“If you find out, tell me.” That was Christine Choury’s exasperated response to one reporter’s now all-too-familiar question: Where is Bishop James Wingle?

“If you find out, tell me.” That was Christine Choury’s exasperated response to one reporter’s now all-too-familiar question: Where is Bishop James Wingle?

Choury, the director of communications for the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB), had no answer. Neither did anyone else.

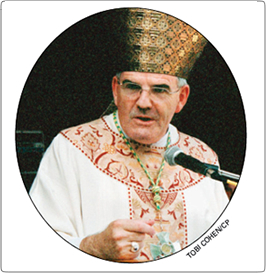

One day, the 63-year-old bishop of St. Catharines, Ontario was “handing out Easter candies to nuns, attending meetings and making plans,” as the Toronto Star put it. Then, three days after Easter Sunday 2010, Wingle surprised everyone when he faxed a letter of resignation to each of the 46 parishes in his diocese, addressed to priests and parishioners:

My decision to offer my resignation was the result of a long and intense process of prayer and reflection. The duties of the office of a diocesan bishop call for vigorous stamina to meet the challenges of leadership. I am no longer able to maintain the necessary stamina to fulfill properly my duties. I believe that my resignation will serve not only my own spiritual and personal well-being, but the good of the diocese and the Church as well…. If my shortcomings and limitations have caused any disappointment, I ask for God’s mercy and your understanding.

And with that, Wingle disappeared. He was, by all accounts, a keen traveler. However, this time he’d vanished to parts unknown, and left behind no telephone number or forwarding address.

Like so many contacted in the wake of this strange development, veteran Christian journalist Deborah Gyapong had nothing but good things to say about Bishop Wingle. Gyapong reports from the nation’s capital region, and is intimately familiar with the Canadian Catholic “scene.”

“Though I didn’t know him well,” she told CWR, “I always found him to be an extremely kind, fatherly, and loving bishop who not only upheld the Catholic faith with his words, he seemed to exemplify the faith by how he lived it.”

Typical was Wingle’s reaction in 2008 to the news that the country’s most notorious abortionist, Dr. Henry Mortgentaler, would be receiving the prestigious Order of Canada—comparable to the Congressional Medal of Freedom in the US—for his efforts on behalf of “women’s health.” The Bishop penned an eloquent condemnation of the honor, and called upon parishioners to contact their Members of Parliament to express their opposition. His letter still enjoys pride of place on the home page of the diocesan website. (As does a photo of a shy-looking Wingle, next to the words, “My dear friends in Christ, it is with great happiness that I welcome you….”)

Now, Wingle’s decades of service are being overshadowed by the mysterious circumstances of his resignation and departure. Sadly, it goes without saying that Bishop Wingle’s cited reasons for resigning—a lack of “necessary stamina”—didn’t convince everyone. With the Pope’s handling of the international sexual abuse crisis making fresh headlines this spring, cynical observers wondered if new accusations and charges were on the horizon.

Unfortunately, cynics have reason to be suspicious about members of the Canadian episcopate. Just a few months earlier, Bishop Raymond Lahey of Nova Scotia’s Antigonish diocese had also resigned suddenly. Shortly thereafter, news broke that he’d been arrested. Nearly 1,000 images that the police called “child pornography” had been discovered on Lahey’s personal laptop computer while he was being screened at the Ottawa airport.

What made the discovery and subsequent charges even more shocking was the fact that Lahey had recently been hailed as a victims’ champion for brokering an historic $15-million settlement for victims of sexual abuse by priests in his diocese.

Meanwhile, Bishop Wingle’s own diocese had also been rocked with a sexual abuse scandal. His resignation came only two weeks after a former priest named Donald Grecco pleaded guilty to abusing two altar boys in the 1970s and 80s. One of the victims had approached the St. Catharines diocese shortly after Wingle was appointed bishop in 2001. The other came forward four years later. Grecco was subsequently arrested, and he pleaded guilty and was scheduled to be sentenced on June 3.

In the wake of Bishop Wingle’s disappearance, the vicar general of the diocese, Msgr. Dominic Pizzacalla, told the Toronto Star that all the standard protocols were followed in the Grecco case. “There are procedures that we go through and the procedures were carried out,” he said.

Pizzacalla directed reporters to the diocesan website if they wished to review those protocols, but neither the Toronto Star reporter, nor CWR, were able to find them anywhere on the relatively simple site.

This air of secrecy and obfuscation (be it intentional or accidental) doesn’t inspire confidence.

EXASPERATION

One of Canada’s highest profile Catholic priests publicly expressed the exasperation that is privately shared by his fellow clergy. Rev. Thomas Rosica is the chief executive officer of Salt and Light, a Canadian cable channel that produces polished, original, orthodox Catholic programming. Among many other accomplishments, he helmed the successful World Youth Day event in Toronto in 2002, which included a visit from Pope John Paul II. For his efforts, Rosica received the papal “Pro Ecclesia et Ponifice” award the following year.

As one of the Canadian media’s “go to” Catholic priests, Rosica was asked for comment by the Toronto Star a month after Wingle’s resignation and departure. “He’s out of the country— that’s all we know,” Rosica said. “Where? God only knows…. It doesn’t smell right. When the [resignation] announcement came out, I had a number of bishops phoning me and [saying], ‘What the hell is going on?’ And I said, ‘You’re asking me?’”

Given the fact that the sexual abuse charges against Donald Grecco were again in the news, putting Wingle’s diocese back in the media spotlight, Rosica added, “The timing was unbelievable.” According to Rosica, Wingle’s temporary replacement has told him that he “finds it personally very frustrating that he doesn’t even have access to [Wingle]. I believe him, which even makes it more ridiculous.”

That replacement is Msgr. Wayne Kirkpatrick, who was elected administrator of the St. Catharines diocese by the six local priests who comprise the College of Consultors. Kirkpatrick is also the rector of the Cathedral of St. Catharine of Alexandria, the chancellor of the diocese, and judicial vicar. In his current post, he cannot carry out pontifical functions within the diocese. But he may still administer the sacrament of confirmation, and delegate other priests to do so. Kirkpatrick will remain as administrator until a new bishop is appointed.

“The administrator is not to do major innovations or changes,” Kirkpatrick assured Toronto’s Catholic Register. He added that Wingle’s resignation “came as a surprise to us all. People were really shocked.” Wingle’s decision to leave due to a lack of “stamina,” said Kirkpatrick, indicated that he “had the good of the diocese in mind.”

Kirkpatrick’s predecessor had “provided very good leadership,” and was a “very pastoral man” who “truly lived his faith.” However, Kirkpatrick added that he was also “a private man” who hadn’t shared any troubles he might have had.

Kirkpatrick was considerably more forthcoming with the Register than he was with the Star, whose reporters complained that they had emailed 17 questions “about Grecco, Wingle, and church protocols” and “Kirkpatrick answered none of them.”

All these recent events are especially troubling to Canadian Catholics, whose shame over revelations of abuse, which rocked the nation in the late 1980s, had been somewhat alleviated by the groundbreaking reports the Canadian Church authored in their wake.

In 1990, the Winter Commission investigated the infamous scandal surrounding the Mount Cashel orphanage in Newfoundland. In 1992, the Ad Hoc Committee on Child Sexual Abuse, established by the CCCB itself, made further recommendations for changes to Church policy.

Today, it is taken for granted that dioceses will employ a “zero tolerance” approach, and treat abuse accusations as criminal matters rather than “internal Church matters.” Priests are more likely to be charged by the police than simply fobbed off to another unsuspecting parish. Seminary screening procedures have changed to try to weed out potential abusers. These shifts in thinking came about as a direct result of those two 20-year-old commissions.

Not all these reports’ recommendations were greeted with enthusiasm, however. The Winter Commission insisted there was no connection between homosexuality and sexual abuse; rather, it was critical of mandatory priestly celibacy, which it claimed created “excessive and destructive pressures” on some individuals.

Others found the Ad Hoc Committee’s report, “From Pain to Hope,” too dependent upon the therapy-speak in vogue at the time, especially since it had been published by the CCCB itself. Such an informal imprimatur seemed to legitimize “consciousnessraising” “study sessions” that included “breathing, visualization, and roleplaying techniques.”

It sometimes seems like Canada’s Catholic leadership is ignoring their own famous findings on “best practices” for preventing, and dealing with, such scandals.

“The approach that I see is not in the tradition of brave action for justice that I’ve come to respect the Canadian bishops for,” remarked Sister Nuala Kenny. Kenny, a pediatrician and professor emeritus of bioethics at Dalhousie University in Halifax, sat on both the Winter Commission and the Ad Hoc Committee.

She recently told the Global Post: “I think it’s ‘Head down, if it didn’t happen here, if it’s not happening now, if we took care of that, let’s move on.’We’re not taking the opportunity for this larger conversation.”

“But that’s where the systemic issues kick in: If you’re (simply) trying to avoid scandal and you’re into denial about some of these things, they don’t go away,” she added.

Undoubtedly, the pressure of dealing with local priestly sexual abuse scandals must be considerable, leading many to speculate that Bishop Wingle simply couldn’t cope with the strain of the Grecco case. Yet by all accounts, the matter had been handled properly and the abuser had been tried and awaiting sentencing. Wasn’t the case more or less closed?

It wouldn’t be quite accurate to say that questions about Wingle’s whereabouts are still swirling, at least in the media. After a flurry of reports in the Catholic and mainstream press during the first week of May, the stream of stories stopped as quickly as it began. Whether or not this means authorities have imposed “radio silence” on the matter is hard to say. Neither the CCCB nor the St. Catharines diocese responded to CWR’s requests for comment.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.