On April 14, 1927, the following passage appeared in the newspaper Il Mattino:

On few occasions has Naples witnessed a spectacle so impressive in its boundless sorrow, which goes to show how much affection, esteem and admiration had been won by the man who was able to turn his profession into a very noble apostolate…with the aid of his teaching, to lavish his unparalleled goodness on all who were suffering, and who was able to demonstrate how, marvellously, religion and science can be reconciled.

Those were the words of a secular newspaper about a man who belonged very much to this world by virtue of how he lived and the profession he practiced, but whose life also spoke of a very different world. The life of Giuseppe Moscati was, in many ways, a fusion of the secular and the spiritual, of the professional scientist and the believer, of the earthly and of that which belongs to another realm. In his life, however, there was no dichotomy to be found; it was of a whole that, eventually, grew into holiness. The crowds that bid Giuseppe Moscati farewell that April day in 1927 recognised this quality; soon the wider world would come to recognize it too.

Many in the English-speaking world, I suspect, will not have heard of Moscati. The publication by Ignatius Press of Saint Giuseppe Moscati: Doctor of the Poor by Antonio Tripodoro will help introduce him to a wider, English-speaking audience. The book is an English translation of the original Italian text published in 2004. It is a relatively short book (under 200 pages), but it tells its story well, in an understated and yet inspiring fashion, with just the right amount of fact, detail, and anecdote to allow for the saint to emerge from its pages.

In many respects, the life of the man who was to become a saint is unremarkable. It could be summed up in a few lines: he was devoted to his family and his friends, he was an excellent practitioner of his chosen profession of medicine, and he lived and died devoutly. One feels that that is where the subject of the biography would have preferred matters to rest. All his life, no matter how influential or important in the eyes of the world he became, he was nothing if not self-effacing—one of the qualities that one notices in the biographies of saints. They shun the limelight; their eyes are upon another light, one the world has difficulty seeing. So it was with Moscati.

That said, saints rarely live alone. Many, like Giuseppe Moscati, live in the thick of the world’s hustle and bustle, with all its problems and challenges, hopes and dreams, cruelty and kindness. This was even more pronounced in Moscati’s life given his calling. As a doctor, he was constantly confronted with the mystery of illness, the many ailments of various hues, and, ultimately, the great mystery of death. Very early in his vocation, Moscati achieved the synthesis of the hope that stemmed from his faith and the acceptance of hopelessness in the face of some medical diagnosis. He knew the answer lay in the Cross. In the hospital mortuary where sometimes he worked he had a Crucifix attached to one of the walls—reminding him and others present that the way of all flesh must pass through death but that only one Death had satisfactorily answered that mystery.

Of course Moscati’s help to his patients was practical. He was not a good doctor; he was, by all accounts, a brilliant doctor, truly gifted in his chosen field. His renown passed well beyond the bounds of Naples. He could have been famous the length and breadth of Italy, but he chose not to be. Furthermore, his expertise could have made him a wealthy man. Instead, he renounced all personal gain, choosing instead to work mainly among the poor for only token sums. Stories abound in the book of how he would find ways to take as little as possible for his services, often accepting a paltry recompense simply so as not to offend those offering it. In any event, it seems that the little he earned he gave away, quietly and often unobserved, to the city’s poor. How modestly he had lived was only really understood after his death. Nevertheless, he felt he was a fortunate man. He loved his calling; and his work was nothing less than a joyful affirmation of his part in a greater plan.

As one might expect, Moscati was always devout. From childhood, he had been brought up in a Catholic family and was never to deviate from his faith. His adult life was one of work and prayer, of charity and devotion to the sacraments, especially to daily Mass, and living the present moment in the gaze of eternity. Nevertheless, there was nothing overly pious or off-putting about him. He was a professional man who went about his business the same way his peers did, but with one difference; there was something noticed and later brought out in the testimony of those with whom he came in contact. They speak of an intangible sense of goodness about him; all those who came across his path, whether a patient or fellow medical professional, were touched in some way by this goodness. In order to really to know someone, you must ask, it is said, those closest to that person, those who live cheek by jowl with him or her, whether at work or at home. The testimony of this book suggests that those who observed Moscati daily and at close quarters were not only impressed by the mind of the doctor they met, but were also moved by the holiness of the soul they encountered.

It was not all work, however; Moscati led a balanced life. A cultured man, he had an interest in the natural world, in architecture and art. In the summer of 1923, he traveled abroad, notably to Paris and London. In the latter city, the book recounts how he visited the National Gallery. There, amongst many artistic masterpieces, he would later write of being struck by Da Vinci’s ‘The Virgin of the Rocks…many paintings by Rubens and Van Dyck: the Flemish and Italian painters are still joy and the glory of picture galleries throughout the world! One marvelous English painter (or rather American…) is Sargent. Portraits with a suggestive power.’ When next I visit that venerable institution it shall feel changed knowing that a canonised Saint walked in those same rooms. It is good to be reminded of the ordinariness of sanctity.

Moscati was born in 1880 and died at the relatively young age of 47. As an adult he had felt drawn to and embraced celibacy, thereby being more available to his patients. It was not simply for professional reasons though; he felt celibacy to be part of his divine calling. Similarly, his frugal lifestyle was not the result of eccentricity; it too was an integral part of his calling, as he saw it, to live out his Christian vocation—to be in the world but not of it. Needless to say, his professional eminence was lightly worn with his students and colleagues. On occasion, he would gladly state where any true ‘eminence’ really lay. He was, in short, a good man, a doctor well-loved by the people of Naples, a valued colleague and teacher in the medical fraternity of that city, but, in the end, he was, and this is the most important part, a holy man.

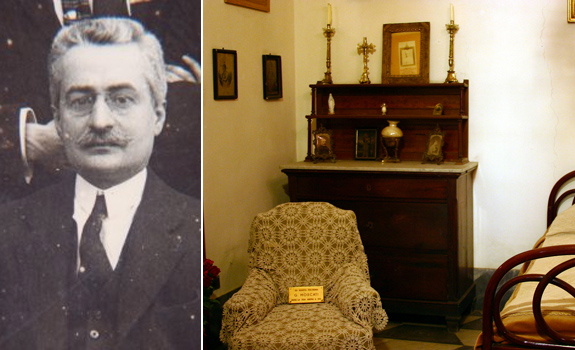

He died as he lived, quietly. He passed away sitting in a chair with his arms crossed. The only thing of note was that it was Holy Week. He was laid to rest on Holy Thursday, a fitting day given his devotion to the Blessed Sacrament. It was also apt from another perspective. All his life he had seen in the broken bodies of those he served another Body; as he was to say to anyone who asked why he served the sick, it was in their faces that he saw the Face of Christ. The words spoken at the Last Supper—‘This is my Body’—were, in the life of Giuseppe Moscati, translated into a practical mysticism that pervaded the consulting rooms and hospital wards through which he moved. For him, there was no disjuncture between what took place each day at the early morning Mass he attended and later that same day in his medical practice, between the man attending to the needs of the body and the one attending to those of the soul.

On 25 October 1987, Pope John Paul II canonized Giuseppe Moscati. It was fitting that as this layman was being raised to the heavenly altars, the Seventh General Assembly of the Synod of the Bishops was taking place at Rome. Its deliberations were on the theme of: The Vocation and Mission of the Lay Faithful in the Church and in the World. In this new saint, the Church had just been given an outstanding witness to both.

(This review was originally published on February 17, 2016, and is reposted to mark the feast day of St. Joseph Moscati,)

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.