who were real authorities, that is, who wished to reveal our lives as an immersion in existence, as an encounter with being.

But what was in that depth? It was the language of “form” that would soon clarify the question for me. The twentieth-century philosopher and disciple of Aquinas, Jacques Maritain, sought to remind the world that to encounter being was to encounter a reality that can be known, and which can be known only because it has first been intelligibly formed. Form, as the ancients used that word, refers specifically to the intelligible essence of things. Many of you will remember your Plato: to know the truth is to gaze up at the intelligible forms that are the real source of every thing in its particular nature. If, therefore, form is partially constitutive of a thing, then that entails that truth is not just an idea in the mind, but a property woven into the fabric of reality. As the philosopher Louis Dupré once noted, this idea of form stands among the most ancient and odd claims of the classical world: the truth appears. When we know something—truly know it—we see it, we see its form. Thinking over what that entailed became my task. In fact, it’s still my task.

If you have ever read The Waste Land of T.S. Eliot, you likely noted a feature of that modernist poem likely to provoke the average person’s indignation. To its four-hundred thirty odd lines, the poet had appended six dense pages of endnotes. Those notes served to reveal that hidden within the fragmentary, often obscure lines of the poem were meanings of which we might otherwise remain unaware. But what, I wondered, did it mean for a reader to say that the kind of being that a poem is is one that means? In what sense could those footnotes pertain to the poem? We might think of these questions in reference to books more generally. If a copy of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice sits on my coffee table, where is its meaning then? When I open it, I find a novel about the making of a good marriage; when I close it, where does that plot go? If I pointed to the book and said, “This is the story of the Trojan War,” you would surely say that I am lying. And I would be. Maritain it was who gave me a way to speak about this. A thing is knowable only in terms of its form and being—a book, you will not be surprised to hear, is in the form of a book! But the meaning of the book exists within the book as what Maritain calls intentional being. It is, he tells us, intentional being that leaps into actuality as our eyes scan a page. It is intentional being, moreover, that passes through the hand of the painter and through the brush in order to bring into actuality not just a canvas with paint on it, but a portrait of a lady. Hopkins writes, in his poem “God’s Grandeur,” the following lines:

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs

What fascinated me was that to say there “lives the dearest freshness deep down things” extended to being in general and even to that particular kind of being that is a word. Hear, for instance, that last phrase: “the brown brink eastward, springs.” The morn of a new day, the dawn of a new hope, expressed together with the color “brown.” A rather neutral, inert, uninteresting word it would seem. But then we think morning and brown, and we find hidden inside this phrase another one, from Hamlet. After seeing the ghost of Hamlet’s father during the night watch, the good Horatio says,

But, look, the morn, in russet mantle clad,

Walks o’er the dew of yon high eastward hill

And we say, what a pretty turn of phrase! But, why should the morning walk over the eastern hills, in a russet—that is to say, in a brown—mantle? In the Gospel of Saint John we read the following about a more ancient dawning:

Mary was standing outside the tomb crying, and as she wept, she stooped and looked in. She saw two white-robed angels, one sitting at the head and the other at the foot of the place where the body of Jesus had been lying. “Dear woman, why are you crying?” the angels asked her.

“Because they have taken away my Lord,” she replied, “and I don’t know where they have put him.”

She turned to leave and saw someone standing there. It was Jesus, but she didn’t recognize him. “Dear woman, why are you crying?” Jesus asked her. “Who are you looking for?”

She thought he was the gardener. “Sir,” she said, “if you have taken him away, tell me where you have put him, and I will go and get him.”

“Mary!” Jesus said.

She turned to him and cried out, “Rabboni!” (John 20: 11-16)

In the first light of Sunday morning, as the eastern sky brightens, Mary Magdalene sees a stranger in humble dress, a brown mantle no doubt, and so she takes him for the gardener. She speaks to him and does not know him; he speaks, and she wakens, and sees that the Christ lies hidden within the appearance of a rustic.

And, this encounter of Mary with Christ in his russet mantle at the dawn of a new day, indeed a new age, lies hidden within Hamlet and its tragic interlude of reckoning between faith and nothingness; and Hamlet dwells within Hopkins’ sonnet, where despair is canceled by the depth of being and the superintending of the Holy Ghost. Things do not just exist, they do not just “be.” The morning is always more than that dawn. Things mean things. Intentional being lies stacked like print within the being of a book, waiting to be recognized. And so, to be is also to be true.

At the same time I was considering these matters, I was also reading the work of the contemporary moral philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre. Although he had little to say about being, he had much to say about a feature of it often obscured in our thinking. Moral-thinking, MacIntyre proposes, is impossible if we do not think in terms of the good to be attained. Ethics, as Aristotle first elaborated the field, entails inquiry after the nature of the good at which human life aims—and this good everyone calls happiness. We cannot properly know what is moral, if we do not first know the nature of happiness, of the good proper to ourselves, and think in terms of it.

MacIntyre’s insight was in itself tremendously important, but, I slowly came to see, it had also to be extended to being in general. We think of the full meaning of a work of literature as the good of the parts that makes its expression possible. As we look out at the world, we see that we do not really understand things unless we know about them in terms of their final cause: their why, their end, purpose, or good. Imagine trying to explain what a hammer is, for instance, without making reference to what it is for. But, follow me through a piece of logic: if to understand things is to know their good; and we demonstrably do understand things (or we could not even raise the question); then that entails that to know reality, to know being, means also to perceive good in being and being in terms of its goodness.

Reality is being, and being contains in its depths truth—indeed truth upon truth—and among those truths is the goodness of being in itself. I began to see that so much of what draws us to literature is just its capacity to see the ordered wholes of lives leading to—sometimes attaining, sometimes failing—their intended good or purpose. This explains why so many authors over the centuries have thought the telling of stories to be a mode not just of instruction about events, but of moral instruction about how events relate to one another to form a plot, and every plot concludes on a judgment in regard to some good. To know the truth, we have to know what things are good for. To know the truth about ourselves, we have to know what we are good for, and that entails knowing our story. To know our story is to see the form of our lives whole. So often we think of stories in terms of fiction, but that is not really a just association. Although we often tell fictions to ourselves, we arrive at self-knowledge just when we see the form of the true story of our lives for the first time, and judge its goodness. Fictional stories frequently help us to see the form of true stories.

Listen to that phrase—“we see the form of the true story of our lives for the first time.” It took me a very long time to perceive the deepest mystery there for what it was. To know is to see, to see form, I have already proposed. Form is constitutive of being; everywhere there is reality, there you will find form, and form is what we know. The way in which reality gives itself to us to be known, the way being gives itself to other being, is through its existent form. A being stands forth in and through its form and, because this is so, we may know a thing in itself and may see it in its manifold relations to other things, as a book relates to its meaning, Eliot’s poem to its notes, a son to his ghostly father, this day to the whole span of a life, a creature to the grandeur of God. When we understand these things, we know them in themselves and in their relations; and, when we perceive the whole, we apprehend something that may well have struck us with power and mystery long, long before.

When we encounter reality, I mean to say, we discover that being’s capacity to give itself to other being is a great mystery. It is the mystery, in fact, and it is what has always been comprehended—whether by the philosopher speaking or the awed person stunned by reality—under the name of beauty. The classical definitions of beauty speak of the splendor of truth, wherein truth is a form whose radiance gives itself to make things stand out in existence, to share themselves, and so, to be encountered by the soul of another. And so, we hear of beauty as the splendor of form, or just plain old, form and splendor. To see these things is to receive, to perceive, the form of things existing in themselves, and also to perceive their splendor, the harmonious attachment of the particular to the whole visible mystery of reality. The true mystery of the world is not that it should contain some beauty, but that beauty should be the cause of the world—is the gift, the gratuity, that lets the world to give itself in being; that stirs the mind to wonder and search for truth, and the person to pursue what is genuinely good.

Here at last was an explanation for what had been a mere experience before, but a powerful experience, for it had led me to read literature, to take delight in art, and to begin to write poetic forms. Beauty is that which discloses the being of things as formed. Reality is known by its forms. The work of art is a form that draws attention to itself so that we can see the form itself and beyond it or through it to the real-forms of truth in its splendor.

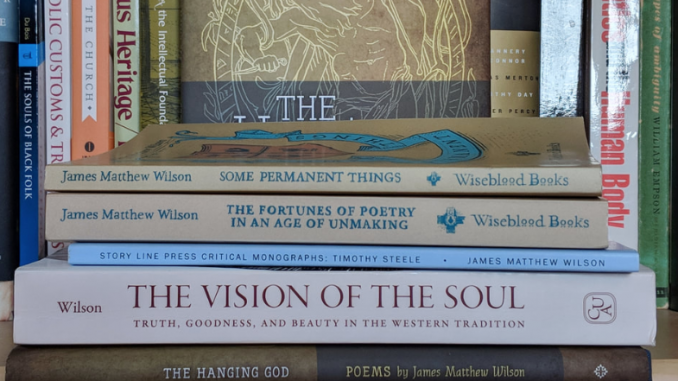

This is what I have learned and, in retrospect, it explains everything I was already trying but failing to do. Why I have spent these two decades hacking away at poems, trying to bring words into some permanent form, for their own sake and for what they can reveal to us about the nature of things. Some of those poems, you will note, are gathered under the title, Some Permanent Things. Why I have, sometimes a bit caustically, sought to defend the writing of good poems in the face of all those contemporary figures who would seek to dissever form from splendor, art from life, beauty from truth, intellect from being—who would have us think reality a mere poverty of atoms. Such was my labor in the book The Fortunes of Poetry in an Age of Unmaking. And this is why, at last, I sat down to write a book called The Vision of the Soul: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty in the Western Tradition. There, I tried to gather and to distill what I had had to search out and cobble together, often in solitude, over many years. I did this so that some future young scholar may not find himself at ease on a Sunday afternoon, delighting in the beauty of some bright page, only to startle himself with an incredulous blush of shame, thinking that beauty is a word only for those who do not know enough to reject it. To the contrary, it is the word for reality that keeps giving and giving and will not cease in giving. In the face of such a gift, what can we do but smile?

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.

My favorite line, there in the last paragraph: “Why I have, sometimes a bit caustically, sought to defend the writing of good poems in the face of all those contemporary figures who would seek to dissever form from splendor, art from life, beauty from truth, intellect from being—who would have us think reality a mere poverty of atoms”. That Dark Fracturing Separation War is Satan and his parasites’ favorite hobby. And, YES, sometimes we have to be “caustic”, just like Jesus was and is, when we stand up for AUTHENTIC TRUTH and BEAUTY.

Paragraph 19 (if I’m counting right): “Although we often tell fictions to ourselves, we arrive at self-knowledge just when we see the form of the true story of our lives for the first time, and judge its goodness”.

Paragraph 21: “When we encounter reality, I mean to say, we discover that being’s CAPACITY TO GIVE ITSELF TO OTHER BEING is a great mystery. It is the mystery, in fact, and it is what has always been comprehended—whether by the philosopher speaking or the awed person stunned by reality—under the name of BEAUTY” [capitals mine].

It all leads to Jesus Sacrifice on the Cross as Ultimate Absolute Beauty. All our lives, with their errors, sins and warts included, all poetry, all art, all social work, all spirituality, all science, all architecture, all sex in legitimate marriage, all our dreams, etc. must be allowed to be magnetized by the Infinitely Beautiful Holy Gravitational Pull of Jesus Cross: “And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, I will draw all people to myself”, (John 12:32). Surrender to HIS INFINITE BEAUTY not to blinding, dehumanizing, human sentimentalism!!

Many poets/searchers subvert the ways of the world with a handful of stories, and they could claim a share to these beautiful words by Francis Thompson “Turn but a stone, and start a wing! ‘Tis ye, ‘tis your estranged faces, that miss the many-splendoured thing”

So yes! As you say Phil, the pull of the Cross “draws us into His infinite beauty” as it exposes the reality of sin (Stones) within of our own hearts as the ‘recognition’ (Turning over) of them ‘deserve’ our honest attention, as it will lead us, in our frailty, to embrace Him on the Cross.

kevin your brother

In Christ

Thank you for providing an antidote to the feelings of profound discouragement that can overtake a person who makes the mistake, on a Sunday morning, of reading comments at The New York Times.