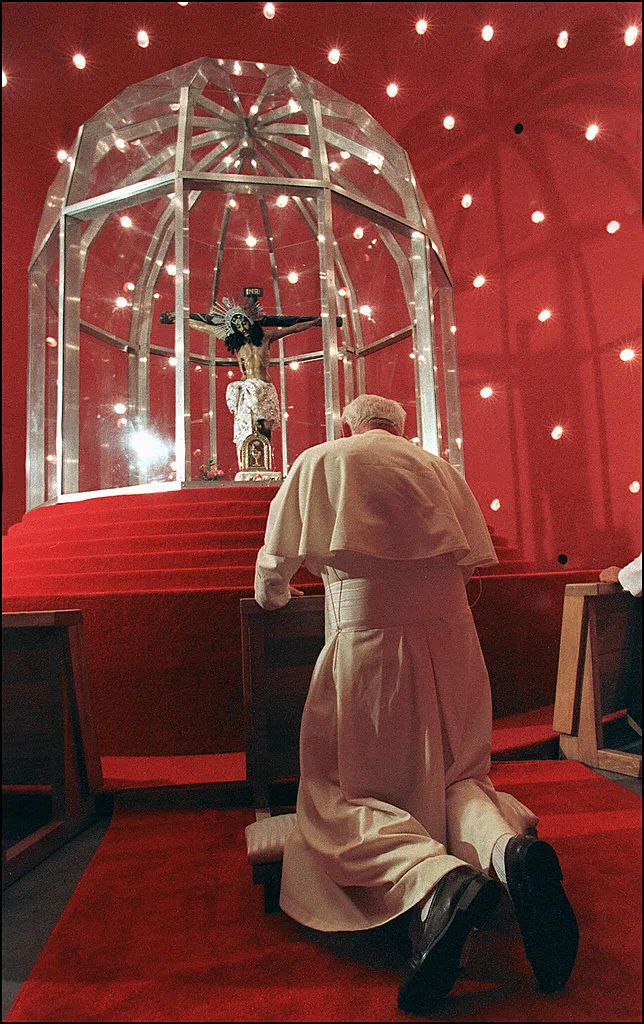

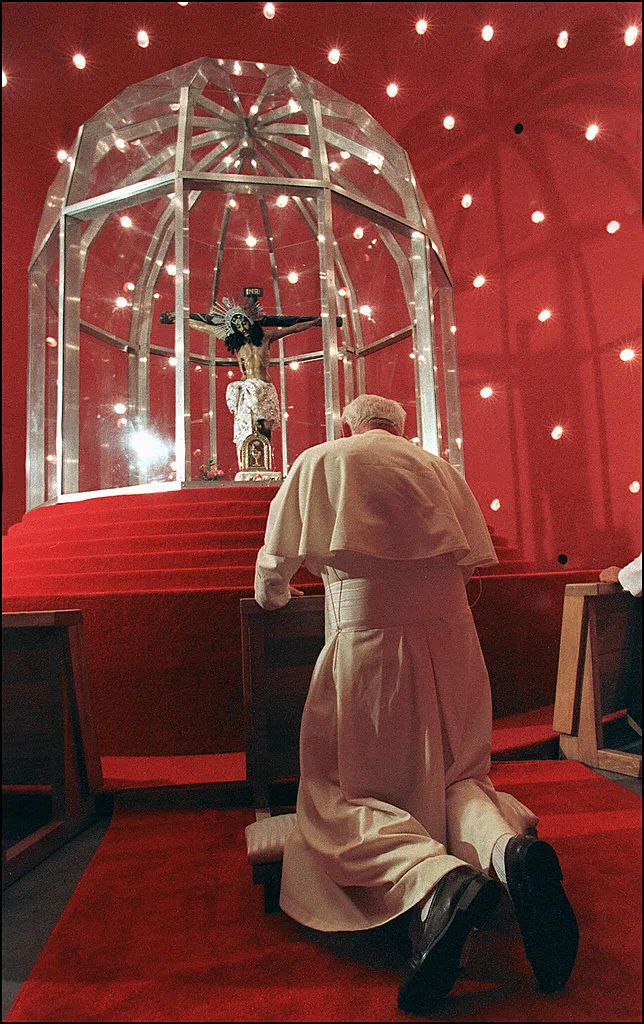

Pope John Paul II prays in Managua’s cathedral before ending his visit to Nicaragua on Feb. 7, 1996. / Photo by RODRIGO ARANGUA/AFP via Getty Images

Pope John Paul II prays in Managua’s cathedral before ending his visit to Nicaragua on Feb. 7, 1996. / Photo by RODRIGO ARANGUA/AFP via Getty Images

Denver Newsroom, Aug 27, 2022 / 04:00 am (CNA).

On Feb. 7, 1996, during his second trip to Nicaragua, then Pope John Paul II referred to the visit he made in 1983 as a “great dark night.”

“I remember the celebration of 13 years ago; it took place in darkness, on a great dark night,” said the pilgrim pope at the Mass he celebrated in Managua with the country’s families.

During the 1996 Mass, the Polish pope elevated the church of the Immaculate Conception of El Viejo to the rank of basilica, where Nicaraguans venerate “the Most Pure Immaculate Conception” so that “she may always be Mary of Nicaragua.”

In the Central American country — and as was heard recently in Managua — the phrase “Mary is from Nicaragua and Nicaragua belongs to Mary” is common, due to the great love Catholics there have for the Mother of God, an affection that does not bow down to the persecution of the dictatorship.

The dark night

The Alitalia plane that took John Paul II to Nicaragua landed at 9:15 a.m. local time on March 4, 1983.

In Managua, the authorities of the Sandinista Governing Junta were waiting for the pope, including the junta coordinator, Daniel Ortega, who with his wife, Rosario Murillo, now lead the current Nicaraguan dictatorship.

The Polish pope arrived in a country that was on the verge of a civil war.

According to Nicaragua Investiga online news, there was a banner at the airport that said “Welcome to free Nicaragua thanks to God and the revolution.” In this setting, Ortega delivered a speech in support of the Sandinista regime.

John Paul II greeted the other authorities who were waiting for him, as well as Ernesto Cardenal, a priest and Marxist liberation theology activist who was holding public office as the regime’s minister of culture, something incompatible with the ministry of Catholic priests.

“When he came over to where I was, I did what I had planned to do in this case: take off my beret and kneel down to kiss his ring. He didn’t let me kiss it, and waving his finger as if it were a cane, he told me in a reproachful tone: You must regularize your situation. Since I didn’t answer anything, he repeated it again,” Cardenal recounted in his book “The Lost Revolution.”

In his opening address, John Paul II said that he was arriving in Nicaragua “in the name of the One who gave his life for love for the liberation and redemption of all men. I would like to make my contribution so that the suffering of innocent peoples of this area of the world ceases; so that the bloody conflicts, hatred, and sterile accusations end, leaving space for genuine dialogue.”

In addition to Cardenal, other priests were also part of the government: his brother Fernando worked with the Sandinista Youth, Miguel d’Escoto was the foreign minister, and Edgar Parrales was a diplomat.

Hugo Torres, then head of the political leadership of the Nicaraguan Army in those years, recalled that there was heavy security to protect the pope, also because one day before the pope’s arrival, 17 young Sandinistas were killed by the “Contras,” the counterrevolutionary group financed by the United States that engaged in a civil war with the Sandinistas for a decade.

John Paul II then went by helicopter to León, where he said a few brief words to the faithful present before returning to Managua.

Disruptions at Mass and the pope’s response

At the beginning of the Mass and before hundreds of thousands of people present, the then archbishop of Managua, Miguel Obando Bravo, greeted John Paul II and compared his visit to one made by Pope John XXIII to a prison in Rome.

During John Paul II’s homily, in addition to the faithful cheering the pope and Obando — who would later become a cardinal — groups of Sandinistas also shouted slogans in favor of their revolution.

“Between Christianity and revolution there is no contradiction,” “Power to the people,” “The people united will never be defeated,” “The people’s Church,” and “We want peace” were some of the slogans they shouted.

The shouting angered the pope, who asked for silence more than once and finally told them: “Silence. The Church is the first to want peace.”

According to the Spanish newspaper El País, John Paul II also went off script and said: “Beware of false prophets. They present themselves in sheep’s clothing, but inside they are ferocious wolves.”

At the end of the Mass, the Sandinistas played their anthem, after which the pope was taken to the airport, where he was again received by the current dictator Ortega, who reproached him for leaving without praying for the 17 youths killed by the Contras and justified the shouting by the Sandinistas during the Mass.

“The pope didn’t do it (pray for the dead) because I think he thought that any word he said in that regard could be interpreted as a word of support for the revolution,” Hugo Torres recalled.

In his farewell speech, John Paul II did not respond to Ortega’s attacks but rather expressed his thanks for the welcome he received and encouraged the Christians.

“In fidelity to your faith and to the Church, I bless you from my heart — especially the elderly, children, the sick, and those who suffer — and I assure you of my enduring prayer to the Lord, so that he may help you at all times,” the pilgrim pope said.

“God bless this Church. God assist and protect Nicaragua! So be it,” he concluded.

This story was first published by ACI Prensa, CNA’s Spanish-language news partner. It has been translated and adapted by CNA.

[…]