Perhaps the most pernicious single delusion to have afflicted musical thought over the last two centuries is what might be called, for want of a comelier description, The Myth of Artistic Inevitability. The central teaching of this myth can be summarized in the slogan, “You can’t keep a good man down.” More specifically, the myth maintains that musical genius, merely by virtue of being musical genius, will always find a mass public; that no agency for evil can ever thwart this process; and that if a particular musician of stature fails to find a mass public, it is fundamentally his own fault.

Belief in the myth presupposes what operated to a limited extent in the centuries before 1914 but manifestly could not be relied on after that date: a European civilization sufficiently filled with noblesse oblige to regard musical genius as worth rewarding, in and of itself. Yet even before 1914 such a civilization was provisional, dependent largely on the caprice of individual patrons’ effort.

Take Wagner, whose monumental self-belief possibly brought him closer than any other great musician has ever come to giving the “inevitable” dogma a fighting chance.But Wagner owed—and he himself knew full well that he owed—his enduring world fame to, above all, a House of Wittelsbach accident. Without King Ludwig II’s patronage, several of Wagner’s masterpieces would have been unperformed and in some instances unwritten. A Wagner without Ludwig II would have occupied something like the same niche in general culture now assigned to, say, Charles-Valentin Alkan: in short, renowned (rightly or wrongly) more for freakishness than for actual lasting merit.

Moreover, the Myth of Artistic Inevitability cannot even begin to explain how so many musical giants were forgotten, for generations on end, once they had died. Monteverdi and Heinrich Schütz in the seventeenth century, Telemann in the eighteenth, Johann Nepomuk Hummel in the nineteenth: all these men—who had substantial, and deserved, reputations in their lifetimes—fell so completely out of favor within a few years of their respective deaths, that it was almost as if they had never breathed.

Still, the main reason the myth is absurd is that it utterly fails to take totalitarian cultures, or even ordinary modern Western leveling,into account. Suppose that there had emerged in the twentieth entury a composer who combined the gifts of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven in his own person. Those gifts, far from guaranteeing him popular acclaim and a berth in Grove’s, would not have done him a blind bit of good if he had been stuck amid the Holodomor, or amid Khmer Rouge Cambodia, or amid Maoist China’s Cultural Revolution, or (if he had possessed Jewish ancestors) amid Nazi-occupied Poland. Indeed, his exceptional abilities would have increased the likelihood of his being hunted down like a rat.

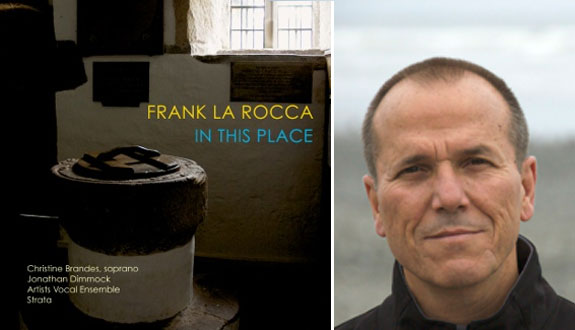

All this serves as a prelude to noting several facts: first, that there flourishes in America a composer named Frank La Rocca; second, that his creative talent for religious music is remarkable; third, that one can have been a professional musician—indeed a professional church musician—for decades without having encountered his name, let alone his output; and fourth, that those in that ignoramus category had included myself, until his CD In This Place, was recently brought to my attention—and by a non-musician! According to the Myth of Artistic Inevitability, such neglect could never have happened. I would, for certain, have discovered La Rocca’s work in the quotidian course of events; every decent-sized musical reference book would have alerted me to that work; it would be needless to accord him wider fame by writing the present article; and pigs would fly.

+++

A good case can be mounted for listening to all unfamiliar music, as it were, “blindfolded”. In other words, for judging it entirely upon what the ear apprehends, with no biographical or other data to affect one’s pleasure or distaste. Accordingly, before seeking any information about La Rocca’s career, I began playing the CD, and I concentrated exclusively on what I heard.

What I heard managed to reveal, within the first 60 seconds of the initial track—O Magnum Mysterium, to words best known through Tomas Luis de Victoria’s version—that something uncommonly interesting had unfolded. Stylistically the music (most of it choral, though it included a piano solo called Meditation) bore traces of Arvo Pärt, yet was conspicuously not by Pärt himself. Likewise, it bore traces of the late Sir John Tavener, yet just as conspicuously did not emanate from Tavener’s pen. It showed a composer comfortable not only with the setting of Latin words but with large musical structures, a fact that in itself separated him from most of the minimalists whom his writing might otherwise have suggested.

Equally unmistakably, it breathed the atmosphere of mystical devotion, Messiaen being occasionally implied in the piled-up vocal harmonies and the suggestion that “the still point of the turning world” had been intuitively (rather than logically) arrived at. But it could not be classified as fake-Messiaen either. One thing was sure: it defied switching off, whether literally through pressing the stereo’s relevant button, or metaphorically through letting the attention drift elsewhere.

At this point, and not before, I called the Internet to my didactic aid. From various websites, including La Rocca’s own site, I learned that La Rocca, born in New Jersey 63 years ago, had acquired his bachelor’s degree in music from Yale (1973) and his doctorate in music from Berkeley (1981). Among his teachers he numbered Andrew Imbrie and John Mauceri, neither of whom would have the slightest inclination to waste time and effort on a mere cashed-up dilettante. A former Calvinist, La Rocca converted somewhere along the line to Catholicism, and since then has devoted a remarkable amount of his energy to the production of choral music, most of it in Latin. This music has been heard not solely in the United States, but also in Brazil, Portugal, Britain, France, Germany, and the Czech Republic.

+++

It is among the most difficult of all pedagogical tasks to depict, through mere words, musical originality. This musical originality La Rocca has somehow acquired, without the smallest detectable straining after it. Especially notable in this connection is this album’s Credo, a text that often gives second-rate composers trouble, because of its sheer length and its limited number of opportunities for word-painting. No such problems perturb La Rocca, who has treated it with a master craftsman’s hand. His other Latin settings on this disc—they include Miserere, Expectavi Dominum, and O Sacrum Convivium—are equally free from either dullness or archeologism (which is really no more than dullness’s arrogant elder brother).

A few small but nagging worries do arise. Given La Rocca’s rare ability to extract, as it were, the most luscious harmonic juices from slow-moving unaccompanied material, one does—albeit with reluctance—hanker, on occasion, after something more overtly agitated: if not merriment, then at least the occasional allegro or indeed allegretto marking. And after protracted exposure to La Rocca’s a cappella inspiration, the fear arises that the composer might be instrument-averse.

There lurks a certain type of foolish male Catholic who, in a perpetual snit at modern Rome, battens with reckless enthusiasm upon Constantinople. Such a Catholic can be recognized by his detestation of instruments in general and of the organ in particular. Happily, La Rocca runs no danger of affording such an iconoclast comfort. Not only does the present album include a mournful violin-clarinet-piano trio (the title track), but an online search quickly unearthed a live performance of La Rocca’s 2005 Resurrection Prelude, which has all the gravity and power of his choir-only compositions, though this time with brass, organ and percussion added to the mix. Its allusions to Mahler’s Second Symphony and to Richard Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration have no hint of“look how erudite I am” postmodernist self-consciousness. Instead, phrases from the older works become unobtrusive additions to the fabric of the new one.

How much of a commercial proposition La Rocca’s oeuvre is, I have not the slightest idea. The fact that no less an imprint than Boosey & Hawkes has him in its catalog indicates that he must be enjoying respectable sales. Nevertheless, I can imagine the squawks of outrage with which most Australian Catholic parish choirs would greet his music’s challenges. (There are exceptions among such choirs, but they are painfully scarce.) Notwithstanding La Rocca’s freedom from superfluous detail, not a single choral item on this CD would be easy for massed singers to get right. Nor is Veni Sancte Spiritus—for solo soprano with the backing of clarinet and strings—free from traps: its vocal line, becalmed for the most part, demands an unexpected high A near the finish. (The instrumental writing, here and elsewhere, sounds more technically straightforward.)

Maybe, at any rate outside La Rocca’s homeland, we must look foremost to cathedral choristers for adequate renditions of his vocal pieces. That the effort involved in these renditions would pay singers back with abundant interest, is demonstrated many a time. Making La Rocca’s musical acquaintance has been, without question, an artistic highlight for me of A.D. 2014.

[Editor’s note: The original version of this article stated that Dr. La Rocca was “originally Calvinist”; that has been changed to more clearly state that he was once was Calvinist, but is now Catholic.]

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.