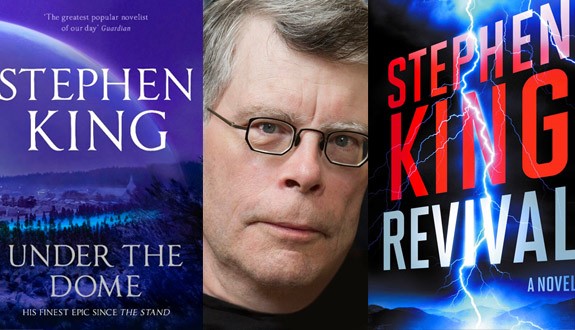

With the recent release of Revival, best-selling author Stephen King upholds his commitment to terrifying us by invoking the supernatural while telling stories of compelling characters and horrific events. Revival’s fallen clergyman joins a long list of lapsed Christians in King’s novels, and this newest release may move many Christians to conclude that King has escalated an attack on Christianity. But they would be wrong, we would like to suggest. While King introduces a flawed religious figure in the Rev. Charles Jacobs—a minister whose faith in God has been replaced with an obsession with science and technology—King also reminds readers what happens when humans try to become “like God.”

The cunning Jacobs is described by King as having a voice that is “soft and silky…the voice of a coaxing devil,” and he promises his protégé that he can “unlock the door that leads into the Kingdom of Death.” The consequences are predictable, because as Christians and King know, no mortal should ever try to unlock such a door. In this way, Revival, like many of King’s best novels, is really a morality tale—a tale of what he has called “dark Christianity.”

King is viewed with skepticism by many Christians because he seems to denigrate Christians whenever he can. Last summer, King drew the ire of believers when, in reference to the thousands of undocumented children from South America seeking asylum in the US, he posted on Twitter that it is “much easier to be a Christian when the little children aren’t in your back yard,” ignoring the fact that Christian organizations were the first to respond to the humanitarian crisis at the border. Some Christians turned to their own Twitter accounts to charge that King’s books “celebrated evil”; one tweeted that King’s books were demonic—and that the author was being “used by Satan to bring about the destruction of souls.”

But King’s representation of Christians in his novels is much more complex than that. While King often disparages organized religion in his stories of horror, his writing has never celebrated evil. In fact, a close reading of his novels reveals strong—and sometimes explicit—biblical themes and affirmations. In some important ways, King provides the last bastion of biblical morality in popular fiction—the final stronghold against a secular society that has dismissed Satan and his evil minions.

Our society’s insatiable hunger for horror has helped King remain at the top of the best-seller lists for decades. Film adaptations of King’s novels are among the highest grossing at the box office, and one of last season’s most popular television series, Under the Dome, is an adaptation of King’s novel of the same name. Portraying a small New England town that is sealed off from the world by an enormous, impermeable dome that inexplicably appears out of nowhere, Under the Dome exposes the weaknesses and the fears of the town’s residents as they contend with a post-apocalyptic world that at first seems filled with evil—and left behind by God.

Uncertainty about our own “end times” is a theme in many of King’s novels. But, for King, we inhabit a world that the benevolent God seems to have abandoned—replaced by the wrathful God of the Old Testament. For King, God’s actions may seem cruel and unreasonable, and His aims unknowable. Christian readers can identify with these themes, as they know that bad things often happen to good people, often for no reason that they can understand. King uses these occasions to demand that we reconcile ourselves to our mortality—reminding us that we are all moving toward death. But King also reminds us that we are not alone in this journey—God’s power is unmatched. And, although the demons may win a few of the battles in his books and in our lives, King offers a reassurance that the demons will never win the war; they don’t pose a real threat to the power of God himself.

Our attraction to the macabre in our popular culture is intensifying at a time when fewer people than ever claim to believe in the devil. Americans are much more likely to believe in God and an eternal reward in heaven than to believe in the devil and the possibility of an eternal punishment in hell. A 2013 Harris poll reveals that 74 percent of all Americans believe in God, but only 58 percent believe that the devil exists. In the UK, the BBC reported in 2014 that while one third of the population claims to attend Church of England services, only 29 percent of the population believe in the devil. Responding to the decline in belief in the existence of the devil in the UK, the Church of England recently voted to delete all mention of Satan from their baptismal rites. How can godparents renounce an entity in whom they no longer believe?

While belief in the devil declines, interest in horror stories about the devil—and the evil within—is stronger than ever. King understands our uncertainty and our fears. He reminds us of how little we know and understand. In Danse Macbre, King’s 1981 non-fiction analysis of the role that the horror story plays in our everyday lives, he suggests that all tales of horror can be divided into two groups: those in which the horror results from an act of free and conscious will—a conscious decision to do evil—and those in which the horror is predestinate, coming from outside like a stroke of lightning. For Christians, there is always a choice between good and evil; King acknowledges this reality:

The stories of horror which are psychological—those which explore the terrain of the human heart—almost always revolve around the freewill concept: “inside evil” if you will, the sort we have no right laying off on God the Father. This is Victor Frankenstein creating a living being out of spare parts to satisfy his own hubris, and then compounding his sin by refusing to take the responsibility for what he has done. It is Dr. Henry Jekyll, who creates Mr. Hyde essentially out of Victorian hypocrisy—he wants to be able to carouse and party-down without anyone, even the lowliest Whitechapel drab, knowing that he is anything but saintly Dr. Jekyll whose feet are “ever treading the upward path.”

King suggests that horror is “innately conservative, even reactionary.” He believes that we are attracted to horror because we need to reestablish our feelings of essential normality. It is likely that readers—including many Christian readers—are drawn to King’s tales of horror because he is among the last popular fiction writers willing to acknowledge that evil exists, and that even in our therapeutic society, which has redefined badness into illness, evil results from an act of free and conscious will. Christians have always understood that.

While evil is pervasive in his novels, King knows that it is impossible to write plausible horror—a world filled with evil—without a corresponding sense of the good. This is why nonbelievers often find King’s horror objectionable; some of the strongest critiques of his writings focus on the books in which the existence of God is made explicit. King told an interviewer that he received his harshest criticism from readers of Desperation, a novel that he called a “very Christian novel.” Desperation is about a small band of survivors of a mass killing by an unknown evil force in a Nevada mining town. The central character is David Carver, a 12-year-old believer who seems to have been called by God to lead others to the light. David’s conversion was coupled with the miraculous healing of a friend through David’s intercessory prayers, but he seems to pay a high price for his answered prayers when his entire family is destroyed. Like the biblical Job, David is “required to live” when death would have been more welcome. Like Job, David cries out, “He can’t take them all and leave me.”

King reminds his readers that God may appear to be cruel. Yet secular critics are offended by the explicit citing of the God of Abraham in many of King’s works. King has responded to these criticisms by asking why readers are able to accept the most fantastic stories of monsters, zombies, vampires, and demons, yet are offended by stories featuring God. As a rapid and militant secularization has consumed Western culture, the traditional faith that once provided a deep understanding of good and evil and the pivotal struggle between the two is no longer a part of the cultural landscape.

The popularity of horror is likely explained by some unfulfilled need. One of the most important attributes of the horror genre as envisioned by King is the relationship between the subtle struggle against internal evil and the more overt struggle against external evil. While the external struggle often drives the narrative, there is often a simultaneous struggle within the hero and his own flawed character.

Stephen King’s heroes are often flawed—struggling with their own internal weaknesses. Dale “Barbie” Barbara, the hero of Under the Dome, and Johnny Marinville, the reluctant hero of Desperation, must both overcome personal demons from their military days. Both characters harbor guilt for horrific acts that drove them to flee rather than confront their problems—until they are given no choice but to stand up to evil in hopes of some form of redemption. Similarly, in King’s 2013 book Doctor Sleep, an adult Danny Torrance, the boy from King’s earlier novel The Shining, must redeem himself from his alcoholic past—which included the death of a drug-addicted young woman and her infant son due to his negligence—by helping save another young woman from evil.

“A child shall lead them”

In a posting on CNN’s Belief Blog a few years ago, John Blake identified three biblical themes that he believes characterize King’s writing. Blake pointed out that King’s stories often focus on children with supernatural gifts and identified “A child shall lead them” as one of King’s most important biblical themes, along with the “cruelty of God” and “God chose the weak to shame the strong.” In reference to this last theme, Blake points out that King often chooses the least likely characters in his stories to triumph over evil—to the embarrassment of the strongest characters. This theme is most explicit in his 1996 book Desperation, which introduces 12-year-old David Carver, a boy who prays and receives explicit messages from God on how to proceed. David always does what God tells him to do, and as a kind of evangelist, he actually brings others—even those who have been dead to Christ, like Marinville—back to belief in the power of God. In The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, a little girl receives divine intervention by means of her favorite Red Sox baseball player. The child in The Shining channels supernatural powers from God, and in Doctor Sleep, a little girl uses supernatural powers to overcome the evil RV-driving monsters who prey on the young. In Revival, a young, innocent, and faithful Jamie Morton meets the then-faithful Rev. Jacobs and is shaped by him. When Rev. Jacobs loses his faith, Jamie’s faith is shaken, but the reader can see that God will never abandon us—unless we abandon him.

In addition to children, King turns flawed individuals—sometimes, the weakest character in the book—into the real heroes of their stories. In Mr. Mercedes, King chooses an overweight retired detective, who has become a suicidal recluse, to be the hero of the story. At the start of the novel, we are told that the detective spends his days watching daytime television with his service revolver on an adjacent table, trying to decide whether to put the gun into his mouth and pull the trigger. But we realize later that he is just the man to confront the evil force that has emerged in his town.

There are other biblical themes woven throughout King’s work. He has taken to heart Proverbs 16:5—“the sin of pride will not go unpunished.” Troubled by prideful people, King finds ways to humble them. He also makes it clear that “the gates of hell will not prevail.” For King, evil characters may wreak havoc and cause serious destruction. But they are never portrayed as attractive or glamorous. And they never win in the end. This is especially true in Revival, in which the initially handsome and charming Rev. Jacobs becomes increasingly physically unattractive as he pursues his quest to be “like God.”

King portrays complex heroes who fight their own demons as they battle the external horrors. For example, Father Callahan, who plays a pivotal role in Salem’s Lot and later reemerges in the Dark Tower series, begins the narrative as an alcoholic priest who doubts his own faith. As he joins the battle against a group of vampires, there is a clear strengthening of his moral character. Yet in the face of evil, Father Callahan ultimately loses faith and appears to concede. But in The Wolves of the Calla, Father Callahan rejoins the fight against the evil vampires, and by the last book in the series, The Dark Tower, he appears to have regained his faith. Similarly, Danny Torrance in Doctor Sleep wastes decades of his life before his redemption.

It is true that King seems to have become increasingly ambivalent about the value of organized religion, and he often creates clergymen who are hopelessly lost. Populating his stories with weak alcoholics like Father Callahan or Rev. Martin, the minister in Desperation, King shows an opposition to organized religion that is palpable. In Revival, Rev. Jacobs has replaced his faith in God with an obsession with science and the power of electricity. In Under the Dome, one of the local ministers runs a methamphetamine lab behind his church. Another, the Rev. Piper Libby, has lost her faith and prays to “the great nobody.” Abandoned by organized religion, the citizens have no one else to help them cope with the oppressive dome that has settled over their town. Similarly, in the film adaptation of The Dead Zone, King’s 1997 novel, the primary antagonist, Greg Stillson, is a Bible-salesman-turned-politician who threatens an apocalyptic end to America. Stillson is brought to prominence by the hypocritical, politically conservative Rev. Gene Purday, who forms a Moral Majority-type organization and employs his Faith Heritage Chapel for a variety of nefarious purposes.

Despite creating a clergy that is fallen and unrepentant, King comprehends the power of God—and the power of prayer. For King, even those who have seemingly lost all hope can find redemption when they ask God for help. On the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the publication of The Stand, a book that King once called a tale of “dark Christianity,” the author told an interviewer that the book was his attempt to “give God his due…I wanted to explore what it means to be able to rise above adversity by faith, because it’s something most of us do every day.”

For King, there is no question that evil exists, that demons are real and must be defeated before they are allowed to defeat us. Perhaps this is the greatest gift King gives to his readers—to remind us that evil will never triumph if we are able to recognize it and refuse to invite it into our lives, remaining willing to look to God to help dispel the demons.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.