On the morning of August 25, 1954, New York Times readers found much of Page One devoted to the news that Brazil’s president Getúlio Vargas – who had dominated his nation’s politics for a quarter of a century even when in short-term eclipse – had killed himself. The man so cryptic that historian Richard Bourne called him “the Sphinx of the Pampas” had sprung one last surprise on his foes.

Nobody accused Vargas of undue charm-offensives. In fact, through his diminutive physique (a mere five feet two inches tall), through his bespectacled face, and through his temperament, he made Gerald Ford look like Justin Bieber. Having achieved absolute office in a 1930 coup, Vargas first used his unbridled strength to smash Brazil’s hitherto influential Communist Party; then, when national fascist elements thought they had a faithful patron in him, he shunted them to the sidelines. Having bestowed upon the Third Reich’s representatives enough honeyed words to suggest that he would join the Axis, he proceeded to hurl the considerable weight of Brazil’s army on the side of the Allies. Brazilian troops saw particularly severe fighting against Mussolini’s Salò Republic. Forced to resign six months after Nazi rule collapsed, Vargas vegetated within the federal senate before returning to the presidential palace in a 1951 election that even his enemies admitted to be fair. But that same army which he had sent to oppose the Führer and the Duce increasingly gave up on him, as inflation approached Weimar Republic levels. Rather than aggravating what had already become a low-level civil war in the streets of Rio (the capital would not move to Brasilia for another six years), Vargas entered one of the palace bedrooms and there committed suicide. The pyjamas which he wore while doing the deed, and the revolver with which he did it, have been on museum display ever since.

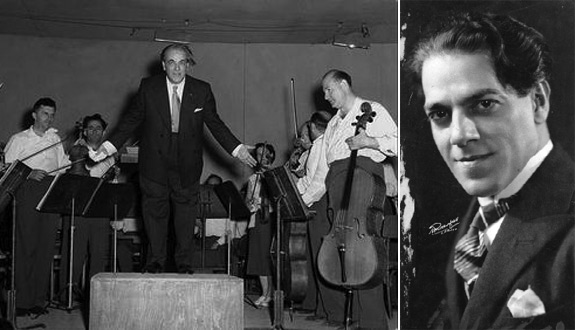

Vargas would not require more than a footnote to cultural history if he had not done the arts a turn so good as to compel our gratitude long after his economic and administrative policies – the policies in which he took the greatest pride – had ceased to interest anyone save specialists. That good turn consisted of supporting Heitor Villa-Lobos, by every possible and many an impossible measure the most musically talented man that South America has ever produced.

***

In 1930 Villa-Lobos, having turned 43, could not forever continue brandishing the flag of enfant-terribilisme. He had eagerly waved that flag for as long as he could, and perhaps longer than was prudent. For example, he rewrote his own résumé with a frantic imaginativeness that might have made Lawrence of Arabia blanch. Like Lawrence, he showed such flair at having blended spin-doctoring with equivocations, half-truths, and periodic outright lies that the resultant heady postmodernist brew frustrated genuine scholarship for decades ahead. If Villa-Lobos’s own accounts are to be believed, he spent part of his pre-1914 youth hobnobbing with cannibals of the Brazilian jungle. It took the 1980s’ researches of biographer Lisa M. Peppercorn to dispel these myths, which Villa-Lobos circulated in order to make himself more novel to European audiences, and which must eventually have alarmed him by the completeness with which they attained official sanction. Let us reflect upon that profound caveat from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

The spectacle of governments using the Servile State’s full weaponry to exalt individual musicians – a spectacle which necessitates demonizing, and occasionally means jailing or murdering, other individual musicians not thus pampered – proved so catastrophic in its outcomes for most of the 20th century (Goebbels, Zhdanov, and Madame Mao are merely the three most notorious names which come to mind) that Villa-Lobos’s creative success is more remarkable than ever. Perhaps it can be in part ascribed to Vargas’s fundamental philistinism. Concert-going, when Vargas could not shirk it, bored him to distraction. What he did have was the instinctive perception that music would be important for his regime; that Villa-Lobos would be important for music; and that whatever kept Villa-Lobos on side was, within reason, worth fostering. Which is why, only two years after taking office, he appointed Villa-Lobos to the role of general manager at Brazil’s SEMA (Superindendéncia de Educaçao Musical e Artistica). This role ensured that – in Dr. Peppercorn’s words – Villa-Lobos, “at the age of 45 … had for the first time a salaried position.”

If Villa-Lobos supped with the Devil, he managed to employ a remarkably long spoon. His pedagogic and other official pieces do not represent him at his most interesting, granted. Still, compared with the near-pornographic love-letters to collective farms and hydroelectric power stations by which Stalin’s tame minstrels avoided the gulag, their virtues are conspicuous. And as for his non-official pieces, they give no indication of a free spirit having sold his soul.

***

That soul, and the nation’s, Villa-Lobos expressed at length through his obviously exotic utterances, best known of these being the series of nine Bachianas Brasileiras: intended, as their title indicates, to strain Bach’s polyphonic techniques through a Lusotropical colander. Here and everywhere else, he always (and for the most part truthfully) denied stealing musical demotics. He went further, maintaining that “I don’t use folklore, I am folklore,” rather as Elgar in England had insisted that “I am folk music.” Even when Villa-Lobos deliberately imitated the sound of Brazil’s street musicians in his 1920s series of 12 Choros (originally 14, though two are lost), his original models suffered “a sea-change / Into something rich and strange,” not to mention a sea-change beyond the imaginings of any Brazilian street musician who had ever previously drawn breath.

During the Hitler war’s final stages, the combination of a looming 60th birthday and Vargas’s departure from national leadership seems to have impressed upon Villa-Lobos the belief that – to quote Dr. Johnson when discussing old age – “it is time to be in earnest.” His creative ethos underwent no violent shift, no Stravinskyan stylistic whiplash. Nor did he reject, as Paul Hindemith (eight years his junior) rejected, his own early productions as mere childish things to be either put away or bowdlerized. When it suited him he could still turn on the enchantment, lovability, and sheer Kodachrome gorgeousness which had dominated such pre-1945 hits as Bachiana Brasileira 5 (an unexpected best-seller for England’s H.M.V. label when Victoria de los Angeles recorded it) and “The Little Train of the Caipira” from Bachiana Brasileira 2. Yet more and more he had other priorities. Another indispensable Villa-Lobos scholar of our time, David P. Appleby, puts it best:

Compositions written late in his life with traditional titles such as symphonies, concertos, and string quartets aroused expectations on the part of critics that these works would also be written in traditional forms. This expectation was one that Villa-Lobos did not want to fulfil, or perhaps could not fulfil.

Among his growing concerns was the sacred. Catholicism-themed compositions, very rare in his catalog before the ascetic, unaccompanied Saint Sebastian Mass of 1937 (he had introduced to Brazilian audiences Palestrina’s Missa Papae Marcelli), abounded thereafter. Thank goodness that a British CD enterprise, Hyperion, has devoted an entire disc to these works. Nobody can claim to understand Villa-Lobos who has not at least sampled them; but those who have discovered them will find them so totally different from the Villa-Lobos of mainstream acceptance that they could readily assume some massive job of misattribution. Such an assumption is untenable. The hermetic, austere, sober-sided Villa-Lobos of this repertoire had subsisted all along. Two pieces in the anthology warrant special notice: the Panis Angelicus of 1950, and the Magnificat of eight years later.

***

Any listener who hopes that Villa-Lobos’s Panis Angelicus might resemble César Franck’s understandably beloved setting of the same text – all ear-worm melody, incense, comfort, and the odor of beeswax – will feel like ripping Hyperion’s CD out of the stereo after the first 20 seconds. Villa-Lobos’s a cappella treatment is shadowy, viscous, and grave, as if belief in transubstantiation had been attained only through enough dark nights of the soul to keep St. John of the Cross laboring double-shifts. In its accents can be discerned something of Messiaen (whose O Sacrum Convivium the Francophile Villa-Lobos could well have examined, although he never demonstrated toward Messiaen the lively enthusiasm he always felt for Darius Milhaud). The result, as in Messiaen, fully accords with the spirit of authentic religion, but accords not at all with the spirit of slushy pietism. Culture-Of-Nice apologists need not apply.

If Panis Angelicus exemplifies Villa-Lobos at his most introverted, then the Magnificat exemplifies him at his most jubilant. Whilst Vargas’s self-removal from the scene did not subject Villa-Lobos to the outright persecution which a new political order’s advent in Moscow or indeed Buenos Aires would have done, it confirmed the widespread idea – among young and strenuously hip Brazilian intellectuals – that the composer had grown truly vieux jeu. To a sympathetic journalist he grumbled: “The country [Brazil] is dominated by mediocrity. Every time a mediocre person dies, five more are born.” Elsewhere he allowed himself a defiance echoing the fox deprived of his grapes: “I regard my works as letters addressed to posterity requiring no answer.” The crowd-loving, crowd-pleasing Villa-Lobos of olden days would have made no such remark.

Yet although Brazil’s post-Vargas privilegentsia despised Villa-Lobos, one figure far more strategically and morally significant than any of them still felt for Villa-Lobos’s musical gifts an exalted respect: Pius XII. In 1958 the Pontiff, his own health declining, commissioned from the Brazilian master a motet to mark the centenary of Lourdes’ apparitions. (He might not have done so had he realized the complexities of Villa-Lobos’s domestic arrangements. Divorce being illegal in Brazil before 1977, the composer had since 1936 maintained a de facto spouse, Arminda Neves d’Almeida, 25 years his junior. No hint of this extended companionship reached curial ears.)

The papal commission’s outcome smacked of nothing which even Villa-Lobos had attempted before. With its thundering drums, with a mezzo-soprano part as solemn and persistently low-pitched as Erda’s contribution to Siegfried, and with its massed brass instruments’ antiphonal motifs suggesting Giovanni Gabrieli, this Magnificat is no hearts-and-flowers setting of Mary’s Canticle, but rather, a fit and proper response to the Catholic Church’s imagery of the Blessed Virgin as militant: “terrible as an army in battle,” a Judith for all times and all races. Pope Pius never lived to hear Villa-Lobos’s swansong, but Villa-Lobos himself – just – did. The Magnificat had its première in Rio’s Teatro Municipal on September 7, 1959. To cite Dr. Peppercorn afresh:

From a box he listened to his own music. When it was all over Villa-Lobos received an unforgettable ovation; it was though, in premonition of his imminent death, the public was paying a final act of homage to its nation’s great composer. Visibly moved, Villa-Lobos, as though delivering a last farewell, waved a feeble, friendly hand.

Thereafter he ceased to appear in public. Ravaged by cancer, he died on November 17.

Clearly, the popular image of Villa-Lobos as check-shirted, gap-toothed, cigar-chomping prankster is way overdue for work under warranty. In 2014 Brazil’s greatest musician stands revealed as a far more versatile – and downright anguished – creator than most of us have ever suspected. Mere clowning? Yes, Villa-Lobos sometimes showed himself guilty as charged. But music-lovers, of all people, should never discount the mythic force of that archetype immortalized by Caruso in Pagliacci: the clown who laughs because he must not weep.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.